I

Introduction

From its beginnings in the first century A.D. Christianity anchored its cosmology in the Bible. But what is the Bible? As a book in hand, of course, it is a collection of ancient texts, the product of the religious history of a remarkably durable and professedly holy ethno-nation in the ancient Near East. One might well ask, therefore, just what spiritual truths or religious guidance could, or should such a book convey to people like me, specifically, Anglo-Saxon Protestants living in the twenty-first century? Is the Holy Bible just another “social construct,” a mere cultural artifact, or is it instead the literal Word of God?

Karl Barth (1886-1968)

Intellectual heavyweights among mainline Anglo-European Protestants such as Karl Barth concede that the Bible is indeed a “humanly composed and selected” collection of “human words” while professing a neo-orthodox faith that scripture remains “the witness of divine revelation”.1 But how should faithful Christians interpret the testimony of that witness? Or, should we say “witnesses”? After all, Protestants differ with Catholics as to whether this or that ancient Hebrew or Jewish text should be included in the biblical canon. At the end of the day, however, even if all churches somehow settle upon on a single, canonical corpus of antique texts, the theological significance of the biblical metanarrative, from Genesis to Revelation, will remain open to competing interpretations—as it always has been.

The difficulty of distinguishing heresy from orthodoxy forced the early church to master the art of theological hermeneutics. The church fathers expounded the Word of God using a bewildering variety of literal, allegorical, moral, and anagogical (mystical) methods of biblical interpretation. In quick succession, rival camps staked out their respective claims to the true or most useful understanding of the Bible story. First in best dressed were the mostly Hebrew and Jewish authors and participant observers responsible for the original texts of both the Old and New Testaments. Marinated in Scripture, the Mosaic law, and the prophetic tradition, they read and told their stories of the creation, fall, and redemption of Old Covenant Israel through an ethnocentrically thickened, Hebraic hermeneutic lens. Their insider’s view of the Hebrew religious culture revolving around the Jerusalem Temple was far removed from the cosmopolitan, Hellenic, or Greco-Roman presuppositions underlying the Christian tale of two cities told several centuries later by Augustine (354-430 AD) the bishop of Hippo in North Africa.

II

Augustine Rewrites the Bible Story

In effect, Augustine had to re-invent the Bible story. According to a Hebraic hermeneutic grounded in the salvation history of Old Covenant Israel, the narrative ends sometime in the first century AD, just before the destruction of “the great city…where also our Lord was crucified” (Rev. 11:8). Augustine rewrites the end of the Bible story by projecting the end times into the future of his own Christian age. He reads Revelation as a prophecy of the apocalyptic Day of Judgement still in store for the earthly City of Man. He also put his own dramatic spin on the creation stories in Genesis 1-3.

Saint Augustine (354-430 AD)

By both precept and example Augustine prescribed authoritative hermeneutic rules and techniques designed to accomplish the twin tasks of understanding the Bible oneself and then teaching others orthodox Christian doctrine.2 Augustine not only provided a compelling doctrinal foundation for the formal Creeds of the church; he also helped to secure the actual historical triumph of the church. He held out the hope that a novel Christian cosmopolis could bring peace, order, and good government to a chaotic, multicultural mélange of peoples during the dying days of the Roman Empire in the West. Augustine’s interpretation of the bible story brought the heavenly City of God down to earth as the mythomoteur or constitutive myth for a new race of Christians.3 He provided his fellow Christians with a coherent sense of who they were as a people, where they came from, and where they were going. Augustine’s Hellenistic hermeneutic was an earthly success; it inspired a reverence for ecclesiastical Tradition which still guides Christian interpretations of Sacred Scripture along approved paths.

