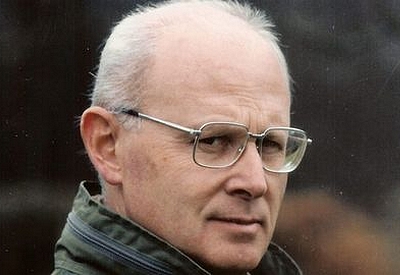

Dominique Venner (born 16 April 1935) ended his life publicly and dramatically by shooting himself in the mouth before the altar of Our Lady of Notre Dame in Paris three years ago on 21 May 2013. The bullet passed through Venner’s brain and exited the back of his head. In the opening paragraph of a suicide note that he sent to his publisher, Venner sought to justify his action:

I am healthy in body and mind, and I am filled with love for my wife and children. I love life and expect nothing beyond, if not the perpetuation of my race and my mind. However, in the evening of my life, facing immense dangers to my French and European homeland, I feel the duty to act as long as I still have strength. I believe it necessary to sacrifice myself to break the lethargy that plagues us. I give up what life remains to me in order to protest and to found. I chose a highly symbolic place, the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris, which I respect and admire: She was built by the genius of my ancestors on the site of cults still more ancient, recalling our immemorial origins.1

Guillaume Faye (b. 1949)

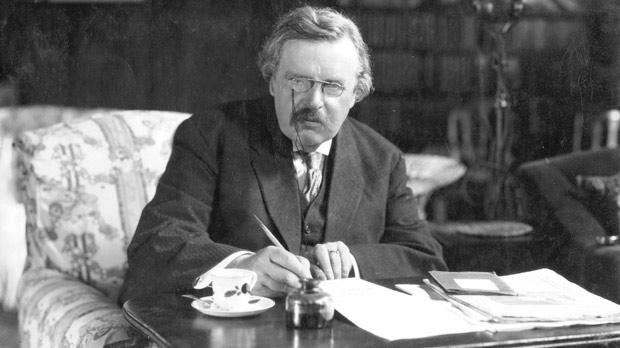

A reader cannot avoid remarking the contradictoriness of Venner’s testament. A professed love of life comports itself awkwardly with a gesture of self-annihilation. One could argue that Venner meant by “life,” not his own, but the collective, trans-personal vitality of his children and their descendants; he refers after all to “the perpetuation of [his] race and [his] mind.” Seen in that way, the suicide might rise to being a Stoical demonstration, like those of Petronius and Seneca in the time of Nero. Even so, no few problems remain; not least the disrelation between Venner’s professed respect and admiration for the “highly symbolic place” of the Lady Church and his having blemished its consecrated precincts with his effluvia. How moreover would such an act “break the lethargy that plagues us”? More likely – even patently, looking back on the event – it would merely add to the pernicious confusion of the times. The explanation of these contradictions is undoubtedly linked to the fact that while Venner acknowledged his belonging to a specifically Christian civilization in its late phase, he never himself identified as an adherent of that faith. Like his countrymen-contemporaries Guillaume Faye (b. 1949) and Alain de Benoist (b. 1943), Venner espoused Friedrich Nietzsche’s Neo-Pagan view of Christianity as “slave morality,” a religion of defeat and death, and the cause rather than the antidote to the malaise of modernity unleashed.

Like Nietzsche, whom Venner admired, and who signed his last letters as “The Crucified One,” the suicide might well have been experiencing a revilement of Christ which was, at the same time, a desire to rival and replace Him. That would account for Venner’s characterization of his act as an instance of “self-sacrifice” and for his references to “cults still more ancient” than the Cult of the Virgin on the Ile de la Cité, with whose pre-Christian religiosity he would have identified in opposition to Christianity.

Alain de Benoist (b. 1943)

Despite all that, adherents and defenders of Christian civilization – or of a less creedal, “perennial” Tradition – will assuredly find in Venner’s suicide note a number of pithy assertions with which they concur. Venner’s view of the reigning cultural degeneracy, for example, corresponds largely to theirs. Venner writes of his “protest against poisons of the soul and the desires of invasive individuals to destroy the anchors of our identity, including the family, the intimate basis of our multi-millennial civilization.” While invoking a type of cultural relativism, Venner nevertheless attests on behalf of a properly European culture that stands in rightful vigilance over its integrity. “While I defend the identity of all peoples in their homes,” as Venner writes, “I also rebel against the crime of the replacement of our people.” The word “crime” is strong enough to underscore itself. Claiming the absence of any “identitarian religion,” Venner emphasizes as the basis of Western consciousness what he calls “a common memory going back to Homer,” which he describes as “a repository of all the values on which our future rebirth will be founded once we break with the metaphysics of the unlimited, the baleful source of all modern excesses.” Christians and Traditionalists will recognize themselves in that pronouncement too, with its call for limitation rather than do-what-you-will. In a final sentence Venner hopes that his friends and survivors will find “in my recent writings intimations and explanations of my actions.”

