I

Introduction

Jürgen Moltmann

Biblical interpretation is, if not the only, certainly the core task of theological hermeneutics. Unfortunately, religious conflict and biblical interpretation have always been joined at the hip. Is it therefore the case that theologians engage in “politics” when they offer authoritative interpretations? Is it too much of a stretch to characterize biblical hermeneutics as a branch of political theology? It does seem that biblical interpretation fits comfortably within almost any definition of the “political”. Politics is commonly associated with power. And he who controls the interpretation of the Word of God sets boundaries between Christian orthodoxy and heresy; he also shapes and sanctifies the ecclesiastical role in relationships between faithful Christians and their triune God. Indeed, the “political” nature of theological hermeneutics becomes self-evident the moment priests, pastors, and professors try to define what they mean by “politics”.

When Christian thinkers in the modern West turn their minds to politics, they generally fall somewhere along a spectrum stretching from those most attracted to cosmopolitan humanism to those characterized by a more parochial or patriotic political realism. The humanists, perhaps typified by the German Reformed theologian Jürgen Moltmann, espouse a future-oriented, eschatological vision of politics. Moltmann portrays politics as “the search for forms of human association and for uses of the powers of nature which foster the realization of full human life”.1 This global vision of Christian politics stands in stark contrast to the more national focus of another famous German political theologian, the Catholic jurist Carl Schmitt. Highly sceptical of liberal humanism, Schmitt believed that the political has to do with the existential conflict between friend and enemy.2

II

The Resurrection as a Problem in Political Hermeneutics

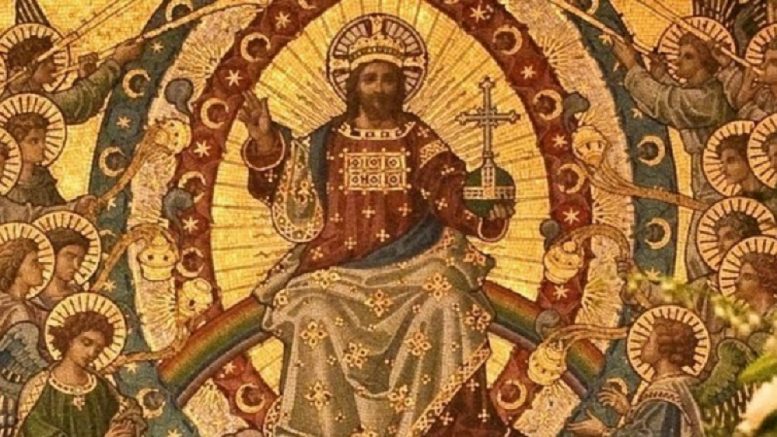

In effect, Moltmann’s political “theology of hope” grounds Christian faith in an ontology of peace set in opposition to the ontology of violence he saw in Schmitt’s hard-nosed historical realism.3 Whether such differences over the definition of the political are ontological or merely historical, the tension between cosmopolitan and parochial perspectives is baked into the cake of biblical hermeneutics. Even scholarly disputations over the resurrection of Jesus Christ are filtered through explicitly political interpretations of biblical texts. Political theology cannot be swept under the rug. The stakes are too high. The survival of Christianity as we know it depends upon its capacity to maintain the faith in the risen Christ set out, inter alia, in the Nicene Creed:

For our sake [Jesus Christ] was crucified under Pontius Pilate; he suffered death and was buried. On the third day he rose again in accordance with the Scriptures; he ascended into heaven and is seated at the right hand of the Father. He will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead, and his kingdom will have no end.

Individual believers, no less than various branches of the church universal, have vital interests, spiritual and material, in the perceived truth and/or utility of their version of the resurrection story. Theological hermeneutics is, has been, and forever will be in search of the “proper” interpretation of the “paschal mystery” at the heart of the Easter story.