One example of the importance of Tradition in contemporary theological hermeneutics is the scholarly movement known as Radical Orthodoxy (hereafter, RO). This group of mainly academic writers and thinkers represent an Anglo-Catholic style of “postmodern critical Augustinianism”.4 Like Augustine, writers such as John Milbank and Catherine Pickstock seek to demonstrate their orthodoxy by promoting theology as the restored queen of the sciences to whom philosophy must pay obeisance.5 Unlike Augustine, however, they are philosophical radicals with scant interest in Biblical exegesis. RO much prefers to engage in theological entryism, courting the post-modern heirs of Augustine’s Hellenic neo-Platonism. An outspoken Remainer and cosmopolitan xenophile, Milbank is on a mission to wean continental intellectual leftists away from an increasingly satanic secularism. In place of the hegemonic “globohomo” liberalism of the transnational corporate welfare state, Milbank promotes a neo-Augustinian politics of virtue which aims to “immanentize the eschaton” by bringing the heavenly City of God back down to earth.6

Alasdair John Milbank

Not surprisingly, such theological dalliances with the spiritual heirs of Marx and Freud deepens the widespread suspicion among the many neo-pagan thinkers of the ideological right that “Christianity was essentially an alien, even subversive, Jewish ideological influence on European civilisation, and one which has been, at least in some ways, incompatible with the culture of Europeans”.7 According to Alain de Benoist’s dismissive reading of the Bible, for example, “Judeo-Christian monotheism” posits “universal peace” as “an ideal at the end of history”.8 As we will see, this simplistic interpretation of the bible story owes more to St. Augustine of Hippo than to the Hebraic hermeneutic through which Jewish Christians viewed the origins, history, and destiny of Old Covenant Israel.

The Apostles Peter, Paul, and John, for example, clearly looked forward eagerly to the imminent end—in their own generation—of the Mosaic Age. They expected the story of Old Covenant Israel to reach its apocalyptic conclusion in the first century AD, not at the end of human history. Peter and Paul were Jews, that is true. But they did not invent the millenarian Christian eschatology sanctified by ecclesiastical Tradition. That futurist Biblical hermeneutic was pioneered by Augustine of Hippo, himself the product of a Greco-Roman rather than the Hebraic hermeneutical tradition. Richard Storey is one of many scholars who concludes, therefore, that “Christianity is Hellenistic, a rightful successor of the natural law tradition” and “that it lies at the heart of Western civilisation”.9 Such a judgement, of course, begs the question of whether either the Hebraic or the Hellenistic hermeneutic offers a true or useful understanding of Sacred Scripture. To answer such a question, we must first compare the two.

III

Hebraic Hermeneutics

Ancient Hebrew culture presupposed a cosmology alien to the modern mind. Strange though it seems to us, on a Hebraic reading, the story of creation in Genesis One has nothing to do with the origins of matter. Rather, like other ancient Near Eastern peoples, Israelites “believed that something existed not by virtue of its material properties, but by virtue of its having a function in an ordered system”.10 In other words, “what was most crucial and significant” to the biblical “understanding of existence was the way that the parts of the cosmos functioned, not their material status”.11

Richard Storey

As John Walton observes, Genesis One therefore offers an account “of functional origins rather than…of material origins. Consequently, to create something (cause it to exist) in the ancient world means to give it a function, not material properties”. On this view, the cosmos presupposed by the creation account begins “with no functions rather than no material”. The “function of any given thing within the entire cosmos conceived as a divine temple has to do its purpose rather than its material properties”. For ancient Hebrews, a temple was a symbol of the cosmos. “This interrelationship makes it possible for the temple to be the center from which order in the cosmos is maintained”. Genesis One describes the creation of the cosmic temple with all of its functions and with God dwelling in its midst”.12

Preoccupied with the function of things rather than their origins, “[b]iblical texts nowhere state or argue for creatio ex nihilo”. Creation was conceived, instead, as an organizational process intended to bring order out of chaos. James Hubler notes that these “texts are strangely quiet about the material for the cosmos”. Down to the first century AD, even Hellenised Jews simply presupposed creatio ex materia. To propose creation ex nihilo “would have been a unique position and could never have been justified without considerable explanation or argumentation”. 13

