A national or racial culture exists when the works (art, letters) of that nation do not and do not need to ask favours because they have been produced by a member of that particular nation or race.

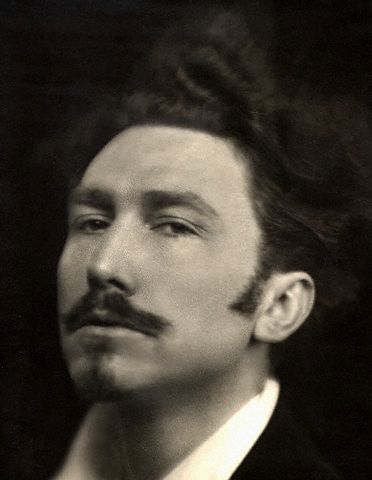

– Ezra Pound.1

Ezra Pound 1918, USA. Image © E.O. Hoppé/CORBIS

During a recent confrontation on a university campus, I had cause to remind a young chap of the importance of identity and its transmission through simple, organic devices such as folktales. In an effort to show him that, in his rush to defend the identity of others, he had abandoned his own identity (which also happened to be mine). I posed the question to him; “What stories, songs, tales, dramas even lullabies will you share with your children in order to convey to them their identity and their values?”

Clearly he had never contemplated the question, and I had caused the poor lad to seriously question his notion of culture as a ‘social construct’ (What on earth does that phrase actually mean? I don’t think he had an answer for that either). Observers of the conversation found his situation quite pitiful, but cautiously so, as they asked themselves the same question in their head. At least they saw the significance of it.

This brings me to the point of the current discussion – the importance of the instruction of Tradition. The importance is particularly heightened when one has children. Any self-respecting traditionalist is suspicious of state education, and may even regard it as part of the apparatus for undermining Traditionalist parenting. If you do take it upon yourself to be a Traditionalist parent, one of the first things that you need to do, is to orient your children with a moral compass.2

Most cultures throughout the ages have been cognisant of this need (before such responsibility was abrogated to the state) and they created a number of cultural devices to instill the values of their society in the minds of children. Along with the values, came a sense of identity and origin so that the child had a sense of place in time and space. With this came a sense of confidence and belonging. The wisdom of our ancestors informs us that the modern, sentimental nonsense of “all a child needs is love” is indeed bunkum; what a child craves is a sense of comfort and normality. For the needle of the moral compass to ‘point’ it needs to be anchored at one end.

This notion is shunned by Zinga and Zola (‘partners’) in their inner-city terrace house because it deeply disturbs their self-indulgent worldview. In their desire to legitimise their deviance from the norm, a child represents a political statement as much as the answer to a muffled biological call. The child is also likely to be designed to match the curtains and lounge room cushions – after all, isn’t breeding the pinnacle of accessorising? It is not in the interest of such ‘progressives’ to see traditions being forged among the children of the majority, as this may lead to the undoing of the social transformation and anaesthetising executed to date by all the parasites clinging to the hull of the H.M.S. ‘Frankfurt School’.

In modern Anglo-Saxon society, the inner-city intellectual class seems to have purged the average person of any recognition of the need for transmission of tradition. The bedtime stories of their own childhood have been displaced by sanitised ‘educational’ tools, politically correct memes, utilitarian devices and just plain consumerism such as computer games. The Frankfurt School march through the institutions has a firm grip on education, and the grasp is so broad there has been enough room for a goulish, ideological thumb to be firmly pressed into the carotid artery of education in the home. As the folk band Show of Hands sings in their cautionary tale ‘Roots’: “Without our stories and our songs / How will we know where we come from?” Indeed – make the young disconnected from their own identity and they become more pliable to ideological projects that begin at birth (and would begin in utero, but for the risk that such might be a de facto recognition of life in the womb).

The Traditionalist needs to respond to this situation with determination and self-awareness. It is much more critical than first appears. Unlike our forebears, the Traditionalist caught in modern times is likely to be forced into a ‘dual income’ home economy. The pace of the modern world, in spite of its devices of convenience, means that the time to spend with your children sharing in cultural delights has to be found and kept. Parenting has always been a time poor exercise, but the ‘natural space’ allocated to folkish matters has steadily been displaced (This phenomenon becomes very apparent when one goes camping or has a spell in the country – the television and passive entertainment options dry up very quickly and the ways and values of the old world come to the fore).