Carl Schmitt

Certainly, it is becoming painfully obvious that the ongoing quest for the “true” meaning of Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection cannot be separated from the central political conflict of our time: globalism versus nationalism. Can it be mere coincidence that interpretations of the Easter story portraying the crucified-and-resurrected Messiah as a “global Jesus” are a staple of mainline Protestant preaching? “Global” Christianity teaches that the bodily resurrection of Jesus Christ represents the hope of a still-future resurrection of the dead for the whole of “humanity”. Accordingly, most professing Christians would greet the very idea of a “national Jesus” as an oxymoron at best and a heresy at worst. But just as secular nationalism has arisen in opposition to the process of globalization in the temporal realm of politics, a growing number of Christian scholars, across a range of disciplines, now offer a “national Jesus” as a compelling alternative to the globalized interpretation of the resurrection story.

In the emerging story of “national Jesus,” neither the historical Jesus nor his apostle Paul offer a vision of the future extending beyond the then-imminent, spiritual restoration of national Israel. Among historians it is not at all controversial to observe that “Jesus’ God was the national God of Israel, not some abstract universal deity”.4 Moreover, Jesus made it clear that his impending death “concerned Israel as a nation”. He did not want to create a “new religion. He wanted to consummate God’s promises to Israel, and he saw this taking place in the land of Israel”.5

Outside the historical profession, a dissident band of biblical exegetes reject the traditional church doctrine that the crucifixion-and-resurrection represent the fulfillment of Israel’s covenantal history.6 These “preterist” (from the Latin, præter, meaning “past”) scholars locate both the Easter story and the subsequent parousia (a.k.a. the Second Coming) of Jesus Christ in the first century AD. The story of Jesus, they say, is an epic narrative inextricably bound up with the historical destiny of national Israel. If they are right, the covenantal eschatology inscribed in the biblical metanarrative tells us nothing about the future of “humanity”.

Brian Robinette

The resurrection of Jesus Christ was, as the creeds affirm, a shadow or a type of a second, general resurrection. But, preterists contend, the resurrection of the dead of which the apostle Paul spoke was a spiritual process occurring there and then in the first century; he was not expecting the physical bodies of dead people to climb out of the grave. Jesus did not appear in bodily form to Saul or his companions on the road to Damascus (Acts 9:3-8). His spiritual presence represented “the firstfruits of them that slept” (1 Cor 15:20); namely, the Old Testament saints together with those in Paul’s generation who had “fallen asleep” in Christ. The resurrection body of Christ was transfigured into the fulfilled telos of national Israel according to the flesh. On this biblical hermeneutic, the vindication of the martyrs, the spiritual restoration of Israel, was consummated with judgement at the Day of the Lord marking the end of the Mosaic Age. In short, the apocalyptic destruction of the temple in Jerusalem in A.D. 70 inaugurated the new heaven and a new earth.7

Anyone who reads the Easter story faces a hermeneutic choice: global Jesus or national Jesus. Whether or not we recognize the fact, the hermeneutic judgement we render on that issue has political significance. Historical criticism and covenantal eschatology, separately and together, provide growing support for a hermeneutic of resurrection centred on a national Jesus. Thus far, however, those who challenge the hermeneutical hegemony of “global Jesus” have been, for the most part, blind to the implications that a national Jesus carries into the realm of contemporary political theology. On the other hand, the progressive champions of global Jesus have been much less reticent. Indeed, like Moltmann, the “postmodern critical Augustinians” who now carry the torch for the political theology of hope wear their politics proudly on their sleeves.8

III

Global Jesus as Universal Victim

For Brian Robinette, “the language of resurrection is cosmic in scope,” extending in time and space far beyond the Sitz im Leben of biblical Israel. He upholds the traditional view that the crucifixion-and-resurrection of Jesus was “the precondition for Israel becoming the ‘light unto the nations’”. In the course of his ministry, Jesus had demanded righteousness and obedience from his followers. He insisted that Israel’s hope for restoration was crucially dependent upon repentance and forgiveness of sin. Flying in the face of such warnings, “Jesus’ crucifixion stands as the ultimate expression of human sin and guilt”. God’s response is utterly astonishing: by raising Jesus from the dead, God extends an “offer of forgiveness to Israel”. God made Israel a light unto the nations, first, by raising Jesus from the dead, thereby serving “eschatological justice to an innocent victim whilst unmasking the guilt of his accusers and murderers”. At the same time, by resurrecting Jesus from the dead, God acquits “those responsible for this death, using their own ignorance and sin as the very means to save them from self-condemnation” by welcoming the return of the risen victim.9

