Strategic Considerations for

Anglo-Australian Identitarians

Abstract

This paper argues that Anglo patriots should use a dual political-cultural strategy to defend the historic Australian nation and reestablish the liberal nationalist state built by the founders. The recent success of nationalist protest parties in many Western societies, including Australia, indicates that voters are ready to confer significant political and cultural niches on leaders who are willing to challenge the dominant culture. There are ways forward.

Contents

| Part 1 (click here to return) | Part 2 (appears on this page) |

| I. Introduction: Goals & winning conditions II. Political activism III. Cultural activism IV. Feedback: the virtuous cycle (a) Multiculturalism (b) Risks of feedback (c) Personal activism V. Choosing a nationalism |

V. Choosing a nationalism (cont.) (a) Ethnic (b) Liberal (c) Economic (d) Republican (e) Civic (f) Reactive VI. Comparing Types of Nationalism |

V

Choosing a Nationalism

(continued from part 1)

Here we shall examine six types of nationalism popular in Australian history – ethnic, liberal, economic, republican, civic and reactive. In the following discussion I argue that an identitarian variant of the liberal type is the most balanced, capturing elements of the other positive types while retaining the authenticity and prudence of the Anglo Saxon political tradition.

(a)

Ethnic nationalism

Ethnic nationalism treats the nation as an extended family. More than other nationalisms it most directly identifies and protects ethnic interests because it seeks to establish a relatively homogeneous, cohesive and independent society. Common types are nation states and semi-autonomous cantons in a Swiss-style federation. Motivations are directly tribal, including ethnic nepotism, the wish to defend, tend and live among one’s own people.

These motives have evolutionary origins in kinship. Cultural similarity mimics kinship, especially shared religion and historical memories and belief in descent from common ancestors. In racially diverse regions, ethnic genetic kinship is typically equivalent to that between first cousins. This makes the ethnic group a large store of each member’s distinctive genes.1 Ethnic kinship facilitates the spread and maintenance of ethnic nepotism, a weak but pervasive social tie.

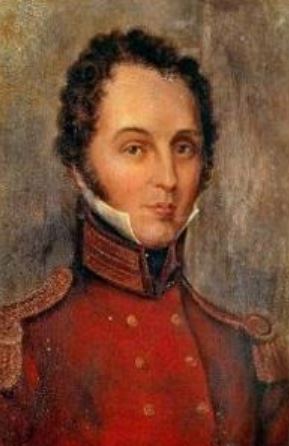

Sir Richard Bourke

Ethnic sentiment was hinted at and stated outright in early decisions to ban non-European immigration to Australia. Arthur Phillip, the first governor of the Sydney colony, refused the British Home Secretary’s proposal to obtain wives for the convicts by taking women from South Pacific islands. Instead he requested more female convicts be sent from England. Other early governors such as Sir Richard Bourke and Sir George Gipps took a similar stand against the importation of cheap Indian labour. This time the proposal came from squatters facing labour shortages. The Colonial Office concurred with the governors, citing the adverse effect on the wages of white labourers of introducing migrants of “an inferior and servile description”. Notice the concern with the working conditions of people of European descent in particular, not citizens in general. The first is an ethnic category, the second a civic.

Anglo ethnicity was an explicit part of Australia’s national identity during the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth centuries. The reaction to mass Chinese immigration in the 1850s had an ethnic dimension, which was in the minds of those who drafted federation in the 1890s. The first legislation passed by the federal parliament in 1901 was the Immigration Restriction Act, which effectively barred non-Europeans. Australia’s armies in the two world wars were conscious of Australia’s identity, its continuity from the First Fleet, and their duty to fight for King, Empire, and a British Australia. These grand displays of solidarity derived in part from ethnic nationalist sentiment. Australia’s core European identity is the result of restrictive immigration policies consciously chosen by generations of Australians.

Sir George Gipps

Traditional patriotism overlaps ethnic nationalism. God, king and country are all implicit ethnic markers, especially in the context of a European society planted in a non-Caucasian region. These symbols elicited popular loyalty in Australia from 1788 until after the Second World War, as they had done in England for centuries. Initially, Australia’s national identity was inherited from England’s, carried by Protestant British settlers. Australia can thus trace its national identity back to Anglo Saxon and Celtic antiquity.

An advantage of ethnic nationalism is the evolved response to national symbols. Humans evolved in homogeneous social groups. We are innately primed to distinguish ethnic kin from strangers. In the words of ethologist William Hamilton:

[S]ome things which are often treated as purely cultural in man […] have deep roots in our animal past and thus are quite likely to rest on direct genetic foundations. To be more specific, it is suggested that the ease and accuracy with which an idea […] strikes the next replica of itself on the template of human memory may depend on the preparation made for it there by selection – selection acting, ultimately, at the level of replicating molecules.2

Hamilton included ethnic sentiments among those for which people are innately predisposed. His ethological concepts might be strategically useful. Political and cultural activists commanding meagre assets would be wise to distinguish between “releaser” and “non-releaser” political ideas. The former unlock pent up innate motivation. The latter rely on conditioning or training. This can be culturally induced but can also involve genes.

Examples include references to the blood of patriots, security of the homeland, portraying the nation as a family (“fatherland”, “motherland”), and so on. As already discussed, “nation” connotes ethnicity and as such is a biological, tribal concept. Such rhetoric has been shown to release patriotic motivation.3 The effect is so pronounced politicians use releaser ideas in order to gain legitimacy. They use terms such as “nation” and “community” and “sovereignty” and “borders” and “homeland defence” incessantly. But the rhetoric is out of kilter with their policies, and the discrepancy is becoming evident to a growingly cynical, distrustful electorate. A competent media or an aroused citizenry would make it difficult for mainstream politicians to use this rhetoric.

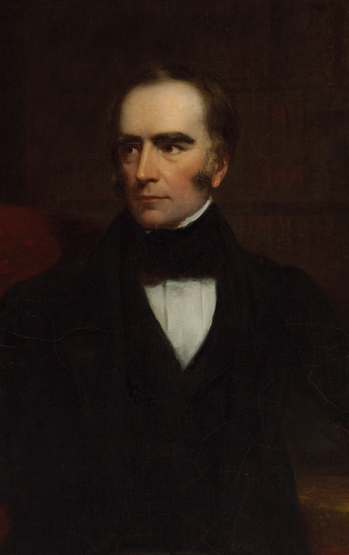

William Hamilton

Because releaser ideas fit naturally with people’s evolved predispositions, they have greater effect with less effort. They are efficient. Ideas that fit less naturally do not release instinctive fixed action patterns but must be inculcated through repetition, which is costly. Unnatural ideas rely more on power, on monopoly of the media and education curricula. Perhaps that explains the globalist left’s intolerance – they do not tolerate any opposition because their ideas are unpalatable.

