This article is a response to Dr. Frank Salter’s address to the Sydney Traditionalist Forum, titled “Sir Henry Parkes’s Liberal-Ethnic Nationalism“, which was delivered on 5 December 2020 as part of the Forum’s Quaterly Inquiry Series.

♣

Kinship has historically been weak among Europeans north and west of a line running from Trieste to St. Petersburg. Within that area, and going back at least a millennium, almost everyone was single for at least part of adulthood, with many staying single their entire lives. In addition, children usually left the nuclear family to form new households, and many individuals circulated among unrelated households, often young people sent out as servants. Thus, in comparison to other peoples, northwest Europeans have been more individualistic, less loyal to kin, and more willing to trust strangers.1

These tendencies have a deeper basis. For most, empathy is felt primarily in relationships with loved ones, such as a mother’s relationship with her child. However, research has suggested that those of Northwest European descent are broader in their focus, feeling empathy for anyone they meet—unless they judge that person to be an enemy or a moral outcaste. This universalism extends to their sense of morality, which is less situational and rests more on absolute rules that apply to everyone. Finally, they are more susceptible to obeying such rules and to feeling guilty after breaking them—even if no one else has witnessed the misdeed.2

John Hajnal (b. 1924 d. 2008). See endnote 1 for more information concerning Hajnal’s research and its implications on the “national question”.

Some say this behavioural pattern began with Western Christianity, i.e., what would become Roman Catholicism and, later, Protestantism. By forbidding cousin marriages and by framing morality as a set of universal rules, the Western Church weakened kinship and laid the basis for a new way of organizing society.3 Others say this pattern goes farther back in time; the Western Church thus assimilated pre-existing life-ways from its northwest European converts.4

Whatever the cause, northwest Europeans have been better at creating large social networks independently of kinship. One example is the market economy. Keep in mind the distinction between “market economy” and “markets.” The latter are as old as history, and yet for most of history they were little more than marketplaces—pockets of economic activity limited in time and space, incapable of becoming the main organizing principle of society. That role was played by kinship. Production of goods for a market was secondary to the reproduction of life for family and kin.

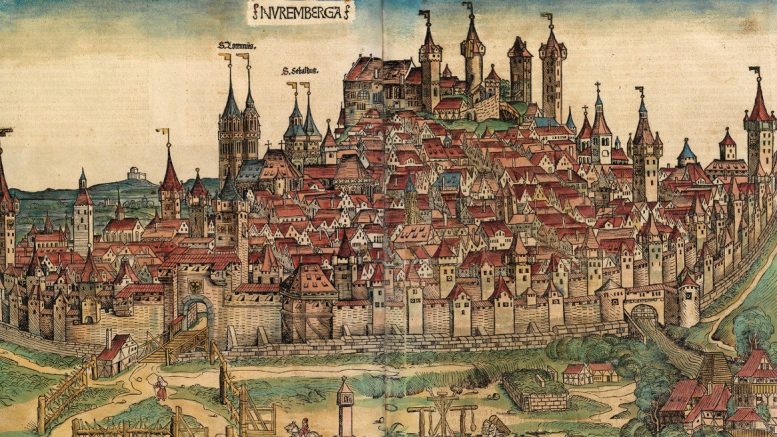

Neither Greece nor Rome created the market economy. That honour goes to the North Sea communities of the seventh century, among whom trade began a sustained expansion that would eclipse trade on the Mediterranean and eventually create today’s global market.5 Tanner Greer pinpoints the fourteenth century as the time when the North Sea economies began to overtake the rest of the world:

[…] the two exceptions are Netherlands and Great Britain. These North Sea economies experienced sustained GDP per capita growth for six straight centuries. The North Sea begins to diverge from the rest of Europe long before the ‘West’ begins its more famous split from ‘the rest.’ […] we can pin point the beginning of this ‘little divergence’ with greater detail. In 1348 Holland’s GDP per capita was $876. England’s was $777. In less than 60 years time Holland’s jumps to $1,245 and England’s to 1090. The North Sea’s revolutionary divergence started at this time.6

The rise of the West has been attributed to the European conquest of the Americas, the invention of printing, the creation of modern financial institutions, the Atlantic slave trade and the Protestant Reformation. Yet, before all of that, the West was already on the rise. The ultimate cause was behavioural: the West was better at expanding the market because it could extend the sphere of high trust far beyond small groups of closely related individuals.