For ancient Hebrews and first century Jews alike, a materialist account of creation would have been pointless. They were committed to the function of the temple as the focal point of cosmic order, not just in the here and now but also in the Messianic Kingdom to come. It went without saying that not all cosmic temples in the Near East were created equal. Only the temple of the Hebrews in Jerusalem mattered to them. Hebraic hermeneutics presupposed a self-conscious and explicit ethno-theology. The highly particularistic ethno-religion of Old Covenant Israel remained resistant to the cosmopolitan and universalistic spirit of Greco-Roman culture at the advent of Jesus Christ. Indeed, the previously unknown concept of Judaism was invented only in the second century BC, around the time of the Maccabean revolts, in order to encourage Judean resistance to the culturally subversive influence of Hellenism.14

John Walton

Contemporary WASP theological hermeneutics is far removed from such an unabashedly ethnocentric mindset. Even someone as steeped in ancient Near Eastern cultures as John Walton more or less automatically reads the second creation story in Genesis 2-3 as an account of human, as distinct from Israelite, origins.15 It has long been “standard doctrine” among Christians “that every member of the human race is descended from the biblical Adam”. How interesting, therefore, that it was a seventeenth century “Calvinist of Portuguese Jewish origin from Bordeaux” who challenged Christian orthodoxy with the “beguilingly simple” claim “that human beings existed before the biblical Adam”.16

Isaac La Peyrère (1596-1676), who was most likely a Marrano Jew, resurrected ancient Hebraic hermeneutics by tracing “ceremonial Judaism…back beyond Moses to the Garden of Eden and thus to Adam himself”.17 In support of this novel Biblical interpretation, La Peyrère offered “a fresh if rather naïve” exegesis of Romans 5:12-14. He aimed to show that sin, and hence other human beings, had been in the world before Adam. “By this neat piece of exegetical reshuffling” La Peyrère effectively conjured “a range of irritating inconsistencies in the Genesis record…out of existence” with “a ready-made explanation for Cain’s fear, after his banishment from the Garden of Eden, that he would encounter hostile individuals seeking to kill him; it delivered a population to inhabit the city he built; it provided a possible answer to the question about where his wife came from”.18

La Peyrère’s impact on theological hermeneutics is such that many contemporary Christian scholars now accept that, according to Hebraic hermeneutics, Adam need not be, and probably was not conceived as the first human being. Rather, the Biblical Adam is best understood as proto-Israel. Adam’s story “is not about universal human origins but Israel’s origins”.19 Thus, the story of Adam

“mirror’s Israel’s story from exodus to exile. God creates a special person, Adam; places him in a special land, the garden; and gives him law as a stipulation of special communion with God (not to eat of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil). Adam and Eve disobey the command and … their punishment is death and exile from paradise.”20

Similarly, “Israel was ‘created’ at the exodus … and brought to the good and spacious land of Canaan”. Israel was also bound by a law which it continually disobeys with the result that Israelites are exiled from the holy land which God gave them. In this way “Israel’s drama—its struggles over the land and failure to follow God’s law—is placed into primordial time”.21