Releaser ideas confer some resistance to hostile indoctrination. The establishment controls the instruments of mass persuasion in the education system and mass media. But they cannot (yet) change human nature, which has been prompting revolts against the unsettling changes that have been forced on Western societies since the 1960s.

Until the 1960s, Australia benefited from the loyalty of its cultural elite, something inherited from England. Societies with leaders who share the people’s national sentiments are immune to revolution. This was an insight of Italian Communist Antonio Gramsci, who proposed that revolution against Western societies would only succeed if radicals supplanted the traditional bearers of culture. Cultural leaders were present at the start of British settlement in Australia. Reverend Richard Johnson was appointed chaplain of the colony, arriving with his wife in the First Fleet. He blessed the colony in the first Christian service held in Australia, in February 1788. He was succeeded by the Reverend Samuel Marsden. These clergy were loyal to England and its traditions, a loyalty Gramsci argued needed to be broken for communist revolution to succeed.

Also present from the start were scientists such as Joseph Banks, who accompanied James Cook on his voyage of discovery of the south Pacific, 1768 to 1771. With the arrival of free settlers, Australia’s population more closely reflected British civil society. In addition to farmers and artisans there were professionals engaged in law, engineering and science. Australia’s first university was established in Sydney in 1850, the second in Melbourne in 1853.

Antonio Francesco Gramsci.

The late 18th century was a period of transition in English cultural leadership. It was changing from traditional church-based to rationalist university-based. As an English colony, Australia experienced the same transition. The Scottish Enlightenment, which preceded and inspired the English, had produced great philosophers such as Adam Smith and David Hume who influenced the American revolutionaries. Academics would rise in prominence until by the mid twentieth century they had largely replaced Church leaders as cultural authorities. They had a rudimentary understanding of ethnicity and nationality due to the late blossoming of the social sciences in the first half of the twentieth century. These intellectuals were typically patriotic, certainly not hostile to their national or civilisational identities. Many retained elements of traditional patriotism. They were liberal nationalists.

(b)

Liberal Nationalism

The notion of liberal nationalism might seem oxymoronic, especially to Americans, in an age when ‘liberal’ has come to mean leftist or socialist. Here the term’s original meaning is adopted, namely rational approaches to policy that emphasise individual rights and individual conscience.

Liberal philosophers inherited cultural leadership from traditionalists. Philosophers such as Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill were reformers and patriots at the same time. They did not question the continuity of their people or civilisation. They were not afflicted with group guilt. Despite being reformers, by modern standards they were conservative in outlook. They represented continuity with traditional patriotism.

Jeremy Bentham

Conservative patriotism was largely atheoretical, based not on texts and research but on rituals of state and church that stamped participants with identity and loyalty. Its considerable influence was rigid, implicit, part of the nation’s sympathetic nervous system. The evidence-based reasoning that had for centuries informed the legal process had not been extended much to sociological matters, though the potential for such a development was shown by the political theories of Thomas Hobbes in the seventeenth century and Edmund Burke in the eighteenth century. The new liberal nationalism – really an extension of British political tradition – was based partly on early philosophical steps towards sociology. It was explicit and theoretical. It would be influential among Australian leaders for generations, and confirm Australia as an Anglo-European nation.

Parallel developments were happening in the other Anglophone countries such as the United States. Kaufmann’s history of Anglo liberalism in the U.S. from the mid nineteenth century to the mid twentieth finds within it traces of ethno-religious ethnocentrism, sometimes pronounced.4 Anglo liberals of that period could not imagine the United States without a major role for their people. This has also been true of Australia. Here ethnic nationalism, often implicit, helped influence social policy. Just as important was the British political inheritance: rule of law, representative democracy, and institutional pluralism, though these cannot be neatly separated from ethnic tradition because for Anglos they constitute elements of primordial identity. From the earliest years of British settlement, administrators were influenced by ethnic affiliation as well as traditionalist and liberal ideas.

John Stuart Mill

Liberalism fitted into this process partly through the ideas of John Stuart Mill. In a publication of 1861, Considerations on Representative Government, Mill posited a connection between democracy and ethnic homogeneity, more focused on nationality than Burke’s warning against ethno-cultural diversity, that “monstrous medley of all conditions, tongues, and nations”.5 Mill’s theory became popular in literate circles well before the constitutional conventions of the 1890s and remained influential until the 1960s. Mill’s main policy conclusion was that social cohesion necessitates assimilation, and therefore ethnically selective immigration. The greatest of Australian adherents was Sir Henry Parkes, long-serving premier of New South Wales and father of federation.

Mill posited a connection between national identity, homogeneity and democratic values. He concluded:

Where the sentiment of nationality exists in any force, there is a prima facie case for uniting all the members of the nationality under the same government, and a government to themselves apart […] One hardly knows what any division of the human race should be free to do if not to determine with which of the various collective bodies they choose to associate themselves.6

In Considerations Mill argued that representative institutions are “next to impossible in a country made up of different nationalities”. Democracy depends on society being educated and cohesive. As Mill thought that ethnic diversity reduced social cohesion, he concluded that diversity should be minimised. His argument concerned ethnicity, of which race is only one component. “The sympathies available for the purpose are those of race, language, religion, and, above all, of political institutions, as conducing most to a feeling of identity of political interest.”7

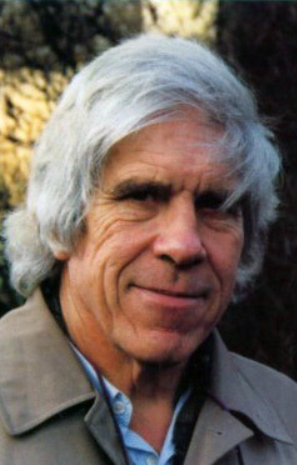

Henry Reynolds

Historian Henry Reynolds has called Mill’s theory “liberal nationalism”, meant as a damning epithet because Mill’s analysis favoured majorities as well as minorities.8 Indeed, many Australian leaders, including Parkes, were convinced by Mill’s argument and used it to create policies that perpetuated and built the modern Anglo nation of which Reynolds disapproves. Were Parkes and other leaders wrong to accept Mill’s theory? Did the theory deserve to have such influence on immigration law?