Robinette maintains that this acquittal applies to every human person. All of us who have denied hospitality to the Other now have the opportunity “to participate in a new community, the ecclesia, founded upon the welcome of the victim”. Within the redemptive logic of Israel’s own story, therefore, God’s offer of forgiveness is “universal in its breadth”.10 The death of the “risen victim […] manifests the sin of the world in which all are implicated”.11 The Easter story is not just about an historical event long ago and far away for which we carry no responsibility. Both justice and mercy are extended to all human persons when God vindicates “an innocent victim from the dead”.12 The human spirit bears collective guilt for an historical crime even though we were not physically present where and when it was committed. The sin, guilt, and forgiveness of which Robinette writes are ontological, not historical, in nature.

Saint Augustine (354-430 AD)

In effect, like Augustine of Hippo long before him, Robinette rewrites the metanarrative of biblical Israel as the as-yet-unfinished story of humanity-at-large. He presents the crucifixion-and-resurrection story as an ahistorical, onto-theological drama. It was not just the disciples who were passively complicit in “Jesus’ lynching”. All of us “are entrenched in the dynamics that led to Jesus’ death—including you, dear reader”. We may not be “literally contemporaneous with the events that led to Jesus’ crucifixion in first-century Jerusalem” but “we are contemporaneous insofar as the dynamics involved in his crucifixion are operative in our own lives. Had we been there, the text is urging, we would have done the same thing”.13 We, too, would have violently expelled Jesus from Israel’s midst. Sharing in the ontological guilt of the historic perpetrators of deicide, we, too, must pray for forgiveness.

For Robinette, the bodily resurrection of Jesus was both a demonstration of God’s power and a “universal offer of forgiveness to humanity”. By raising Jesus from the dead, God “overcomes death itself. It transforms death’s absolute non-presence into God’s self-presence to us in the crucified-and-risen One”. God triumphs “over those structural powers, including death itself, that led to the brutal death of God’s eschatological prophet; thus, the message of Easter draws our attention to God’s solidarity with the victims in our history”. Two thousand years after the empty tomb was discovered, Robinette believes, the “eschatological counter-gaze of the forgiving victim” still invites us to perceive just how deeply engrained are the processes by which we obtain our “identity, whether individually or in groups, through the expulsion of the Other”. Christian reflection on the resurrection “unseals the collective amnesia that has allowed us to suppress the injustice of our violent exclusions, showing once and for all that the effort to build our identities through the denial of hospitality to the human Other—is in fact a rejection of the divine Other”.14

Whenever and wherever Christians welcome “the Gift of the risen victim,” the heavenly ontology of peace finds its earthly abode. Historically speaking, the ontology of violence gave way incrementally to an ecclesiastical realm of peace on earth. Robinette holds that the second, general resurrection is a real historical process which began in the first century church and continues today. The already-but-not-yet resurrection of the dead has guided us “into a new story whose truth can set us free for full human flourishing”.15

IV

Global Jesus and the Christian Hermeneutics of Mission

Robinette is convinced that the “human person” becomes a “catholic personality” by allowing “the Spirit of the risen Christ to graciously penetrate our self-enclosed patterns of perception and behaviour, and to disarm those many defences that prevent us from allowing the Other to be welcomed as co-constitutive”. Openness to the Other promises an “enrichment of the self” as we become “a personal microcosm of the eschatological new creation”. In that way, “we anticipate (or ‘analogize’) the general resurrection of the dead in which God will be all in all”. Human personhood is sanctified through a transition from a life “dominated by sinful existence to genuine freedom,” a transition which “comes only by welcoming an Other whose alterity is not an obstacle to human flourishing but the condition of possibility for it”.16