Red indicates the “Hajnal Line”.

The rest is … history. The market economy grew and grew and grew. Initially, its main vehicle was the nation-state; the nations of northwest Europe thus became fierce rivals for commercial dominance. Only later would it free itself from that vehicle, but when exactly? At the dawn of the twentieth century, when the elite of the British Empire became fully global in their ambitions? After the two world wars, which left the United States as the dominant power in the global market? During the 1980s, when offshoring of jobs got into full swing?

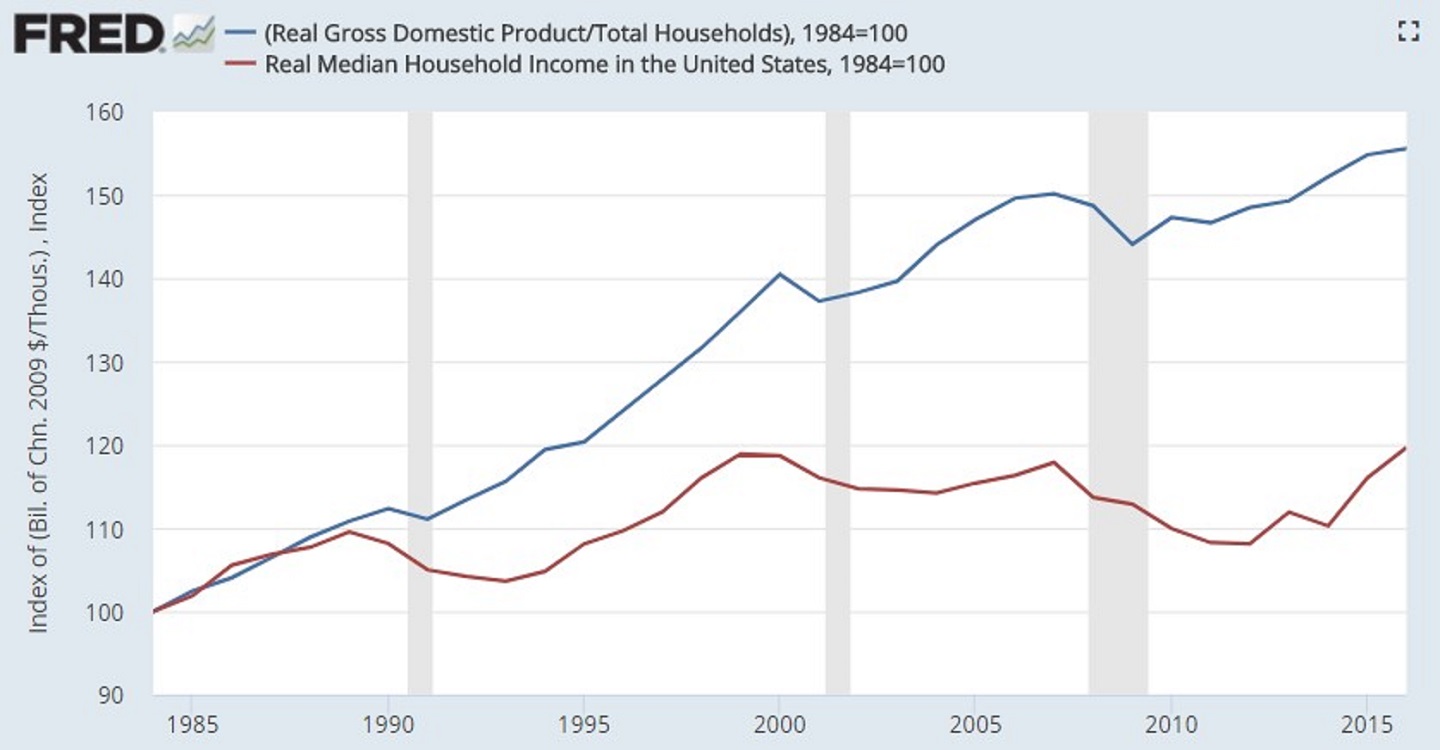

The liquidation of the nation-state was a process, not a point in time. Over the twentieth century our national elites went global and lost any loyalty they once had to the old working class of the West, eventually viewing it as an anachronism. After weighing the costs and benefits, they concluded it should be replaced with cheaper labour from other sources. The old working class has thus been caught in a vice. On the one hand, high-paying jobs are outsourced to low-wage countries; on the other hand, low-wage labour is insourced for jobs that cannot be outsourced, typically in services and construction. The result? Non-elite individuals have seen their wages stagnate throughout the West, particularly in the United States. And the peoples of the West are being progressively replaced, even in their ancestral homelands.