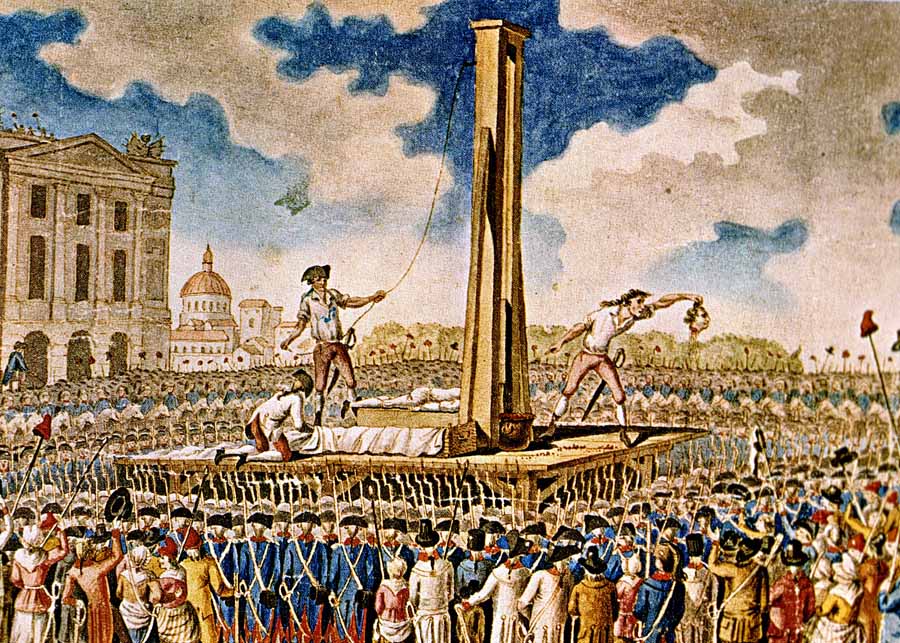

Don K. Preston

Within that Hebraic hermeneutic, just as the Old Testament begins with the primordial origins of the cosmic temple, the New Testament brings the Bible story to a close in the last days of Old Covenant Israel. It was then, in the first century AD, that the Jerusalem temple lost its function as the linchpin of cosmic order in the old heaven and the old earth. The Passion of Christ marked the beginning of a second Exodus, this time with the Sanhedrin playing the role of Pharaoh. The last Adam led his suffering and persecuted people towards a new heaven and new earth. In the Day of the Lord, some forty years later, the Son of Man returned on clouds of glory to destroy the Temple made by hands, replacing it with a heavenly New Jerusalem where God was to dwell forevermore with his people, the spiritual seed of Abraham (Rev. 21:2-3).

Clearly, the apostles placed a distinctively Jewish Christian spin on traditional Hebraic hermeneutics. But there can be no doubt that “Paul’s expectation of the imminent parousia of the Lord is in general to be explained as being in agreement with Palestinian Judaism, or at least some of it”.22 In its simplest form, Jewish eschatology held that the righteous remnant of Old Covenant Israel would be redeemed from the evils of the world by “the Messianic Kingdom that puts an end to this condition”.23 What finally separated Palestinian Judaism from Jewish Christianity was the fall of Jerusalem. First century “Judaism was a God-ordained religion”. Paul and Jesus himself knew well that false Judaizing teachers could continue “to deceive and confuse people as long as the temple existed”. Jewish Christians faced an uphill battle when calling “on the Jews to lay aside Judaism which was given by God and at one time acceptable to God”. The task of the church was simplified “when Jerusalem fell, the temple was destroyed, and [false teachers] could no longer use [the existence of the temple] as a means to confuse people”.24

As Don K. Preston observes, the “relationship of the temple with the identity of the Israel of God can hardly be overemphasized”.25 No Jewish Christian “could view the catastrophe which befell the Jewish state, with its capital and sanctuary, as anything else than the just punishment of the nation for having crucified the Messiah”. Any Jew who accepted that judgement “ceased from that moment to be a Jew; for a Jew who accepted the downfall of his state and temple as a divine dispensation, thereby committed national suicide”.26 The temple was “the symbol of God’s relationship with his people”. God abandoned the temple when that relationship was broken through the martyrdom of the saints and the prophets. The time set for the vindication of the martyrs and for the saints to receive their reward “is the time of the kingdom, the judgment, and the resurrection”. Jesus’ emphatic declaration “that the vindication of all the martyrs was to occur in his generation, in the fall of Jerusalem is a prophecy of unsurpassed eschatological import”27 (Matt. 23:32ff; Rev. 11:15ff). How remarkable then, that Augustine (and the church following in his footsteps) should all but miss “a moment of such radically important, decisive, redemptive historical significance”.28

For Augustine, the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple per se had no special theological significance. Rather, that event was a providential means to an end; namely, the increase of the Church of Christ throughout the whole world. Most Jews were blind to the prophecies of Christ contained in the Hebrew Scriptures. Augustine believed that it was thanks to the fall of Jerusalem and “for the sake of such testimony, which even against their will, they furnish us by having and preserving such books, that [the Jews] are scattered throughout all the nations, wherever the Christian Church spreads”.29 Augustine, of course, knew that Jesus had predicted “the destruction of the earthly Jerusalem” but he insisted that a careful exegesis of the bible would distinguish a local happening of interest only to the Jews from “the end of the world and … the last and great day of judgement”.30

[the second part of this essay will be published tomorrow, noon AEST]

Andrew Fraser was born, raised, and educated in Canada and the United States of America. He taught constitutional law and legal history for many years at Macquarie University, Sydney Australia and is the author of The WASP Question, an inquiry into Anglo-Saxon identity in the context of the modern, globalising world. His Dissident Dispatches is based on his recent experience earning a Bachelor of Theology degree from Charles Sturt University.