Historian Phil Griffiths dismisses the view that democracy is facilitated by ethnic homogeneity and maintains that Parkes and other Australian leaders were misled by Mill.9 He implies that a multi-racial Australia would have remained democratic. In fact various lines of analysis support Mill’s theory. Global comparison of societies around the world finds that democracy is relatively unstable in societies with substantial degrees of economic inequality, which ethnic diversity promotes.10 Numerous studies also find that public altruism (“sympathy” in Mill’s writing) and thus social cohesion decline as ethnic diversity rises. Diversity is the second best predictor of civil war after weakness of democracy.11 Mill’s and Parkes’s concern with diversity is vindicated by extensive research, which helps explain the durability of the assimilation paradigm that continued to inform policy making until the early 1970s.

Democracy is an early victim of multiculturalism. Race relations boards and anti-free speech legislation such as the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth.) were established early in Australia’s experiment with unrestricted immigration. Mark Lopez’s award-winning history of multiculturalism shows that multiculturalism and indiscriminate immigration were top-down impositions.12 In breaking down restrictive immigration, activists took pains to avoid allowing citizens to vote on the policy. From the start it was obvious that growing ethnic diversity caused social tensions, as pointed out by Arthur Calwell, ex-Labor leader and the architect of post-WWII immigration.13

Phil Griffiths

Strictly speaking, liberal nationalism need contain no national sentiment at all, only policies for making society cohere within the frame of representative democracy and individual liberty. Policy might be ethnically selective but not necessarily the motives for advancing those policies. The starting point of Mill’s analysis of nationality (immigration, domestic affairs) is not loyalty to a particular tribe but universals of social behaviour, conflict avoidance, and civil liberties, especially freedom of speech and association. These liberal goals imply nationalist policies when viewed through the lens of reason. Liberal nationalists see identity as a means as well as an end. They seek the universal public goods of community and social cohesion and the multiple benefits that result.

Examples of convergence between liberalism and ethnic nationalism are not hard to find. This is David Leyonhjelm, Senator in the Australian Parliament, arguing for naturalness of discrimination by individuals:

[D]iscrimination by individuals is a part of life. We all discriminate, every day. There are no exceptions. Whether it’s based on appearance, behaviour, personal attributes, location, beliefs or whatever, it’s natural and it’s integral to making choices. How much should the government intervene to prevent us from making certain choices? Libertarians view such intervention as primarily the role of civil society, not the government.14

This view, based on the distinction between the private and public spheres, can be applied to assert individual freedom to discriminate on the basis of any identity, something Mill would have approved. Asserting that liberty would curb multiculturalist tyranny over the nation.

Identity issues can also emerge from the liberal distinction between government discrimination exercised internally, which is generally a threat to liberty, and externally, which can be essential to defend liberty. Senator Brian Burston of Pauline Hanson’s One Nation party implied this distinction in calling for selective immigration policy.

It is government’s duty to discriminate at the borders to ensure that newcomers are compatible. External discrimination reduces the need for citizens to discriminate internally, for example in choosing where to live and to which schools to send their children. That preserves domestic peace. That is why One Nation promises to discriminate by cultural and religious identity in selecting migrants and refugees […]15

Senator David Leyonhjelm

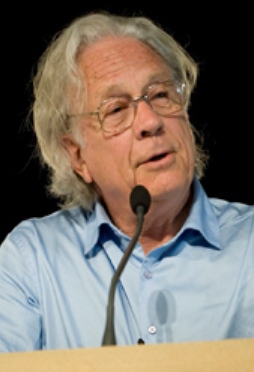

An example is Hans-Hermann Hoppe’s recent enunciation of libertarianism, which overlaps classical liberalism in emphasing the need for freedom from coercion and conflict. Hoppe concludes that immigration to Western societies should mainly consist of people descended from ethnic Europeans – “Western, white candidate immigrants” – not because of any ethnic preference but in the interests of social harmony, neighbourliness, and economic equity.16 He criticised the goal of white solidarity on the ground that many globalist elites are white.17

Genuine liberal nationalism is open to the idea that nationhood is beneficial for all peoples. This is another advantage over unregulated ethnic nationalism, which is prone to chauvinism, resulting in needless conflict. Universal nationalism has the potential to facilitate cooperation among parochialists against global centrists.

Senator Brian Burston

Universalism risks drifting too far from local interests. Stability of liberal nationalism as an ethnic strategy probably depends on more than perceived fairness, privacy and equality before the law. Hoppe’s rejection of ethnic solidarity misses the fact of ethnic kinship. Social divisions do not eliminate the interest we have in the welfare of our peoples. Genetically and civilisationally, class is false consciousness.

For these reasons it is rational for ethnic nationalists to join in discussions of liberal nationalism, clarifying matters of fact and reasoning to yield outcomes more amenable to ethnic interests.

Is the reverse also true? Can it be rational for liberal nationalists to emphasise ethnic identity in some circumstances? That is possible considering liberalism’s enlightenment values. Ethnic kinship is now quantified and shown to be substantial. It is adaptive and natural for people to care about their ethnic and cultural groups. If liberals wish humans to be happy and adaptive, they should support the positive aspects of ethnic nationalism. Certainly a moderate and rational nationalism will acknowledge ethnic sentiment as a matter of free choice and dignity.

(c)

Economic Nationalism

The labour movement from the late nineteenth century advanced the most electorally influential case for ethnically restrictive immigration. Non-European workers were seen as a threat to white wages. This view led to the Labor Party becoming the most powerful advocate of ethnic restriction as the franchise widened. This continued until the Party abandoned the Anglo working class starting in the 1970s, under the new leadership of European-style social democrats.

Economic nationalism parallels liberal nationalism, though it is not a subset of it. Both generate nationalist policies from non-ethnic motives. Because the wish for dignified wages was seen as a prerequisite for social cohesion, labour and liberal policy on immigration overlapped. When liberals accused pastoralists seeking to import cheap Islander labour of “Toryism and oppression” they were also defending the future labour movement.18 Already quoted is the Colonial Office of 1842 banning the immigration of Indian labourers because it was believed they would become a permanent lower class, dividing society. This was in line with the liberal view of J. S. Mill that in the interests of maintaining free institutions, boundaries of government should correspond to boundaries of nationality.