The Traditionalist needs to respond to this situation with determination and self-awareness. It is much more critical than first appears. Unlike our forebears, the Traditionalist caught in modern times is likely to be forced into a ‘dual income’ home economy. The pace of the modern world, in spite of its devices of convenience, means that the time to spend with your children sharing in cultural delights has to be found and kept. Parenting has always been a time poor exercise, but the ‘natural space’ allocated to folkish matters has steadily been displaced (This phenomenon becomes very apparent when one goes camping or has a spell in the country – the television and passive entertainment options dry up very quickly and the ways and values of the old world come to the fore).

The first thing that Traditionalists, who happen to be Anglo-Saxon (and in the writer’s estimation, Anglo-Saxon traditionalists are in a dire situation compared with most other cultures they encounter), need to do is to identify and preserve their own cultural stories: Beowulf, Sir Gwain and the Green Knight, The Canterbury Tales, Grimm’s Fairy Tales, to name but a few. Soon it will become evident to the parent that the first part of the exercise is to re-acquaint, or even discover for the first time, these cultural artefacts for themselves. You will be surprised about exactly how much of your own heritage you are ignorant. This is a most beneficial exercise. The mutual learning process is both bonding and an investment for the future. Children learn by the parent’s example, as they see the parent being prepared to learn as well as teach. This prepares them in turn to carry on the process in the following generation.

Secondly, the sharing of such stories has to become a family exercise. The whole family needs to gather around an old book and share the experience in a more ‘folkish’ way, such that the experience isn’t some sort of utilitarian educational function. Rather it becomes akin to a deep familial experience. In this way, the lessons learned become so deep seeded, that they almost act as a prophylactic against the attempts to impose ideology through the institutions.

As the parent, one finds one’s self becoming eager to learn more about one’s own traditions. Children are prone to asking questions, and they expect answers. It is also important not to patronise children – just because an answer is simplified, it doesn’t mean that it shouldn’t be accurate (after all, the Great Wall of China wasn’t built “to keep the rabbits out”). Children may not comprehend the works of the Anglo-Saxons and Chaucer or even the Great Bard, in the authentic tongue, but that doesn’t mean that they don’t enjoy listening to it, attuning their ear to the ancient voices of their ancestors. My own children are especially delighted when I venture off into Middle English, they listen all the more intently. So too, if I recite the Pater Noster in Anglo-Saxon or Old Norse. This means of course that I am given the impetus to learn and master these variations of my language.3 Despite certain advantages I gained through my education, I require practice, further knowledge, and I am almost starting from scratch with the more ancient forms of English. What a splendid thing it is for me. How wonderful to re-embrace this deep, folkish culture – to claim ownership of something. It is of far greater and more meaningful cultural significance than bellowing “oi,oi,oi”, with the national flag inauspiciously draped over my shoulders.

William Shakespeare 1564-1616. Chromolithography after Hombres y Mujeres celebres 1877, Barcelona Spain

It is saddening to see that most Australians of Anglo-Saxon heritage can’t recognise their roots prior to 1788, and that they are even hostile to the notion. How can you possibly know your place in time, space and history with a mindset like that? I can assure the reader that young Mohammed has no such attitude, nor does Kumaran or Yat-sen. They see their cultural roots as the base of an ancient and well grown tree, of which they are a shoot. A shoot that may shine in the Australian sun, but can feed itself from the well nourished Earth that it is grounded in – miles and millennia away. There is no reason why the Anglo-Saxon has to have his cultural instincts become as anaemic as he insists his complexion to be.

Such a simple thing as knowing the ‘canon’ of folkish literature that pertains to one’s heritage and then putting it into active family practice, is so vital yet so rarely executed. It is indeed the very first step in the reconquista of the culture wars. From this solid grounding, a deeper sense of true culture will grow – maybe one that inspires proper resistance to any attempt at eroding said culture.