The question we often encounter from status quoists is: so what? Sure, the peoples of the West created the market economy, but that concept no longer belongs exclusively to them and no longer requires their continued existence as a unique or sovereign group. So why should they continue to exist in these terms? That question has two answers:

First, the market economy is more than just a “concept.” It imports certain ways of being. As the demographic and cultural dominance of northwest Europeans dwindles away and eventually disappears, there will be a shift toward behaviours and mindsets that evolved among other groups from other places and times. As a consequence, people will likely become less trusting of each other, less certain about what is expected in terms of social interaction, and less sure about what they “pay for.” Transactions will have to be checked and double-checked, and many will no longer be worth the bother. To keep the market economy from collapsing, governments will become increasingly authoritarian and will adopt Orwellian levels of surveillance.

The second answer is existential. It is the answer that explains every living thing on this planet. We were. We are. We will be. Existence is not justified by argument. It is justified by an act of will.

Frank Salter and the National Question

Frank Salter is probably best known for his book On Genetic Interests: Family, Ethnicity and Humanity in an Age of Mass Migration (2003). Recently, he has argued for a new balance between the market economy and the need for kinship. This balance would be provided by “national liberalism,” as defined by the nineteenth-century thinker John Stuart Mill:

Where the sentiment of nationality exists in any force, there is a prima facie case for uniting all the members of the nationality under the same government, and a government to themselves apart […] One hardly knows what any division of the human race should be free to do if not to determine with which of the various collective bodies they choose to associate themselves.7

John Stuart Mill (b. 1806 d. 1873)

This twinning of nationalism with liberalism was common during the nineteenth century. Liberals saw the nation-state as a means to emancipate the individual from the confines of local and regional identities. France was the go-to model. Originally, its people mostly spoke various regional languages; only a minority could speak French. Even the laws differed from one part of the country to the other. After the Revolution, a uniform language was imposed through the schools, and the laws too were made uniform. Individuals could now freely circulate and express themselves within a much larger territory. There were also economic benefits: economies of scale, labour mobility and a more rational distribution of the factors of production.

That logic, however, did not stop with liberal nationalism. It eventually led to globalism. The latter is often viewed as a healthy reaction to the sins of the nation-state, particularly the two world wars, yet nationalism was already morphing into globalism before 1914. Look at John Stuart Mill’s own country. In the early nineteenth century it was, arguably, a nation-state. Most people under British rule were of British origin and shared a common culture and identity. All of that would change as the century progressed: the British became a minority within a vast multinational empire. The country no longer served its people and their desire to perpetuate themselves. It now served the global ambitions of its elite.

As Frank Salter points out, nationalism can be diverted into other channels. Modern techniques of propaganda can create an artificial feeling of kinship that serves elite interests:

[…] investment in ethnic kin carries risks due to reliance on culture, which is more prone to error than the instinct-laden bonds of family. In his book, Imagined Communities, the Marxist historian Benedict Anderson argued convincingly that national communities are perceived indirectly through cultural channels, such as stories, books, films, press reports, memorials, and so on. The same goes for events that are perceived to enhance or threaten the nation. The sense of fellowship can be extended through cultural devices to elicit bonding with hypothetical kin. Likewise, the realm of antagonisms, of distrust, hatred and combat, can be hugely inflated in scope and intensity in the ethnocentric mind.8

Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada (b. 1919 d. 2000)

The risks are obvious. The national elite may pursue their self-interest to the detriment of the nation they supposedly serve. Instead of using their cultural dominance to promote national aims, they may manipulate the culture to further their post-national and supra-national ambitions.

This problem was noted by Pierre Elliott Trudeau, when writing in 1948 about Canada’s conscription crisis a few years earlier. Elites may be inevitable, but their survival is not; it is thus in their interest to defend the interests of their host society.