Hans-Hermann Hoppe

Like liberalism, the labour movement’s motives were not wholly unrelated to identity. The explicit motivation was economic – protection of wages and working conditions – but there was always an identitarian motive, usually implicit but often out in the open. The founders of the Labour movement were primarily concerned with protecting workers of the Australian nation, not workers of the world.

The prospect of a permanent non-white lower class was ameliorated somewhat in Australia by selection of immigrants for economic ability. Nevertheless, Australia has not bucked the trend detected overseas, of racial inequality and stagnant wages in various sectors caused in part by large scale immigration to those sectors. Identitarian fears have been realised with the wholesale alienation of many suburbs in large cities. The poor outcomes shown by refugees, unselected for economic compatibility, confirms the most dire economic prediction.

The other economic concern, based on Gold Rush experience, related to competitive non-European immigrants. This concern has been vindicated. Since the late twentieth century, Chinese and some Indian immigrants have displaced large numbers of native-born Australians from the best state-run schools and universities. They are on course to be overrepresented in the managerial and professional class, as documented by the late Peter Wilkinson in The Howard Legacy.19

There is also economic anti-nationalism, a globalist idea in big business. The corporate interest in maximising profits can generate policies that erase borders as a means of freeing up the movement of labour. Economic nationalism on the part of workers has been a recurring complaint coming from globalist ideologues.

(d)

Republican Nationalism

This was a doctrine more acceptable to the radical left than either ethnic or true liberal types. Many on the left were of Catholic Irish extraction, for whom republicanism had the attraction of attacking symbols of the English nation that had dominated Ireland for centuries. The crown and the union flag would be removed if a republic were instituted. This leftist-Irish republicanism was thus a front of the long-standing conflict between Irish Catholics and Protestant English, first manifested in Australia in the Vinegar Hill rebellion of 1804, just 16 years on from the First Fleet. It should be emphasised that many people of Irish Catholic extraction did not oppose the emerging Anglo-Australian nation. During the First World War 6,600 immigrants born in Ireland volunteered for the Australian armed forces.20 Another example was the Labor leader Arthur Calwell, who was both an active member of Melbourne’s Irish Catholic community and a staunch advocate of the White Australia Policy.

PM Arthur Calwell

Republican nationalism seeks to divorce national identity from Anglo markers of race, culture and history, though in principle it is compatible with broader ethnic and religious identity. An early advocate was Keith Murdoch and his son Rupert. Anti-English sentiment found an ally in Irish-Catholic sentiment, manifested in the anti-conscription campaigns during the First World War. A leader of the anti-conscription cause was Irish immigrant Archbishop Daniel Mannix. By the 1960s Irish identity was channelled through republicanism, as a way of attacking the symbol of historical oppression, the British crown. The monarch is not only Australia’s head of state but an ancient ethnic marker of Anglo identity. Republicanism rose to prominence during the Whitlam government, 1972 to 1975. It was the precursor of civic nationalism, which extended republican abstractions to allow immigrants from anywhere. The ever deepening political corruption of the social sciences facilitated the slide from republicanism to multiculturalism, by giving legitimacy to claims for minority privilege.

In principle an Australian republic could retain Anglo-Christian identity. As minorities have assimilated, many have identified with the mainstream. Unfortunately, rapid demographic change has brought a large minority voting base behind the republican cause. Republican nationalism is now largely disconnected from the interests of Anglo Australia.

One common misstep of republicans is to confuse the nation with the federal state, which in Australia is known as the Commonwealth. Politicians and commentators assert that the nation came into existence at federation in 1901, when in fact national consciousness had arisen earlier and was an important motivation of the federal movement. This error became a mainstay of civic nationalism.

(e)

Civic Nationalism

Civic nationalism has little if anything to do with the nation. Instead of shared memories developed over centuries and ethnic kinship evolved over millennia, proponents assert that shared values suffice to create social bonds. Scientific support for civic theory is fleeting. Instead it is based on intellectual fashion and censorship (“political correctness”).

Civic nationalism is the idea that social cohesion and loyalty can be engendered by identification not with the country’s founding ethnicity or culture but with ideals such as the rule of law, the constitution or tolerance of deviant sexualities. Government doctrine now completely confounds commonwealth, a political structure, and nation, a population united by a sense of shared ancestry. Politicians from both sides of politics insist that the legalism of citizenship is sufficient to secure loyalty.21 This absurdity is used as justification for permanent mass immigration, when the real movers are powerful lobbies.

Tanya Plibersek

An excellent example of civic nationalism was provided by Labor’s Tanya Plibersek, Deputy Opposition Leader. Even more than the Coalition government, Plibersek equates patriotism with citizenship. “[C]itizenship is what holds our proudly multicultural nation together.” In her view, citizenship has little to do with objective commonalities such as speaking the same language. Instead it is underpinned by progressive values such as mateship, solidarity (sharing), and loyalty to Australia. Plibersek does not explain how a legal status could engender such motivations, apart from students being made to repeat the oath of citizenship in schools.22

Globalists and minority activists like civic nationalism and its faith in citizenship because it allows for open-ended mass migration and the votes it brings. Anyone, they maintain, can become Australian (or any nationality) simply by swearing loyalty to a list of values. There is, they claim, no need to identify with the country’s Anglo-Celtic population and its history or adopt Christianity because neither has a special claim to national identity. The pledge of Commitment as a Citizen of the Commonwealth of Australia is specified in Schedule 1 of the Citizenship Act 2007 (Cth.).

From this time forward,

I pledge my loyalty to Australia and its people,

whose democratic beliefs I share,

whose rights and liberties I respect, and

whose laws I will uphold and obey.23

This barely hints at Australia’s national identity, the glue that binds our far-flung population.

The Immigration Minister, Peter Dutton, does not rebel at this legislation, which was passed in 2007 by the Coalition government of John Howard. Dutton’s greeting to new citizens, read at a citizenship ceremony in Wyong Council chambers on 28 August 2017, did not mention the nation, its origins, its pioneers or founding culture and religion.24

The history and culture of Australia has been forged over thousands of years, first through Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and more recently with people from the four corners of the earth.

This is not true. It omits the British people who explored, pioneered and named Australia, building it into a thriving nation by the late nineteenth century. Dutton was not finished.

People of all backgrounds and religions strengthen our country and only together, united will our future be as strong as our present and past.

Neither the citizenship ceremony nor the speech of the immigration minister instructed immigrants who and what Australia is, from where it came, or who made it. The electorate is not offered an alternative to this treason. Tanya Plibersek calls Dutton a member of the “hard right” faction of the government.