When one imbibes deep folkish culture in this way, one is literally engaging in a conversation with one’s ancestors. The words and thoughts of one’s actual forebears are being transmitted and received. The value of such conversations has been recognised by sociologists:

Human beings need the help of their ancestors; they need the help which is provided by their own biological ancestors and they need the help of their ancestors of their communities and institutions, of the ancestors of their societies and their institutions… The loss of contact with the accomplishments of ancestors is injurious because it deprives subsequent generations of the guiding chart which all human beings, even geniuses and prophets need. They cannot create these for themselves in a stable and satisfying way.4

Along with a sense of growing cultural awareness are distinct benefits to the character of the individual. Most of these folk tales are designed to carry a moral message. For example, the fluid aristocracy that some would say is unique to Anglo-Saxons is expressed in the works of Chaucer:

Thus kan a squier doon a gentil dede

As wel as kan a knyght, withouten drede.5

In Beowulf, we find our protagonist stripping himself of his armour and weapons for his show down with the feared monster, Grendel:

I consider myself no poorer in strength

and battle deeds than Grendel does himself;

and so I will not kill him with a sword,

put and end to his life, though I easily might;

he knows no arts of war, no way to strike back,

hack at my shield-boss, though he be brave

in his wicked deeds; but tonight we two will

forego our swords, if he dare to seek out

a war without weapons – then let the wise Lord

grant the judgment of glory, the holy God,

to whichever hand seems proper to him.6

What better expression of ‘a fair go’ – so often trotted out as an ‘Aussie’ cultural value? Although the boasting of Beowulf comes back to haunt him, and the Lord is shown to be just indeed. Beowulf has a lot more philosophy and theology than offered here. What is described however – is easily comprehended by a six year old.

In the elegy, The Seafarer, one sees the humility that is conjoined to the sense of daring adventure, as the poet shows the precarious nature of life and how glory won is owed to the GOD above:

On Earth there is no man so self-assured,

so generous with his gifts or so bold in his youth,

so daring in his deeds or with such a gracious lord,

that he harbours no fears about his seafaring

as to what the Lord will ordain for him.7

Walter Geikie, A Grandchild Reading (1841)

These moral lessons become impregnated upon the psyche and closely associated with the culture and heritage. The exercise in continuing folk heritage becomes an exercise in the moral imagination. The telling of such tales in a family setting also prompts moral discussion and familial examples (not to mention a patent reminder to parents to set such examples themselves.

Of course there is one final facet of this traditional exercise that is truly grounded in the ‘permanent things’. That is, the books themselves. Often the old books, carefully preserved through affection for their contents, tell a story of their own. Recently I rescued, from an inner-city op-shop, a small work entitled Golden Words: A Book of Daily Readings for Boys and Girls, published just prior to the First World War. Inscribed inside the cover, in fountain pen ink, is a message from the giver of this book to its receiver that reads:

Like to the sunlight, gladdenning [sic], brightening all

Like to the dew which no man heareth fall

so let thy influence be

– 17/12/13

No doubt a message regarding faith, but what a different meaning such an inscription takes on for the new owner of this book a century later – where he seeks not just the Lord’s influence. Try getting such an unexpected treasure in an ‘ebook’! Let us be reminded then by the experience of others (and learn the humility to receive it):

There is a saying by William Butler Yeats that a man begins to understand the world by studying the cobwebs in his own corner. My experience has brought home to me the wisdom in this, and since the contemporary ideal seems to run the other way, confronting the youth first with the abstractions of universalism, collectivism and internationalism, I propose to say something on behalf of the historic and the concrete as elements of an education.8

If we are to preserve our cultural memory and have any sense of continuity between the generations, then we must take up cudgels and fight. The weapon of choice should first and foremost be, in the writer’s humble opinion, the maintenance of folk tradition in the hearth and home – from parent to child, from grandparent to grandchild. The effect of such will be lifelong, and more likely to insulate against the insidious forces of the modern world than any emergency measure implemented once the disease of post-modernism first starts to manifest its septic symptoms.

– Luke Torrisi

The author is a legal practitioner and the host of Carpe Diem, Sydney’s only explicitly Traditionalist and Paleoconservative radio programme broadcasting on 88.9FM, between 8:00 to 10:00pm, Mondays.

End notes

- Ezra Pound (William Cookson, ed.), Selected Prose 1909-1965 (Faber & Faber, London, 1973) p 131.

