When I look back on my life in Australia, I feel truly grateful for the education which I received, and which forms an integral part of my identity. I am one of the fortunate souls who received a complete, traditional, private-school education, which, I believe, has sadly become almost extinct in the Western world today.

I was born in 1971 and started primary school in 1976 in Sydney Australia. I attended first a co-educational Catholic school and then, in 1981 a private all-boys’ Anglican school from year four until my Higher School Certificate in 1989. I give you these dates for a reason, dear readers: for this period of time marks the end of the era of traditional education, not only in Australia, but in most of the world.

At school, I was educated not only in all the core subjects of English, Mathematics, Science and History, but also in religion, physical education, European foreign languages and good manners. This is in sharp contrast to the secular public school education system, which focuses on “feel-good” subjects like environmentalism, “texts” rather than literature (in which a “text” can include a box of cereal or a train ticket) and student-centred learning. Instead of pupils (rather than “students”) sitting quietly and politely in rows listening to the teacher impart knowledge while they take notes, complete exercises and ask questions, they now sit in small groups and work by themselves, with little or no help from the teacher, whose role is now reduced to that of “facilitator”, or “trainer”. I have spoken to students at university and even so-called educators who display a gross ignorance in matters of Judeo-Christian culture and history and grammar. In fact, during my teacher training, I was often called upon, and I still am today, to explain matters of grammar and pronunciation to my colleagues. Sadly, many of my contemporaries and their children belong to what I call “the Culturally Stolen Generation”!

Unlike many schools today, ours taught us to respect our elders and superiors, to wait for teachers outside the class, to stand for teachers who enter the room, to wait for teachers to dismiss us, to raise our hats (yes, hats were part of our uniform) to ladies, and to address gentlemen as “sir” and ladies as “Madam” or “Ma’am”.

In our school, we had an assembly every morning in which our headmaster addressed all the pupils after a prayer and some hymns. In some assemblies, we sang the national anthem of the time, which was “God save the Queen” until “Advance Australia Fair” replaced it (in 1984, and we still sang both together for another few years).

In English classes, we learned English grammar, vocabulary and spelling, we practised our handwriting, and we studied the best literature, which included works by John Donne, William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, Jane Austen, William Golding and George Orwell, among others. We read books and wrote all of our assignments by hand, on paper. We also sat for all of our examinations using pen and paper. Only at university did we start using a typewriter. We could not imagine the existence of the Internet or mobile telephones. Computers existed, but their uses and functions were limited.

Let it be known to my dear readers that I have nothing at all against computers per se but to the addiction to them, and total dependence upon them, which is evident in young people today. I know several children of this generation, the offspring of my friends and relatives, who seem unable to function without electronic devices. I more often than not see them with wires attached to their ears and their eyes glued to a small screen. This is the deplorable condition to which I was fortunately not exposed as a young man. Certainly, we had computer games of various sizes, but our parents limited our usage of them, and made sure that we balanced computer usage with outside play and intellectual development. Parents seem to be unwilling or perhaps unable to do this today.

Let me reiterate: there is absolutely nothing wrong with using the Internet to do extensive research, for which we needed about fifty volumes of the Encyclopaedia Britannica in the past. Nor is there anything wrong with shopping online, with using Skype to talk to friends and family overseas, using a hand-held mobile telephone to take photographs or using CD-ROMs or You-Tube to learn the lyrics of songs or even learn a new language. I do however find it objectionable that young people spend hours “chatting” electronically with friends who live in the same town, instead of going out to meet them or talking to them on the telephone; or even worse, that they chat to strangers who could turn out to be predators, as the daily news sadly reports every now and then. I also find it sad and frustrating that electronic devices and machines are replacing human beings in the supermarket, on the telephone and in society in general (e.g. self-service cashiers, ATMs, recorded telephone menus).