Peter Dutton

This is civic nationalism. Its proponents reject the idea that ethno-cultural identity, especially that of peoples derived from Europe, is indispensable for securing cohesion and loyalty.

The Liberal and Labor parties switched from ethnic to civic nationalism in the 1960s, and by the 1970s were adopting one variant, multiculturalism. Because they discounted organic cohesion they were driven to rely completely on citizenship as the primary social glue. The nation is routinely equated with the Commonwealth, ignoring over a century of Anglo nation building. United Nations policies and associated rhetoric are given free rein. These innovations were adopted without scientific or historical evidence that social cohesion is viable in diverse societies. The evidence is still absent. Nevertheless, it was not difficult to find radical sociologists willing to assert that ideals or values or the constitution could substitute for primordial identity. Scholarship and science dedicated to understanding ethnicity was all but absent from the universities, a situation not much improved in the early 21st century.25

One problem with basing cohesion on values is that the process of political compromise inevitably reduces values to shallow slogans. As the conservative educationalist Kevin Donnelly explained, “even when there is agreement on what constitutes Australian or Western values, […] the list is so vacuous and all-embracing that it’s impossible to identify what makes such values special or unique”.26 Australians are meant to be united by such values as tolerance and inclusion and respecting different points of view. Particular religious and ethnic origins are not even named on the assumption that all cultures are equal.

Kevin Donnelly

The tenets of civic nationalism are not altogether new. Empires have universalised the head of state and expanded citizenship to win the loyalty of far-flung provinces. This was an innovation of the Romans, emulated by the British. In neither case did the patrician class believe that provincials were their equals but in both cases they used citizenship to gain loyalty based on equal treatment under the law. Equality included the legal right to migrate around the empire. Omnivorous citizenship in the Roman and British empires resulted in the mass migrations towards the metropolitan society.

Cynicism and shortsightedness are apparent in these imperial ideologies. Of relevance to Australia is the use of the equality doctrine by Joseph Chamberlain, Colonial Secretary in Whitehall, to block the colonies and the new Commonwealth from explicitly selecting ethnically European immigrants. The experience of Chinese immigration during the gold rushes showed that a European country situated beside the large populations of Asia could only retain its identity by systematically favouring European immigrants. But the British government wished to sign a naval agreement with Japan, for which purpose they needed to secure Japan’s favour. Chamberlain wrote to warn Australian leaders that the British government would advise the monarch to refuse the royal assent to any explicitly racial provision. His words, read by Deakin during the debate on the restriction bill, sound like those of a globalist:

Any attempt to impose disqualifications on the base of [place of origin, race or colour] is contrary to the general conceptions of equality which have been the guiding principle of British rule throughout the Empire.27

As we have seen, equality can be a doctrine of Empires. More often they rely on violent conquest and the putting down of uprisings, both involving the exercise of radical inequality. Chamberlain knew that. Proof of his pragmatism came a few years later when he offered the Zionist movement 15,000 square kilometers of prime land in Kenya, a British possession. He also favoured granting them land in the vicinity of Palestine and elsewhere in the Empire. He did not seek the permission of the Kenyans or the Palestinians, which one would expect from a man imbued with conceptions of equality.28

In fact civic nationalism is often a thin cover for ruthless expediency and cosmopolitanism. Its empirical claims are either exaggerated or confected. People can be indoctrinated to follow a flag or a slogan. But it takes more than arbitrary symbols to unite communities.

(f)

Reactive Nationalism

The reactive type has been influential. It will be briefly discussed, though it is not animated by a consistent ideology. Instead it is a manifestation of anxiety with rapid change and resulting frustration with and suspicion of the authorities.

Joseph Chamberlain

Reactive nationalism carries bits and pieces of ideologies and policies propelled by emotion. Common denominators of national identity remain largely implicit and unanalyzed.

These are negative features because emotionally-driven politics tends to be inchoate, leaderless, episodic as it reacts to overreach by elites, including oppressive social controls.

Nevertheless, any effective mass political movement will be impelled by reactive sentiment. Hans-Hermann Hoppe’s analysis is again relevant. He states that any realistic libertarian strategy for change must be a populist strategy. That is, they “must short-circuit the dominant intellectual elites and address the masses directly to arouse their indignation and contempt for the ruling elites”.29

The Trump and Brexit revolts were based on passionate rejection of globalist social transformation and stifling social controls. The same reactions have propelled Pauline Hanson’s electoral success.

True liberal nationalism would respect the energy and passion of reaction, while channeling it into traditional democratic politics. To be acceptable to identitarians, the larger movement must include individuals who are intensely motivated, whether by reaction or religion or ethnic nepotism, because they, not dry intellectuals, can defend the nation against opponents empowered by their own reactionaries, zealots and ethnic activists. Reactionaries and liberals differ in arguments and motivation but they make a formidable combination when facing a common foe.

VI

Comparing Types of Nationalism

The six types of Australian nationalism have been combined in various ways over two centuries, concluding in the 1970s with a relatively disjunctive break with the ethnic-liberal combination that had shaped the nation from the First Fleet.

All types of nationalism have encompassed bad decisions and unrealistic assumptions. But overall, ethnic and liberal nationalisms have proven less susceptible to elite free riding. The liberal type has the added advantage of retaining political forms developed over centuries that help the formation of public goods.

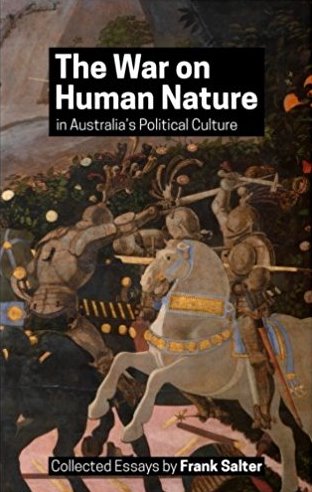

Frank Salter, “The War on Human Nature in Australia’s Political Culture: Collected Essays” (Social Technologies, 2017)

Australia’s current mix of civic nationalism and multiculturalism constitutes a top-down elite agenda. It co-exists in antagonistic tension with latent ethnic nationalism, as demonstrated by the recent success of minor parties. The antagonism is caused by the multicultural establishment seeking to transform the original nation. Their dominance of the culture industries has not eliminated popular nationalism, which remains a sleeping giant.