Alasdair John Milbank

On this interpretation, the cross and resurrection are not mere signs of forgiveness. Like Robinette, John Milbank believes that “Jesus’ death is efficacious […] also as a material reality”. This is “because it is the inauguration of the ‘political’ practice of forgiveness; forgiveness as a mode of ‘government’ and social being”. Milbank describes this practice as “itself ongoing atonement”. In other words, if atonement is “to be materially efficacious it cannot be ‘once —and for all’, like the sign or metaphor of atonement,” it “must be continuously renewed”.17

Both Milbank and Robinette turn to political thought and action as a means of making atonement effective in the real world. Robinette suggests that because “sin replicates itself through interpersonal, social, and cultural relations,” the central theme of atonement is the idea of a divine victory over the evil powers of the world. He warns us never to “lose sight of the fact that Jesus was crucified by a political power”. Of course, Jesus himself had no interest in obtaining political power but “his ministry was profoundly political insofar as it sought to reorient our social construction of reality”. Indeed, Jesus was put to death “as a political criminal because he represented a thoroughgoing challenge to the way we order interpersonal and social relationships, above all the way we order our world through the production of victims”. By participating in God’s “alternative Kingdom” we aim to embody the risen victim by means of solidarity “with the victims of our world”. It means associating “with those who are deemed the outsiders, the contaminants, the monsters, the prisoners, the dispensable, and the unclean according to the dominant purity maps in any given social-cultural setting”.18

In today’s political climate, Robinette’s vision of Christian political practice seems indistinguishable from fashionably progressive purity spirals. He is unlikely to face ostracism from academic colleague when he declares that the “ministry of reconciliation is one that puts the Christian in a mode of service to the Other”. All right-thinking people — especially people of European heritage or descent — are under constant pressure “to become highly sensitized and responsive to those social mechanism that produce victims”. Not even the most enthusiastic globalist or leftist proponent of mass Third World immigration would object to Robinette’s claim that “[b]y offering hospitality to those who suffer expulsion or want, we offer hospitality to Christ himself (Matt. 25:34-46)”.19 Indeed, Robinette simply follows in the footsteps of Jürgen Moltmann’s footsteps when he offers a “political interpretation of biblical eschatology […] indebted to the philosophy of revolution of Hegel, Marx, and Ernst Bloch”.20

Karl Marx (b. 1818 d. 1883)

Contrary to popular misconceptions, Marx’s attitude towards Christianity was not exhausted by his famous dictum that “religion is the opium of the people”. Far from being opposed to religion per se, Marx sought to make “the living protest garbed in religious myth practically effective”. Recognizing the power latent in religious mythology and ritual, Marx aimed to bring about “an historical realization of religion …] by translating myth into action”.21 The political hermeneutic utilized by both Moltmann and Robinette parallels radical Marxist protests against oppression. Both proclaim “the liberation of the suffering creation out of real affliction”.22 Both believe that the “proper interpretation of the gospel is its historical realization”. Robinette shares Moltmann’s conviction that Christian hermeneutics is an inescapably political “hermeneutics of mission”.23

Biblical interpretation thus becomes a way of promoting revolutionary change in historical time in the name of the risen victim. Moltmann, like Robinette, uses the biblical images of the “needy and the outcast, and foremost of the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus as clues to the purpose and goal of God’s activity and his summons to man”. The image of global Jesus as universal victim transforms the gospel into “a power which intensifies and universalizes the quest of man for an all-embracing community of justice and freedom”. By arousing the hope of “God’s coming universal reign,” the gospel of the risen victim “provokes men to resist the institutional stabilization of present conditions”.24

But it is not just institutional life that will be destabilized by this Christian humanist dialectic of atonement. Human beings no longer “have to try to cling to their identity through constant unity with themselves, but will empty themselves into non-identity […] into what is other and alien”.25 Robinette insists that Christians must set out to undermine “every tendency to build our identities according to ‘us’ and them’”. Atonement requires “a ‘catholic’ identity that welcomes the Other in hospitality”.