Defenders of Christian civilization and Traditionalists alike will point out that Christianity is nothing if not the historical “identitarian religion” of Europe, and that if modern people in their numbers had abandoned the Church the fault would lie with them at least as much as with the Church. In addition there is the fact that the High Medieval religiosity of Europe was a mélange of Pagan and Christian themes. The authors of the Grail Romances never ceased being Christian simply because they worked with mythic materials endowed on posterity by Celtic heathendom. Nor did Sandro Botticelli ever cease being Christian simply because he painted a startling Venus borne aloft from the seawaves on a fantastic scallop. Medieval zealots of the Church might have tried to extirpate vestiges of paganism, something concerning which Venner once issued a complaint, but the historical point is that the zealots failed. The Renaissance offers itself as the proof. While making the objections and pointing to the errors, Venner’s fideistic critics must yet acknowledge that, beyond its sniping and rather adolescent treatment of Christianity, Venner’s work, if not precisely the man himself, remains valuable to them – more valuable, say, than the work of Faye and Benoist, the considerable value of their work notwithstanding. In the aftermath of Venner’s death, his work bears re-examination, not least because his life implicates the late Twentieth Century and its continuation in the Twenty-First.

Friedrich Nietzsche (b. 1844 d. 1900)

Venner himself took on the role of chief recorder of his life. Many of his books and even his oeuvre taken whole run to the autobiographical. A scrupulous reading must keep in mind then that Venner the subject plays Boswell to his own Johnson and that investigators therefore receive only a carefully controlled version of events. Yet he appears to hide nothing. He is frank about his participation in the Organisation de l’armée secrète in 1961, his subsequent conviction in a military court for crimes pertaining to his participation, and his eighteen-month sentence. Some OAS members received death-sentences and gave up their ghosts before a firing squad. The most famous living survivor of the OAS after Venner’s death is Jean-Marie Le Pen, founder of Le Front National and the father of Marine Le Pen. Concerning the OAS, in the autobiographical Shock of History (English translation 2015), Venner answers his interlocutor, Pauline LeComte, unrepentantly: “After two years of [army] service in Algeria, I wanted to continue the fight in the world of political agitation. I became convinced that the fate of Algeria would not be decided on the battlefield, but in Paris.”2 As Venner puts it, he helped to organize “a small political Free Corps that sought a kind of nationalist revolution.”3 The OAS sought to realize a coup-d’état against General De Gaulle’s Fourth Republic. On release from prison, Venner immediately re-entered politics, founding the group Action Europe, to which, he claims, “the New Right… owes of much its intellectual structure.”4

Venner’s penchant for action, including a willingness to resort to armed violence, finds reflection in his gallery of heroes. Whom did Venner venerate? In Chapter 4 of Shock, “Hidden Heroic Europe,” Venner addresses the case of Claus von Stauffenberg, the would-be assassin of Adolf Hitler and the leading light of a failed coup-d’état against the Reich. Venner asserts Stauffenberg to have been, not only “the most unwavering of Hitler’s adversaries,” but also a man of “high-born and noble” character who “believed that certain elite men were appointed to accomplish noble things.”5 In Venner’s description of the Valkyrie conspiracy, readers will detect its anticipatory parallelism, in Venner’s mind, with his own conspiratorial activity against the Fourth Republic. Venner reminds LeComte that Stauffenberg stemmed from the Swabian nobility and that among his motives his intense nationalism figured importantly. Venner reasonably rejects the notion that Stauffenberg acted in order to placate the “two Anglo-Saxon Thalassocracies.”6 Stauffenberg never, in fact, planned to dismantle the Reich; he wanted rather to purge it of National Socialism, while retaining the institutions of the Prussian State. Venner also remarks that Stauffenberg was an educated man who admired the Greeks and Romans and professed his admiration for Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, a statement that would assimilate the two men.