All types can be used to mask agendas other than social cohesion and identity. But true liberal nationalism should be relatively self-correcting because it values free speech and rationality.

Liberal nationalism has the advantage of self-criticism. We all operate with imperfect knowledge. By opening our beliefs to rational inspection we increase the chance of avoiding ill-informed ingrained assumptions, including those concerning goals and methods. A moderate culture of self-criticism allows a movement to adapt to changing conditions, including new tactics and strategy by opponents and potential allies. This nimbleness will be indispensible in defeating more powerful opponents.

In principle, liberal nationalism encompasses any lawful approach that builds sustainable social cohesion, except authoritarian government, coercion and deception. It contrasts with Australia’s version of civic nationalism, which relies on all three methods. These characteristics indicate vulnerabilities. Civic nationalism and the undemocratic multiculturalism it deploys can be subverted by ethnic and liberal nationalist memes. Methods should include exposing the lies and irrationality and coercion inherent to these ideologies. The internet is invaluable because it is difficult to suppress. Insurgents should also concentrate their resources on educating the public about identity, the connection between identity and social cohesion, and the likely outcomes of present policy. The hostile forces behind civic nationalism and multiculturalism should be exposed.

Irenäus Eibl-Eibesfeldt and Frank Salter (eds.) “Ethnic Conflict and Indoctrination : Altruism and Identity in Evolutionary Perspective” (Herndon: Berghahn, 2001)

Contemporary liberal nationalism – the civic kind hegemonic on both sides of politics – is a lie, a cover for the subordination and displacement of white majorities. Politicians who profess it are often not nationalists at all, regardless of their rhetoric. They do not care about national identity. There is always the risk that genuine forms of liberal nationalism might again collapse into the civic kind as it did under the Coalition from the 1960s, with sound analysis replaced by ideology and the people’s voice shouted down by media in thrall to special interests.

Patriots should encourage and support majority ethnocentrism among activists and politicians. They should support organisations that lobby for the historic nation in multicultural politics. A powerful Anglo council would help proof liberal nationalism against the slide that occurred in the 1960s. It would provide career paths for promising activists, and provide opportunities for the public to support patriotic causes. A liberal nationalism that sought to advance evidence-based policies to promote social peace would go a long way to protecting national interests because the strongest social bonds are parochial. That is why ethnic nationalism is often compatible with liberalism regarding the costs of diversity and the benefits of protecting the core identity.

Liberal nationalism’s main weakness compared to ethnic nationalism is its tendency to collapse into the civic kind. The weakness lies in its reliance on ideas transmitted by higher education, at a time when universities have been captured by the West-hating left. Ethnic nationalism is less vulnerable in this respect because it has a stronger emotional basis in ethnic nepotism. It would remain loyal to the nation even if diversity were found not to have multiple negative impacts, because ethnic nationalists are willing to pay a price to live among their people in a relatively homogeneous self-governing society. The weakness of this doctrine is cultural, leading to rigidity of policy and ideas. The end result is compromise of the representative democratic system.

Ethnic nationalism, and certainly the reactive type, are insufficient credentials for an individual or party to assume government, unless ethnic identity is taken to include the political traditions inherited from England. One way or another, nationalist voters are advised to elect only those politicians who have demonstrated competence, character and tradition in the broad sweep of government duties in the tradition of representative democracy. One marked weakness of unqualified ethnic politics is that it risks emulating multiculturalism’s effect of fragmenting society along ethnic and religious lines. This has a direct human cost in social conflict and an indirect economic cost due to policy being diverted from serving public goods to serving particular group interests. Multi-national states such as Belgium and Switzerland show how liberal government softens the negative effects of identity politics by guaranteeing individual rights, including the right to elect representatives to parliament.

Given its mixed history, liberal nationalism might appear to be unreliable. One sign that it could be reclaimed is that every instance of it serving hostile goals has entailed fraud, the compromise of Enlightenment values of rationality and liberty. That is the case with so-called liberal internationalism, the ideology of globalist elites since the Second World War. To give just one example of that compromise, ex-High Court judge Dyson Heydon notes that Christianity is routinely attacked in the elite media and education system, two sectors dominated by liberal internationalism. Political repression is being turned against the expression of Christian values, such as heterosexual marriage. Heydon points out that elements of Australia’s cultural elite insist that no religion, especially Christianity, should be safe harbour for dissent from liberal globalism. He doubts that these elites are worthy of the name “liberal”.30 He is correct. True liberalism based in science and protection of freedoms does not attack religion, dissolve borders or displace nations.

Australia’s historical experience – of liberal nationalism giving way to globalism – indicates that liberal nationalism is sustainable only when it respects majority ethnic and religious identity as legitimate values. Liberal nationalism’s divorce from ethnic identity in the decades before 1970 opened it to intellectual corruption and left-authoritarianism. The same is true on the other side of politics. Multiculturalism would be less effective if it had no minority leaders but relied upon cosmopolitans versed in abstruse theory. It is more effective for the purpose of combating the majority to have leaders whose cosmopolitanism is a tactic serving minority ethnic loyalty.

When ethnic motivation, any motivation, exercises political power it is prudent to have that power constrained by liberalism – rule of law, division of powers, evidence-based policy, and protection of civil liberties. In the case of multiculturalism, its radical allies act in the opposite direction, subverting traditional constraints on government.

Frank Salter, “Welfare, Ethnicity and Altruism : New Data and Evolutionary Theory” (London: Frank Kass, 2004)

Ethnic and liberal nationalism have different strengths in relation to multiculturalism. The growth of an ethnic nationalist movement would be accelerated by the strategy of democratic multiculturalism described earlier, due to rising Anglo consciousness. However, the doctrine does not provide a political framework for accommodating other identities when the state is retaken. At that point a liberal frame would make an emerging ethnic state more governable, more stable, by providing political processes for managing diversity.

Ethnic activists fit into the liberal nationalist fold as individuals who recognise group fitness as a utility to be protected. Ethnic nationalism has the advantage of directly providing for the welfare of ethnic kin. Because members of an ethnic group share a substantial proportion of their genes, ethnic welfare constitutes a reproductive interest, in the same way that children do. Evidence is accumulating that ethnic homogeneity, a typical nationalist policy, reduces intra-group conflict and increases altruism. When combined with protections of civil rights, nationalism is a public good.