Robinette acknowledges that such a political hermeneutic flatly denies the existential distinction between “friend” and “enemy”. In fact, the truly radical character of Christian hospitality toward the Other only “comes into focus when we consider that this Other may be our ‘enemy’”. We imitate global Jesus most faithfully “when we engage with love those who persecute us”.26

Here, however, we should be aware that, as a matter of fact, Jesus did not ask his listeners to “love” their persecutors in the Sermon on the Mount; rather, he urged prayers on their behalf. It is even more important to realize what Jesus meant when asked the audience to love their enemies. In the Greek, he refers specifically and only to “private” enemies (echthros) not to “public” or “alien” enemies (polemoi).27 Unless one keeps such distinctions in mind, a Christian hermeneutics of mission can easily degenerate into pathological altruism.28 The existential distinction between friend and enemy cannot be dissolved by transforming Christianity into a deracinated, cosmopolitan cult of the Other. National Jesus knew better than to mistake historical choice for ontological essence.

[Part II will be published this coming Friday]

Andrew Fraser was born, raised, and educated in Canada and the United States of America. He taught constitutional law and legal history for many years at Macquarie University, Sydney Australia and is the author of The WASP Question, an inquiry into Anglo-Saxon identity in the context of the modern, globalising world. His Dissident Dispatches is based on his recent experience earning a Bachelor of Theology degree from Charles Sturt University.

Andrew Fraser was born, raised, and educated in Canada and the United States of America. He taught constitutional law and legal history for many years at Macquarie University, Sydney Australia and is the author of The WASP Question, an inquiry into Anglo-Saxon identity in the context of the modern, globalising world. His Dissident Dispatches is based on his recent experience earning a Bachelor of Theology degree from Charles Sturt University.

Endnotes:

- Daniel L. Migliore, “Biblical Eschatology and Political Hermeneutics” Vol 26 No. 2 Theology Today (1969) p. 116, at p. 118.

- Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political George Schwab (trans.) (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1976) p. 26.

- Jürgen Moltmann, Theology of Hope (New York: Harper & Row, 1967); Carl Schmitt, Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty George Schwab (trans.) (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1988).

- Scot McKnight, A New Vision for Israel: The Teachings of Jesus in National Context (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1999) p. 69

- Ibid., p. 6

- Cf. Brian D. Robinette, Grammars of Resurrection: A Christian Theology of Presence and Absence (New York: Crossroad Publishing, 2009) p. 294.

- One of the most prolific preterist scholars is Don K. Preston who has published too many books to list here. One useful introduction to his work is: Don K. Preston, We Shall Meet Him in the Air: The Wedding of the King of Kings! (Ardmore, OK: JaDon Management, 2009).

- Cf. John Milbank, “‘Postmodern Critical Augustinianism’: A Short Summa in Forty Two Responses to Unasked Questions” Vol. 7 No. 3 Modern Theology (1991) p. 225.

- Robinette, op. cit., pp. 309, 294-295.

- Ibid., pp. 293-294.

- Ibid., pp. 309-310 emphasis in original.

- Ibid., p. 309.

- Ibid., pp. 293-294.

- Ibid., pp. 296, 309-310, 301.

- Ibid., p. 293.

- Ibid., pp. 309, 305.

- John Milbank, “The Name of Jesus: Incarnation, Atonement, Ecclesiology” Vol. 7 No. 4 Modern Theology (1991) p. 311, at p. 327.

- Robinette, op. cit., pp. 304, 312-313.

- Ibid., p. 307.

- Migliore, op. cit., p. 122.

- Ibid., p. 122.

- Moltmann, quoted in ibid., p. 123.

- Ibid., p. 123.

- Ibid., p. 128-129.

- Moltmann, quoted in Robinette, op. cit., p. 309.

- Ibid., p. 311.

- Cf. Schmitt, Concept of the Political, p. 28-29.

- Cf. Barbara Oakley, et. al., Pathological Altruism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).

Leave a comment