Oberst Claus von Stauffenberg (b. 1907 d. 1944)

One recalls the references to “a common memory going back to Homer” in the suicide note. One recalls also the reference to “cults still more ancient,” hence pre-Christian, hence legitimate where Christianity is not, in the same source. Did Venner think that his act would stimulate a revival of such religiosity? If so, it would be flawed thinking, as most modern people have no religiosity whatever and are unlikely to respond to esoteric cues.

Consider, finally, what Venner observes regarding Stauffenberg’s moral resolution: He carried out his part in the Valkyrie conspiracy despite his realistic assessment that the plan would probably fail. Stauffenberg was, as Venner puts it, “on a crucial mission of regeneration” for Germany; despite his failure to realize his aim, Stauffenberg’s “act of sacrifice on 20 July 1944 served to cleanse the German people from the blemish of the Führer’s regime.”7 Notice, however, what Venner omits to say about Stauffenberg: Namely that the officer and nobleman continued to be a practicing Catholic all his life. That is a blatant omission, even more so in that Venner rehearses the facts about Stauffenberg and Valkyrie for over a dozen pages. In Stauffenberg’s manifesto – which Venner quotes in full – readers will come across this sentence: “We [the conspirators] recognize the great traditions of our Western culture, a coalescence of Hellenic and Christian origins.”8 Venner makes no comment (the quotation of the manifesto in full concludes the chapter), but the reader is left wondering how he might have assimilated Stauffenberg’s recognition. He probably could not have done it. Not incidentally, another supporter of Valkyrie, General Erwin Rommel, also like Stauffenberg remained religiously active, in his case as an Evangelical Lutheran. Stauffenberg did not become a suicide: His executioners stood him against a wall and shot him. Rommel indeed resorted to suicide: With the Gestapo surrounding his house, he first conferred with his eldest son, and then retired to his study to end his life with a pistol-shot. Venner sides with Stauffenberg against Hitler’s Reich, but Stauffenberg opposed Hitler’s Reich in part because it was an atheistic-totalitarian polity that sought to subdue and abolish Christianity.

Field Marshall Gen. Erwin Rommel (b. 1891 d. 1944)

It is worth sorting out the differences further. When Venner killed himself he was not, as far as anyone knows, under external duress, but Rommel, whom Venner never mentions in The Shock, emphatically was. Venner’s hero Stauffenberg died by firing squad, not by his own hand. Venner, perhaps rightly, describes Stauffenberg’s death as a purifying “sacrifice,” the same description that he applies to his own suicide in advance. The description certainly gains plausibility in reference to Stauffenberg, but not so much in reference to Venner. The function of the description would once again be to assimilate the two men, to Venner’s benefit, but the gesture can only effectuate itself through the omission of Stauffenberg’s Catholicism. Venner rejects Christianity, including Catholicism, on Nietzsche’s arguments. Neither Stauffenberg nor Rommel subscribed to Nietzsche, but both practiced the Christian faith. Rommel’s suicide explains itself, and commands respect, in a way that Venner’s suicide cannot. Among Rommel’s motives, protecting his family from associative retribution by an enraged power must have figured largely; his act thus recommends itself as a grim concession to his wicked enemies, who, wicked though they were, indeed accepted the concession and left the family unmolested. Rommel’s wager proved its rationality in its sequel.

Venner could stake a claim to no such motive as Rommel’s; and whether or not he had arranged for the welfare of his family, his act invites assessment as grossly privative and not a little bit nihilistic. Nor can Venner be said to have proven anything through his self-annihilation. On these accounts, then, wisdom must doubt that the suicide had any solid moral or intellectual motivation and it must judge that the act’s incoherence matches the incoherence that Venner himself saw in the modern condition.

The chapter of The Shock that follows “Hidden Heroic Europe” bears the title “In the Face of Death.” This chapter concerns itself with the “tradition of voluntary death.”9 Returning to the theme of Stauffenberg’s death, Venner characterizes it anew as, “not strictly speaking, a suicide, but… certainly not far removed.”10 Facing death, Stauffenberg “had finally become the hero he had dreamt of becoming,” and he thereby “in a self-sacrificial manner” achieved his goal “to leave a mark on history.”11 Stauffenberg thus resembles the heroes of the Trojan War, to whom the oracles of the gods had vouchsafed knowledge of imminent death in battle, but who battled with courage despite that knowledge in order to achieve quasi-immortality in the proper heroic cults that would survive them. Strictly speaking, however, such deaths are not suicides. Venner writes that Catholicism “has condemned suicide since Saint Augustine, who was simply repeating metaphysical arguments developed by Plato”; on the other hand, “the stoic tradition of Rome held [suicide] in high regard, and has offered a number of exceptionally heroic examples.”12 He gives the Roman instances of Lucretia, Cato, and the Prefect Publius Spendius under the reign of Caracalla, but he omits Seneca and Petronius. Among the Greeks he mentions Empedocles, who legendarily threw himself into the crater of Aetna.