The classical liberalism of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill was based on utilitarianism, an ethical theory based on maximizing individual happiness. They never included ethnic welfare as a formal utility. They probably had national feelings, but left them implicit and formally unconnected to their political philosophy. Liberals who believe that ethics should advance fitness might be called “adaptive utilitarians”.31 Like happiness, the goal of fitness entails a robust degree of national autonomy.

Informed liberal nationalism can be an effective, though partial, defence of majority ethnicity against globalists and multiculturalists. That is because it converges on ethnic nationalism at the policy level. Historically, liberal nationalism respected ethnic sentiment. Together the liberal and ethnic types encompassed motives rational and civic on the one hand, and nepotistic on the other. Together they promoted the national bio-culture.

Frank Salter, “Emotions in Command: Biology, Bureaucracy, and Cultural Evolution” (Somerset: Transaction, 2008)

The fusion of liberal and ethnic nationalism that shaped Australia for two centuries is better equipped with releaser memes than competing doctrines. On the liberal side, that is because institutions such as representative democracy and rule of law are part of Anglo identity, and therefore add another cultural layer to markers of descent.

Demanding truth in and from government will do much damage to the credibility of global liberalism and indirectly raise the ethnic consciousness of Anglo Australians. Enlightenment values are on the side of universal nationalism.

The main disadvantage of this approach is when its identitarianism is implicit. Only an explicit appeal to the historic nation can establish a nationalist rhetoric able to fully mobilise Anglo Australians.

Implicit ethnicity also has advantages. Decades of indoctrination by media and education bureaucracies have made Anglo ethnic nepotism taboo. Liberal nationalism advances ethnic interests indirectly. Indirect ethnic preservation has the additional attraction of conforming more with the non-ideological tradition of Anglophone cultures. English-derived politics is famously divorced from theory compared to the Continental tradition. People distrust theory in politics, as much as they do theory in art. They perceive both as pretentious. Like conceptual art, a political position won’t appeal to the common-sense public if it relies on abstruse theory. But everyone understands and desires social peace, stability and prosperity, which true liberal nationalism would protect better than bogus civic nationalism.

To put this another way, the choice of types of nationalism is not only an intellectual exercise. It is also one of self-examination. The choice must feel right to the majority now or in the foreseeable future. And that depends on who we are psychologically, who we are in terms of shared memories, and who we could feasibly become as new memories slowly accumulate and the culture changes. Multicultural critics portray Anglo-Australians as uniquely driven by racial identity. In fact Anglo Australians are among the least collectivist of peoples, much less so than multicultural activists. They are so tolerant of foreigners to have retained their composure while being inundated by immigrants.

In reality ethnic activism by and for the majority is awkward in the present political climate. That does not make it inappropriate. In a healthy political culture, one not distorted by a hostile culture industry, positive majority ethnocentrism would seem natural. And it is important that it be so again, because individuals with heightened ethnocentrism are their peoples’ natural guardians, the passionate counterpoint to cold utilitarianism. Like a mother alert to her baby’s cry, ethnocentric individuals of all backgrounds are the first to feel estranged and besieged by social trends that are adverse for their people. Experimental evidence indicates that both forms of care – for infants and ethnic groups – are biologically evolved.32 Both nurture genetic kin.33 Protectiveness towards family and ethnic kin is part of a high-investment life-history strategy. It represents our evolved human spirit. The promiscuous altruism urged on Western societies by its elites is maladaptive, a sure path to social collapse.

Somehow ethnic loyalists’ feelings of group empathy have been preserved despite the desensitising influence of anti-white messages in the media and schools. It is easier for minorities because multicultural ideology praises their ethnocentrism. Indeed, multiculturalists laud minority ethnocentrists. They portray indigenous leaders as resistance fighters and minority activists as champions of civil rights. But ethnocentric Anglos are condemned as racists. That is unprincipled and imprudent because ethnic nepotists are canaries down the diversity mineshaft. Their cries of anguish and anger are early warnings that their people are in danger. Yet they are silenced, often by minority activists whose ethnocentrism is more intense than theirs.

Liberalism’s rationality and moderation, its great strengths, have also been weaknesses. They have exposed the nation to attack by powerfully motivated elites. By the 1970s the civilised ethnic policies that produced White Australia could not be sustained in the face of pressure from minority ethnics and business interests driven by tribal passion and greed. That is why majority ethnic nationalism must be accommodated, indeed treasured, by those who would preserve a harmonious national community. No national settlement is worthy of the name unless it has the vitality to withstand countervailing forces. The intense motivation of minority ethnics and corporate barons can only be countered by equally intense motivation in the service of the majority. Without that balance the proper ethnic hierarchy of plural democracies can be upset. The nation and especially its core identity should have an honoured place. Its constitutional protections should surpass those of all other identities. In Australia, the United States, and other societies subdued by multiculturalism, the founding nations have been subordinated by left-minority alliances. Perhaps only a similar alliance, between true liberals and ethnic nationalists, can re-establish and stabilise the legitimate national order.

Majority ethnocentrists’ expression of concern for their people makes them prime targets of the “human rights” apparatus, part-and-parcel of big-state globalism. Those who chant “all love is equal” excoriate anyone who loves the wrong race. Beginning with the Bolshevik coup in Russia in 1917, a powerful strand of left ideology has sought to suppress human nature to create a communist utopia. The civilised response is the liberal one: society should respect ethnic activists of all stripes, including the red white and blue of the founding people. Attacks on ethnic nepotism are unacceptable in a liberal society.

In particular liberal nationalists worthy of the name should accept individuals who profess the interests of the nation. They should accept as comrades those who do so in liberal terms, something civic nationalists and minority chauvinists can never allow. In practical terms that does not mean allowing national activists to make policy in general, because they represent one interest among many. But it does mean protecting the right to free speech and party membership of those who stand up for the historic nation. Liberal nationalists should do that not only as an expression of civil liberties but as a means of ensuring the multiple public goods that flow from a secure national identity and sovereignty.

This paper has argued that Anglo patriots should use a dual political-cultural strategy to defend the historic Australian nation and reestablish the liberal nationalist state built by the founders. The recent success of nationalist protest parties in many Western societies, including Australia, indicates that voters are ready to confer significant political and cultural niches on leaders who are willing to challenge the dominant culture. There are ways forward.

