“Thus democracy appeared to have the self-evidence of an irresistible advancing and expanding force. So long as it was essentially a polemical concept (that is, the negation of established monarchy), democratic convictions could be joined to and reconciled with various other political aspirations. But to the extent that it was realized, democracy was seen to serve many masters and not in any way to have a substantial, clear goal. As its most important opponent, the monarchical principal, disappeared, democracy itself lost its substantive precision and shared the fate of every polemical concept. At first, democracy appeared in an entirely obvious alliance, even identity, with liberalism and freedom. In social democracy it joined with socialism. The success of Napoleon III and the result of Swiss referrenda demonstrate that it could be conservative and reactionary, just as Proudhon prophesied. If all political tendencies could make use of democracy, then this proved that it had no political content and was only an organizational form; and if one regarded it from the perspective of some political program that one hoped to achieve with the help of democracy, then one had to ask oneself what value democracy itself had merely as a form. The attempt to give democracy a content by transferring it from the political to the economic sphere did not answer the question.”

“Thus democracy appeared to have the self-evidence of an irresistible advancing and expanding force. So long as it was essentially a polemical concept (that is, the negation of established monarchy), democratic convictions could be joined to and reconciled with various other political aspirations. But to the extent that it was realized, democracy was seen to serve many masters and not in any way to have a substantial, clear goal. As its most important opponent, the monarchical principal, disappeared, democracy itself lost its substantive precision and shared the fate of every polemical concept. At first, democracy appeared in an entirely obvious alliance, even identity, with liberalism and freedom. In social democracy it joined with socialism. The success of Napoleon III and the result of Swiss referrenda demonstrate that it could be conservative and reactionary, just as Proudhon prophesied. If all political tendencies could make use of democracy, then this proved that it had no political content and was only an organizational form; and if one regarded it from the perspective of some political program that one hoped to achieve with the help of democracy, then one had to ask oneself what value democracy itself had merely as a form. The attempt to give democracy a content by transferring it from the political to the economic sphere did not answer the question.”

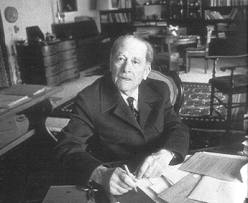

▪ Carl Schmitt, The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy (Duncker & Humbolt, 1923; MIT Press, trn. Ellen Kennedy, 1985) extract from page 24.

Be the first to comment on "Quote of the Week: Carl Schmitt, “The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy”"