Yukio Mishima (b. 1925 d. 1970)

Among the moderns, Venner feels the attraction of Yukio Mishima, in whose Bushido discipline he undoubtedly saw another reflection of himself. He feels likewise the attraction of Henry de Montherlant, a writer, who, in 1972, “threatened with the prospect of becoming blind and refusing to endure such a fate… took a handgun and [he] shot himself in the head.”13 While reasonable people will understand, although not necessarily validate, Montherlant’s lethal choice, Mishima’s elaborate public suicide, like Venner’s, has about it the taint of a sordid exhibitionism. Perhaps it was coherent in a Japanese context, but Venner was French, not Japanese.

The themes of human sacrifice and human self-sacrifice belong, first of all, to prehistoric and antique religion. When human sacrifice began to constitute a moral embarrassment to civilized people, suicidal self-immolation or self-banishment could partly substitute for its removal by duplicating its function. The action of Oedipus Rex would hardly be tragic if Sophocles had made his Thebans to solve their problem modo grosso by forming a mob and lynching their suddenly troublesome monarch. Rather in Sophocles’ drama, Oedipus is made decorously to self-blind and self-exile for the sake of his city, Thebes, which is thereby purified. (Meanwhile Queen Jocasta kills herself offstage.) In the sequel, Oedipus at Colonnus, with Athens and Thebes fighting over the blind vagrant who has now become a living oracle, and thus a coveted asset, the self-exile undergoes apotheosis in a flash of light that removes him from the mortal realm. In discussing a similar apotheosis said to have befallen Romulus at the end of his kingship, Livy remarks that that is the story, but he immediately adds that not a few rationalists suggest that the Senate, growing annoyed at the king’s increasing despotism, formed a mob and did away with him in a kind of Dionysiac sparagmos.

René Girard (b. 1923 d. 2015)

The probable sacrifice of Romulus establishes the real beginning of the Roman Republic, just as the highly sacrificial murder of Julius Caesar in the foyer of the Senate establishes the real beginning of the Roman Empire. Romans of the Imperial centuries disdained human sacrifice in principle, but they ruthlessly executed criminals and dissidents in public and enjoyed blood-sport as entertainment. Venner seems unaware of this aspect of antique society, or if he were aware of it, he would have deliberately elided it.

It will be useful at this point to invoke another countryman-contemporary of Venner, the late René Girard (1923 – 2015), who left France for the United States in the 1947, became a naturalized citizen, and worked his way up to a professorship at Stanford that he held for four decades. Modern people might have learned from the work of Girard, if they had ever bothered to read him, that, however great Classical Antiquity was, especially in the form of the Roman Empire, it had its social organizing principle in sacrifice, including blatant and, latterly, surreptitious human sacrifice. In Girard’s interpretation, massively argued in a fifty-year archive of books, articles, and interviews, Christianity takes a unique place among religions in that it rejects and anathematizes sacrifice. Christianity anathematizes suicide because, quite as Venner himself argues, the circles of suicide and sacrifice blend together in the diagram and become confused. Even respecting fatal martyrdom, Christian authorities, especially in the Greek-speaking East, discouraged it. The martyrs of the arenas in Rome and elsewhere were sacrificial victims, but not of Christianity; rather, of the Imperial state. The Christian Roman Empire committed in its turn many moral enormities, beginning under the reign of Theodosius I, with a ramping-up under Justinian, two nominally Christian emperors who behaved more like Caliphs than like Christians.

Under Christianity, however, gladiatorial exhibitions came under a ban – a moral advance, certainly, for humanity – and the family, which Venner extols, and which had fallen into decadence in Paganism’s late phase, enjoyed reinvigoration. Under the Christian dispensation, Europe would see the gradual disappearance of slavery, here and there by simple abandonment of the institution, but elsewhere by legal abolition. The medieval peasants were not slaves although they are often made to appear so in fatuous modern representations of the era.