Andrew Fraser was born, raised, and educated in Canada and the United States of America. He taught constitutional law and legal history for many years at Macquarie University, Sydney Australia and is the author of The WASP Question, an inquiry into Anglo-Saxon identity in the context of the modern, globalising world. His Dissident Dispatches is based on his recent experience earning a Bachelor of Theology degree from Charles Sturt University.

Endnotes:

- Karl Barth, “The Word of God for the Church,” in G.W. Bromley & T.F. Torrance (eds.) Church Dogmatics Study Edition 1, Pt. 2 (London: T&T Clark, 2009) p. 468.

- Saint Augustine, On Christian Doctrine (Radford, VA: Wilder Publications, 2013) p. 12.

- Denise Kimber Buell, Why This New Race: Ethnic Reasoning in Early Christianity (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005).

- John Milbank, “‘Postmodern Critical Augustinianism’: A Short Summa in Forty Two Responses to Unasked Questions” Modern Theology 7 No. 3 (1991) p. 226.

- John Milbank and Catherine Pickstock, al., Radical Orthodoxy: A New Theology (London: Routledge, 1999).

- John Milbank and Adrian Pabst, The Politics of Virtue: Post-Liberalism and the Human Future (London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016). The phrase “immanentize the eschaton” was coined by Eric Voeglin in his 1952 book, The New Science of Politics.

- Richard Storey, The Uniqueness of Western Law: A Reactionary Manifesto (London: Arktos, 2019) p. 22.

- Alain de Benoist, On Being a Pagan Jon Graham (trans.) (Atlanta, GA: Ultra, 2004) pp. 142-144.

- Storey, cit. p. 22.

- John H. Walton, The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2009) p. 26 (emphasis in original).

- Ibid., p. 28.

- Ibid., pp. 35, 50, 81, 84.

- James Noel Hubler, “Creation ex Nihilo: Matter, Creation, and the Body in Classical and Christian Philosophy Through Aquinas” Scholarly Commons (University of Pennsylvania, 1995) pp. 79, 89.

- See, generally, Steve Mason, “Jews, Judeans, Judaizing, Judaism: Problems of Categorization in Ancient History,” (2007) 38 Journal for the Study of Judaism

- John H. Walton, The Lost World of Adam and Eve: Genesis 2-3 and the Human Origins Debate (Downers Grove IL: IVP Academic, 2015).

- David N. Livingstone, Adam’s Ancestors: Race, Religion & the Politics of Human Origins (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008) p. 5, 26, 33.

- Richard H. Popkin, “The Marrano Theology of Isaac La Peyrère” Studi Internazionali di Filosofia 5 (1973) pp. 97-126; Livingstone, cit. p. 33.

- Livingstone, cit. p. 33-34.

- Peter Enns, The Evolution of Adam: What the Bible Does and Doesn’t Say About Human Origins (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2012) p. 65.

- Ibid., p. 66.

- Ibid.

- P. Sanders, Paul and Palestinian Judaism: A Comparison of Patterns of Religion (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1977) p. 543.

- Albert Schweitzer, quoted ibid., p. 476.

- Franklin Camp, quoted in Don K. Preston, Like Father, Like Son On Clouds of Glory: A Study of the Time and Nature of Christ’s Second Coming (Ardmore, OK: JaDon Management, 2010) p. 153.

- Ibid., p. 153.

- Adolph Harnack, quoted in ibid., p. 154.

- Ibid., 154-156 (emphasis in original).

- C. Sproul, quoted in ibid., p. 154.

- Augustine, The City of God Against the Pagans, R.W.Dyson (ed. & trans.) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), Bk. XVIII, ch. 46-47, pp. 892-894.

- Ibid., Bk. XX, ch. 5, p. 973.

Leave a comment