Thus our leaders believed in government of the people, for the people, but not by the people. They nursed a secret thought that the people can err, that the elite’s duty is to save this formless mass that is led by passion rather than reason, and which may not want to be saved [malgré elle]. Certainly, there are things to say in favour of that theory, which is called elite theory, and against the convention that 51% of the population always has a monopoly on wisdom. But we could not help but be astonished that we were being called up to serve under the flag (God knows which one!) precisely to fight theories in other places that were being brazenly applied at home. And we had to conclude that our “elite” were seeking to save by force of arms something else than democracy, and perhaps something less honourable.9

Today, his son proudly describes Canada as the world’s first post-national state. Yet the problem remains. If there no longer is a nation, and if our elite no longer serve their “fellow Canadians,” whom do they serve? Good people everywhere? The reality is a little less noble. They largely serve themselves and their self-centred worldview.

Gross Domestic Product compared to Mean Household Income in the United States – when did the interests of the elites diverge from the people? (Image: Wikicommons)

— Peter Frost is a Canadian anthropologist who earned his doctorate at the Université Laval in 1995 and has been widely published in peer reviewed journals such as the Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology, the International Journal of Circumpolar Health and Evolution and Human Behaviour.

Endnotes:

- Peter Frost, “The Hajnal Line and Gene-culture Coevolution in Northwest Europe” Advances in Anthropology 7(3) (2017) pp. 154-174; Peter Frost, “The Large Society Problem in Northwest Europe and East Asia” Advances in Anthropology 10(3) (2020) pp. 214-134; John Hajnal, “European Marriage Pattern in Perspective” D.V. Glass and D.E.C. Eversley (eds.) Population in History. Essays in Historical Demography (London: Arnold, 1965); M. S. Hartman, The Household and the Making of History. A Subversive View of the Western Past (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004); “HBD Chick” (pseudonym) “Big Summary Post on the Hajnal Line” HBD Chick (blog) (10 March 2014) <hbdchick.wordpress.com> (accessed, 30 December 2020); A. Macfarlane, The Origins of English Individualism: The Family, Property and Social Transition (Oxford: Blackwell, 1978); J.F. Schulz, D. Bahrami-Rad, J.P. Beauchamp, and J. Henrich, “The Church, Intensive Kinship, and Global Psychological Variation” Science 366 (707) (2019) pp. 1-12; W. Seccombe, A Millennium of Family Change. Feudalism to Capitalism in Northwestern Europe (London: Verso, 1992) pp. 94-95, 150-153, 184-190.

- Frost ibid. (2017); Frost ibid. (2020); Schulz et al. ibid. (2019).

- “HBD Chick” op. cit. (2014); Schulz et al. ibid. (2019).

- Frost op. cit. (2017); Frost op. cit. (2020).

- H. Barrett, A.M. Locker and C.M. Roberts, “Dark Age Economics Revisited: The English Fish Bone Evidence AD 600-1600” Antiquity 78 (301) (2004) pp. 618-636; J. Callmer, “North-European Trading Centres and the Early Medieval Craftsman. Craftsmen at Åhus, North-Eastern Scania, Sweden ca. AD 750-850+” UppSkrastudier 6 (2002) (Acta Archaeologica Lundensia Ser. 8, No. 39) pp. 133-158.

- Tanner Greer, “Another Look at the ‘Rise of the West’ – but with Better Numbers” The Scholar’s Stage (blog) (20 November 2013) <scholars-stage.blogspot.ca> (accessed, 19 January 2021); See also: Tanner Greer, “The Rise of the West: Asking the Right Questions” The Scholar’s Stage (blog) (7 July 2013) <scholars-stage.blogspot.ca> (accessed, 19 January 2021); “HBD Chick” (pseudonym) “Going Dutch” HBD Chick (blog) (29 November 2013) <hbdchick.wordpress.com> (accessed, 30 December 2020).

- Cited in: Frank Salter, “Sir Henry Parkes’s Liberal-ethnic Nationalism” SydneyTrads – Weblog of the Sydney Traditionalist Forum (blog) (18 December 2020) <sydneytrads.com> (accessed, 30 December 2021) ¶ 17.

- Ibid. ¶ 27.

- Pierre Elliott Trudeau, “Réflexions sur une démocratie et sa variante. Lettre de Londres” Notre Temps. Hebdomadaire Social et Culturel 3 (18) (14 February 1948) pp. 1, 6.

Be the first to comment on "The National Question (A Response to Frank Salter)"