Gregory of Tours

When Venner condemns Christianity, his condemnation justly applies to Theodosius, Justinian, and those like them who have interpreted the Gospel the way that Muslims interpret the Koran and whose internal crusades against heretics and Pagans anticipated jihad. Venner’s condemnation also justly applies to those medieval clerics against whom, for their zealous attempts to extirpate every last vestige of Paganism, he lavishes no little ire in his Histoire et Tradition des Européens (2002), the grand summation of his thinking. Venner writes in the chapter concerning “Nihilisme et saccage de la Nature,” of a rupture of man from nature that occurred in the early medieval centuries as Christianity replaced and then attempted to suppress the immemorial cults of Pagan localism in Europe. In Venner’s words, “Having adopted [the Biblical] God… having made of him a universal deity, transplanted out of his native habitat, nascent Christianity took over his roster of anathemas.”14 Venner quotes Gregory of Tours as “thundering against the Franks”15 because of their insistence on maintaining their forest altars. For some among the clerisy, the nature-spirits had become hellish imps deserving only of exorcism. At the same time, Venner sees what he calls “the resistance [résistance] of the medieval forest divinities,”16 that is to say, the stubbornness of the people concerning their cults. Seeing in the High-Medieval iconography of the cathedrals a resumption of Neolithic animal-imagery and identifying that imagery with the nature-spirits of the cults, Venner remarks that, “Beyond the Eleventh Century of our era, animals again find themselves frequently represented in religious statuary.”17

Venner’s word-choice of résistance endows itself with an abundance of connotations relevant to his own case. In endorsing that résistance retroactively Venner declares himself a Nineteenth Century Romantic in the line of Alfred de Vigny, Alphonse de Lamartine, and Victor Hugo. He would also align himself with the English and German Romantics of the same period. The difference between Venner and the Romantics is that while they cherished in the Middle-Ages the same vestiges of Paganism as did Venner, they never, as Venner does, rejected the Christian content of that historical period. They could see the Western Tradition as having nurtured a startling synthesis. When the Romantics defended old customs and conventions, they were defending the synthesis of them with the Gospel against a new materialistic and positivistic order that was vehemently inimical to any spiritual value or perception, whether Christian or Pagan. Almost everywhere in his work, Venner remains blind to that aspect of Christianity which not only could, but did, find a way to meld itself with what was redeemable in Paganism. Whereas contemporary environmentalism, for example, suffers distortion under ideological influence, it nevertheless reflects a sense of nature that can trace itself back through Romantic sensibility to the ethos of Francis of Assisi’s canticle “Brother Sun and Sister Moon” and behind that to a combination of the Pagan sense of genius loci and the philosophical pantheism of Late Antiquity.

Let it only be noted that neither St. Francis nor the philosophical pantheists ever sacrificed anything to les divinités sylvestres. Venner has a thing about Christianity, undoubtedly, which results an unfortunate tendency in his discourse.

[Part II (Scheduled for 3 XI 2016)]

Prof. Thomas Bertonneau

– Thomas F. Bertonneau is an American intellectual and professor. He has taught at a variety of institutions, and has been a member of the English Faculty at State University of New York, Oswego, since 2001. His articles and essays have appeared in a diverse array of scholarly journals including William Carlos Williams Review, Wallace Stevens Journal, Studies in American Jewish Literature, North Dakota Quarterly, Michigan Academician, Paroles Gelées: UCLA French Studies, and Profils Americains. He was a major contributor to the English section of The Brussels Journal. More recently, his work has appeared in The University Bookman, the John William Pope Center for Higher Education Policy as well as the websites The People of Shambhala and The Orthosphere. He has also contributed to the Symposia of the Sydney traditionalist Forum.

Endnotes:

- Dominique Venner, “The Reasons for a Voluntary Death” Greg Johnson (trans.) Counter Currents Publishing (blog) (May 2013) <counter-currents.com> (accessed 29 October 2016) republished by Alfred W Clarke, Occam’s Razor (blog) (22 May 2013) <occamsrazormag.wordpress.com> (accessed 29 October 2016).

- Dominique Venner, The Shock of History: Religion, Memory, Identity, Charlie Wilson (trans.) (London: Arktos, 2015) p. 11.

- Ibid. p. 11.

- Ibid. p. 12.

- Ibid. p. 33.

- Ibid. p. 35.

- Ibid. p. 43.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. p. 44.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. p. 45.

- Ibid. p. 51.

- Dominique Venner, Histoire et Tradition des Européens: 30,000 ans d’identité (Monaco: Editions du Rocher, 2011) p. 232. The writer’s translation, as hereafter, with assistance from “Tiberge”.

- Ibid. p. 232.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. p. 231.

Leave a comment