- For a full discussion of the importance of the moral compass to the Conservative disposition, please refer to the “Ten Principles of Conservatism” articulated by Russell Kirk. cf., R. Kirk, The Politics of Prudence (ISI Books, Wilmington Delaware, 1993) p 17 [SydneyTrads: an online extract is provided here]. In this work, Kirk stresses the notion of harmony as part of the enduring moral order. This emphasis is also acute in the school of Radical Traditionalism where notions of Cosmos over Chaos are said to be obtained by reattaching to the “radix” or “root” of genuine Tradition.

A superb exposition of this position is found in Julius Evola, Revolt Against the Modern World (Inner Traditions International, Rochester, Vermont, 1995) in particular see p xxxv: “Those who begin from a particular traditional civilisation are able to integrate it by freeing it from its historical and contingent aspects, and thus bring back the generative principles to the metaphysical plane where they exist in a pure state, so to speak – they cannot help but recognise these same principles behind the different expressions of other equally traditional civilisations. It is in this way that a sense of certainty and of transcendent and universal objectivity is innerly established, that nothing could ever destroy, and that could not be reached by any other means.” This approach would find greater sympathy with the actual recommendations of practice made here, the actual “living” of the tradition as opposed to the reverence of it.

A superb exposition of this position is found in Julius Evola, Revolt Against the Modern World (Inner Traditions International, Rochester, Vermont, 1995) in particular see p xxxv: “Those who begin from a particular traditional civilisation are able to integrate it by freeing it from its historical and contingent aspects, and thus bring back the generative principles to the metaphysical plane where they exist in a pure state, so to speak – they cannot help but recognise these same principles behind the different expressions of other equally traditional civilisations. It is in this way that a sense of certainty and of transcendent and universal objectivity is innerly established, that nothing could ever destroy, and that could not be reached by any other means.” This approach would find greater sympathy with the actual recommendations of practice made here, the actual “living” of the tradition as opposed to the reverence of it. - Of course the mainstay of the recommended exercise are simplified texts designed for children. These are becoming rarer to find, and in my personal experience, are the preserve of ‘rare’ or ‘antique’ bookshops. When there is no demand, then there is no supply. It would be good to see a renaissance of sorts, of Anglo-Saxon classic stories for children. Every so often one sees a glimmer of hope.

- Edward Shils, Tradition (Faber and Faber, London, 1981) p 326.

- Geoffrey Chaucer, “The Franklin’s Tale” in G. Chaucer (F. N. Robinson, ed.) The Canterbury Tales Vol II (The Folio Society, London, 1986) pp 373-374.

- R. M. Liuzza (trn.), Beowulf (Broadview, Toronto, 2000) pp 73-74.

- Kevin Crossley-Holland (trn.), From The Anglo-Saxon World: An Anthology (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1987) p 54.

- Richard M. Weaver, In Defense of Tradition (Liberty Fund, Indianapolis, 2000) p 33.

“It is saddening to see that most Australians of Anglo-Saxon heritage can’t recognise their roots prior to 1788, and that they are even hostile to the notion.”

According to Andrew Fraser, Anglos have lost their collective soul. In his book “The WASP Question,” he asserts that WASPs (White Anglo Saxon Protestants) accept prejudice against themselves and suffer from their own Anglophobia and ethnomasochism.

http://www.amazon.com/WASP-Question-Andrew-Fraser/dp/1907166297

Anglophobia is certainly prevalent in Australia, particularly among our “new class” elites. As Frank Salter writes:

“Anglo Australians are a subaltern ethnicity. They are second-class citizens, the only ethnic group subjected to gratuitous defamation and hostile interrogation in the quality media, academia and race-relations bureaucracy. The national question is obscured in political culture by fallout from a continuing culture war against the historical Australian nation. Many of the premises on which ethnic policy have been based since the 1970s are simply false, from the beneficence of diversity to the white monopoly of racism and the irrelevance of race. The elite media and strong elements of the professoriate assert that racial hatred in Australia is the product of Anglo-Celtic society. But in the same media and even in the Commission for Race Discrimination most ethnic disparagement is aimed at “homogenised white” people.”

http://207.57.117.110/magazine/issue/2012/11/the-war-against-human-nature-iii

http://www.quadrant.org.au/magazine/issue/2012/10/the-war-against-human-nature-iii-race-and-the-nation-in-the-media