Dr. Frank Salter

— Dr. Salter received his PhD in Australia (Griffith University) but spent most of his career at the Max Planck Institute for Behavioural Physiology in Germany. Frank has taught in Britain, the US, Central and Eastern Europe. He has authored and co-authored various peer reviewed articles and essays. His most recent book is The War on Human Nature in Australia’s Political Culture: Collected Essays (Social Technologies, 2017). Now returned to his native Australia, he consults on policy and management issues. Dr. Salter’s last contribution to the Sydney Traditionalist Forum was to its 2015 Symposium (“Quo Vadis Conservatism? Do Traditionalists Have a Place in the Current Party Political System?”) titled “Australian Conservatism After Abbott: The Need for Social Movements.”

Endnotes:

- Frank K. Salter, On Genetic Interests. Family, Ethnicity, and Humanity in an Age of Mass Migration (New York, Transaction, 2007 [2003]) Chapter 7.

- William D. Hamilton, “Innate social aptitudes of man: An approach from evolutionary genetics”, Narrow Roads of Gene Land. Vol. 1: Evolution of Social Behaviour (Oxford: W. H. Freeman, 1996 [1975]) at p. 330.

- Garry R. Johnson, “In the Name of the Fatherland: An Analysis of Kin Terms Usage in Patriotic Speech and Literature” International Political Science Review, Vol. 8 No. 2 (April 1987) pp. 165-174.

- Eric P. Kaufmann, The Rise and Fall of Anglo-America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004).

- Edmund Burke, “Reflections on the Revolution in France” (1790) abridged in Essays by Edmund Burke (Melbourne: E. W. Cole, [date unknown]) at p. 37.

- John Stuart Mill, Three Essays by John Stuart Mill (London: Oxford University Press, 1960) at p. 381.

- John Stuart Mill, Considerations on Representative Government (South Bend, Ind.: Gateway Editions, 1972 [1861]) at p. 298.

- Henry Reynolds, “Racism and other national discourses” in Geoffrey G. Gray and Christine Winter (eds.) The Resurgence of Racism: Howard, Hanson and the Race Debate (Clayton, Victoria: Monash Publications in History, 1997) at p. 36-37 cited in Phil Griffiths, “Towards White Australia: the Shadow of Mill and the Spectre of Slavery in the 1880s Debates on Chinese Immigration” Paper presented to the 11th Biennial National Conference of the Australian Historical Association (Brisbane, 4 July 2002) at p 10.

- Phil Griffiths, ibid.

- Tatu Vanhanen, The Limits of Democratization: Climate, Intelligence, and Resource Distribution (Augusta, Georgia: Washington Summit Publishers, 2009).

- Frank K. Salter, “Ethnic Nepotism as Heuristic: Risky Transactions and Public Altruism” in Louise Barrett and Robin Dunbar (eds.) Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology (Oxford, Oxford University Press: 2007) at p. 541-551.

- Mark Lopez, The Origins of Multiculturalism in Australian Politics 1945-1975 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2000) at p. 337.

- A. A. Calwell, Be Just and Fear Not (Adelaide: Rigby, 1978) at p. 118.

- Commonwealth of Australia, Parliamentary Debates, Senate, 27 November 2017, Senator David Leyonhjelm, Marriage Amendment (Definition and Religious Freedoms) Bill 2017.

- Commonwealth of Australia, Parliamentary Debates, Senate, 11 October 2017, Senator Brian Burston, Maiden Speech.

- Hans-Hermann Hoppe, “Libertarianism and the ‘Alt-Right’”, Address to the Property and Freedom Society 12th Annual Conference (Bodrum, Turkey, 14-19 Sept 2017) at c. 45 minutes.

- Ibid. at c. 42 minutes.

- Keith Windschuttle, The White Australia Policy (Sydney: Macleay Press, 2004) at p. 18.

- Peter Wilkinson, The Howard legacy: Displacement of Traditional Australia from the Professional and Managerial Classes (Essendon, Australia: Independent Australian Publishers, 2007).

- Jeff Kildea, “Irish ANZACs: The contribution of the Australian Irish to the Anzac tradition”, Address at the Parliament House of New South Wales on the Commemoration of ANZAC Day (Sydney, 1 May 2013).

- Frank K. Salter, “Towards a Ministry of Emigration – Australian Citizenship and Domestic Terrorism” Submission to the government inquiry into Citizenship Policy, conducted by the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (Canberra, 2015).

- Troy Bramston, “Patriots practice ‘inclusive citizenship’: Plibersek” The Australian (22 Nov 2017) at p. 4.

- Australian Citizenship Act 2007 (Cth) Schedule 1.

- Peter Dutton, Letter by the Minister for Immigration read at the Citizenship Ceremony, Wyong Council Chamber (28 August 2017). The writer was present at the reading.

- Frank K. Salter, The War Against Human Nature in Australia’s Political Culture: Collected Essays (Sydney: Social Technologies, 2016 [2014]).

- Kevin Donnelly, “How can we teach what few really understand?” The Australian (11 October 2017) at p. 7.

- Deakin quoted by Keith Windschuttle, op. cit. p. 289.

- See entry for “Chamberlain, Joseph” in Spencer C. Tucker (ed.) The Encyclopaedia of the Arab-Israeli Conflict: A Political, Social, and Military History Vol. 1 (2008) at pp. 258-9.

- Hans-Herman Hoppe, op. cit. at c. 41:20 minutes.

- Dyson Heydon, “Faith’s Implacable Enemies: Attacks on Christianity Strike at the Protections Enjoyed by Today’s Society” The Weekend Australian (online) (4-5 November 2017) (accessed 5 December 2017) at p. 20.

- Frank K. Salter, On Genetic Interests, op. cit. at pp. 290-298, 319-320.

- Mothering in women and tribal defence by men are primed by the same hormone, oxytocin. In men the hormone produces motivation to tend-and-defend. See further C. K. De Dreu, L. L. Greer, M. J. Handgraaf, S. Shalvi, G. A. van Kleef, M. Baas, F. S. Ten Velden, E. van Dijk, S. W. Feith, “The neuropeptide oxytocin regulates parochial altruism in intergroup conflict among humans” Science No. 328(5984) (June 2010) at pp. 1408-1411. [DOI: 10.1126/science.1189047].

- Frank K. Salter, On Genetic Interests op. cit.

Citation Style:

This article is to be cited according to the following convention:

Frank Salter, “Strategic Considerations for Anglo-Australian Identitarians – Part II” SydneyTrads – Weblog of the Sydney Traditionalist Forum (24 December 2017) <sydneytrads.com/2017/12/24/symposium-ii-frank-salter-pt-ii> (accessed [date]).

Leave a comment