At this year’s February Symposium, Mr. M. W. Davis issued a rousing call for Traditionalist men and women to return to traditional, national dress as an indispensable act of counterrevolution.1 I would not gainsay Mr. Davis — indeed, I have striven since then to follow his advice — and yet, as the fateful fourteenth of July approaches, I find myself preparing to don a garment which has become traditional for me, but not yet for anyone else.

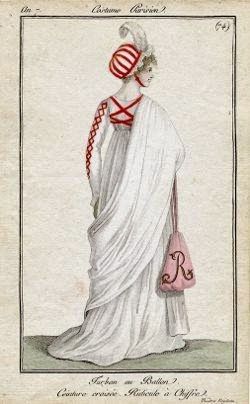

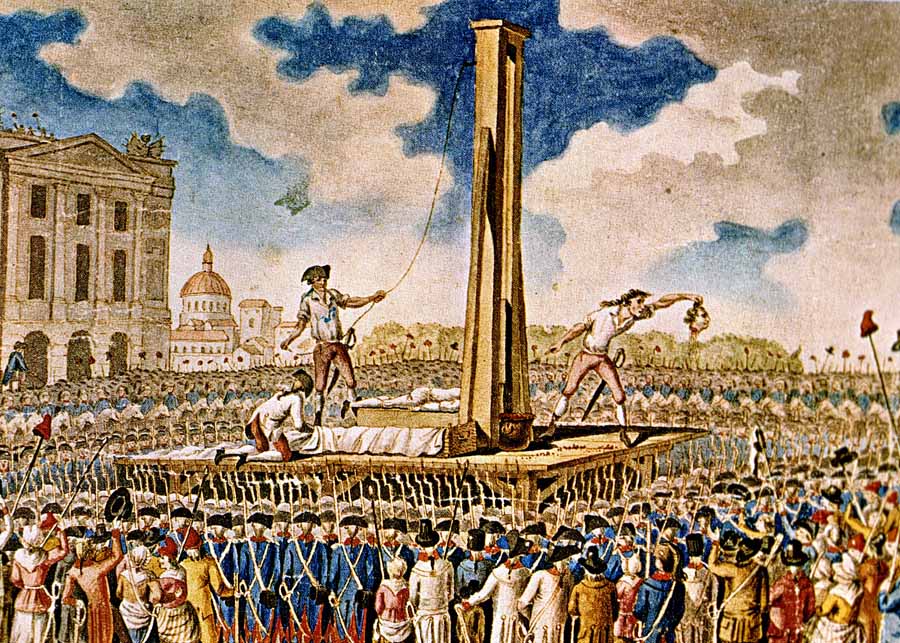

Historians debate whether they are historical fact or urban legend but, in either case, the Parisian bals des victimes2 are, to my mind, a myth for our times. The story goes that, in the wake of the French Revolutionary Terror, the bereaved relatives of those who had kissed the guillotine eschewed customary rites of mourning to hold lavish balls which only those who had so lost a relative were eligible to attend. There, dances commenced not with the usual gentle nod, but with a sharp, downward jerk of the head that imitated decapitation, while both men and women coiffured themselves à la victime — with hair longer and often curled in front, but shorn off in the back at the neckline, just as the executioners had done in order to clear the path of the blades. A variety of fanciful ensembles, often based on or incorporating mourning clothes, graced these events, but one key accessory appears time and again—a red ribbon tied around the neck at the point where a guillotine blade would fall.

The bals, it is sometimes suggested, were an invention of the royalists’ Jacobin enemies, intended to discredit them through a shocking description of hedonistic irreverence. If so, the effort was largely successful. Republican writers found in them a seemingly perfect encapsulation of aristocratic decadence, while royalists excoriated the idea of such a flagrant transgression of the old usages of mourning. Interestingly, both lines of attack have contemporary echoes in debates over the practice, which some young Israelis have embraced in transgression of Leviticus 19:28, of having the numbers of relatives who endured the concentration camps tattooed on their own arms3 — to some, a powerful tribute, to others, a macabre mockery.

The bals, it is sometimes suggested, were an invention of the royalists’ Jacobin enemies, intended to discredit them through a shocking description of hedonistic irreverence. If so, the effort was largely successful. Republican writers found in them a seemingly perfect encapsulation of aristocratic decadence, while royalists excoriated the idea of such a flagrant transgression of the old usages of mourning. Interestingly, both lines of attack have contemporary echoes in debates over the practice, which some young Israelis have embraced in transgression of Leviticus 19:28, of having the numbers of relatives who endured the concentration camps tattooed on their own arms3 — to some, a powerful tribute, to others, a macabre mockery.

Mockery, however, is a more serious thing than it is often taken to be. Every traditional society has made a space for it in some kind of Saturnalia — crowning a prince des sots to invert the natural order for a day and to whisper in the ears of the tribunes that all worldly glory is fleeting. The survivors of the Terror, however, found that the world had been turned upside down not for a day, but for what is now over two centuries. In response, they set up a prince des sots who was, at least metaphorically, a real prince, to sing through the ballrooms of Paris that the glory of one who has changed a corruptible crown for an incorruptible is deathless.4

For three hundred sixty-four days of the year, it is true what Mr. Davis says, that “We have to live as though society is correctly ordered and encourage others to follow our example.” Yet we, like Caesar in his chariot, must be careful not to deceive ourselves. This society is not correctly ordered, and lest we allow the memory of better times to tarnish, and lose the impetus behind our grand example through the remainder of the year, it behooves us to make a ritual reënactment that partakes a little of the absurdity of sotie, that we may be reminded that, just as the wisdom of the world has been made foolish, the wisdom of the ages has been made to appear so.

I trust, then, that Mr. Davis will not begrudge me the departure from tradition, and even more so from Anglo-Saxon costume, represented by one day’s donning of a crimson ribbon worn about the neck, in memory of all those martyrs whom the Orthodox Church, in its recent enthusiasm for the monarchical principle, has not yet seen fit to commemorate more fully. Perhaps, in a spirit of (if I may be pardoned the expression) fraternité, you will don one with me.

– Race MoChridhe is an academic researcher in the fields of religious and women’s studies. His writing outside academia, consisting primarily of essays and poetry in multiple languages, has been featured in The Montreal Review, the Asahi Shimbun, Feminism & Religion, and Good Words for the Young: A Children’s Devotional, among other publications. He blogs at <www.racemochridhe.com>

Endnotes:

- Michael W. Davis, “Fogeyism: in Theory and Practice” SydneyTrads (11 February 2017) <sydneytrads.com> (accessed 9 July 2017).

- Ronald Schechter, “Gothic Thermidor: The Bals de victims, the Fantastic, and the Production of Historical Knowledge in Post-Terror France” Representations No. 61 (Winter, 1998).

- Jodi Rudoren, “Proudly Bearing Elder’s Scars, Their Skins Says ‘Never Forget’” The New York Times (30 September 2012) <nytimes.com> (accessed 9 July 2017).

- King Charles, his Speech, Made upon the Scaffold at Whitehall Gate, Immediately before his Execution, on Tuesday 30 January 1648, With a relation of the manner of his going to Execution – Published by Special Authority – 1649. [Care of Project Canterbury (undated upload) <anglicanhistory.org> (accessed 9 July 2017)].

Leave a comment