When we were growing up, the world was a safer and friendlier place. There was little or no threat of terrorism, urban crime was minimal, neighbours talked to each other, and children generally respected their elders. In those days, compared to what children as young as ten know nowadays, my friends and I remained relatively innocent until we completed high school. I cannot of course speak for every single school pupil, but my friends and I rarely if ever discussed pedophilia, the political left-wing agenda, feminism, homosexuality and violent crimes such as home invasions and drive-by shootings. Was that because these phenomena were rarer in those days or because we were sheltered from them, or both? We certainly did not have twenty-four hour access to the news on mobiles and on the Internet as we do now, so it is difficult to tell. Suffice it to say that we enjoyed an innocence that has almost become extinct even among the pre-pubescents of today.

Since I started my education in the 1970s and 1980s, the feminist occupation and sabotage of our language had not yet gained momentum, and we could still use traditionally generic masculine terms like “man”, “mankind” “chairman” etc. and use the masculine pronoun generically to include both men and women. At that time, the first line of the national anthem was still “Australia’s sons let us rejoice…”, and I can distinctly remember my headmaster justifying this generic use. Political correctness was slowly taking a stranglehold of the language, but it started to make its ugly presence felt when I reached university. I can still remember being able to use the words “gay”, “queer”, “chairman”, “sex” (meaning what is now called “gender”) in their original meanings during the early 80s without objection, apart from a few puerile giggles.

In our school, as in many others at the time, we still had both corporal and psychological punishment, and discipline was maintained to preserve order and dignity in the school at all times. The teachers still had all the power, and pupils had to respect and obey them, otherwise they might face suspension or expulsion. Pupils could be punished for truancy (unexplained absence without a medical certificate), lying, talking in class while the teacher was talking, swearing, littering, violence, bullying, stealing, indecent behavior, tardiness, failure to complete homework and many other misdemeanours.

Nowadays, I hear from my friends’ children about gang-fights in schools, pupils terrorizing teachers by throwing objects at them or by damaging their vehicles, teachers receiving death threats (this happened to one of my friends who worked in a public school in a rough neighbourhood not long ago), and many other incidents which prove that it is the pupils who control the teachers. It would surprise me if they actually learned something during all this savagery.

In my current profession, I come into daily contact with refugees and migrants from Asian and Middle-Eastern countries, and they often ask in wonder about the lack of rigour and discipline in their children’s schools. A lot of them complain that their children are not learning much, or learning the wrong things (e.g. about “tolerance”, “diversity”, sexual freedom, their “right” to call the police if their parents administer corporal punishment etc.). I learn from them that even today, the teachers in their countries are mostly respected, or at least feared, and that the system is merciless on truancy, laziness and disrespect. I am not advocating that we adopt all the draconian measures employed in the Middle-East and Asia, but we can learn from them their respect for education and teachers. Furthermore, there must be something terribly wrong with an education system which produces teachers who are sometimes corrected in their grammar by these migrants educated in traditional schools and by traditional methods. I have witnessed this phenomenon several times during my career.

In conclusion, when I consider the youth of this generation and the sexually saturated and hostile politically correct atmosphere in which they now struggle to breathe, I feel truly grateful for the excellent education that I received and I pray that one day, we shall return to the good old traditional education that I once enjoyed, even with the assistance of technology.

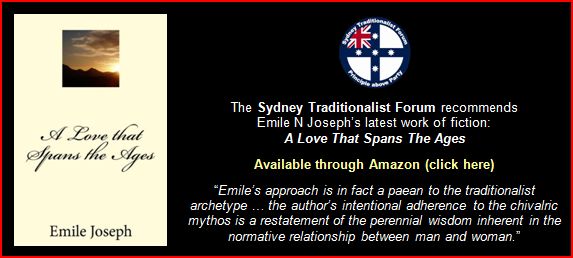

– Emile N Joseph

The author teaches the English language to adult migrants and is passionate about all things linguistic. He is also a serious conservative at heart, who treasures the beauty, the poetry and the gallantry of yesteryear. He is happily married with two young children in Sydney.

Be the first to comment on "My Education in Australia"