As to the previous essay on Existentialism, it could be surmised that man’s obligation to construct meaning in his own life is limited only to physical, concrete realities. Jung calls these traits an individual’s “character”—the bodily and mental features that are entirely fixed.

As to the previous essay on Existentialism, it could be surmised that man’s obligation to construct meaning in his own life is limited only to physical, concrete realities. Jung calls these traits an individual’s “character”—the bodily and mental features that are entirely fixed.

Insofar as psychology is the science of the human mind, it can be said that the psychologist attempts to understand human nature in general, and the patient’s own character specifically, as it applies to the mind. The physician attempts to understand how a healthy body works and brings the unwell up to that standard. So, too, in a way, does the psychologist attempt to understand how a healthy mind works and bring the unwell mind up to that standard.

But this is only the beginning. There are, Jung asserts, much broader uses for psychology than simply curing the “mentally ill”. In his own words,

To be “normal” is a splendid idea for the unsuccessful, for all those who have not yet found an adaptation. But for people who have far more ability than the average, for whom it was never hard to gain success and to accomplish their share of the world’s work—for them restriction to normalcy signifies the bed of Procrustes, unbearable boredom, infernal sterility and hopelessness.1

This is what this essay will address: not deep-seated mental illnesses such as lycanthropy and schizophrenia, but those who suffer from what Jung calls the “general neurosis of our time”: the “senseless and emptiness” of life.2 The conservative has his pulse on many of these symptoms and potential cures, and could only gain a better understanding of his own struggle—and himself—by exploring the scientific element of these dis-eases.

This is what this essay will address: not deep-seated mental illnesses such as lycanthropy and schizophrenia, but those who suffer from what Jung calls the “general neurosis of our time”: the “senseless and emptiness” of life.2 The conservative has his pulse on many of these symptoms and potential cures, and could only gain a better understanding of his own struggle—and himself—by exploring the scientific element of these dis-eases.

As one last custodial note, it would be wrong for me to say, “Jung says (x); Conservatives agree with (x); therefore, Jung is a Conservative, and Conservatives are Jungian.” There are two problems with this line of thought.

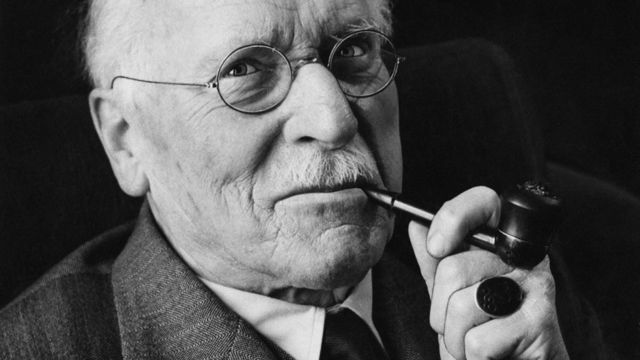

First, Jung was not an ideologist. He was a scientist. He was reluctant to even formulate theories of psychology, let alone theories of political philosophy. There are those who say that Jung was influenced by Nietzsche and Heidegger and other philosophers of an anti-modernist bent. Whether this is true or not, we must remember that Jung was the foremost Freudian before empirical evidence led him to conclude that there were factors at work in the human mind that could not be explained by physical appetites.

Secondly, there are conclusions that Jung arrives at which will not sit well with the most conventional conservatives. Jung is not the Burke of the Psyche; he won’t give the right-winger little quotes or great tomes of information to use against the general Left. His ideas and findings must be judiciously weighed and assimilated. They have to inform us; we can’t effectively inform them.

I. Civilization & Primitivism

The first broad distinction between psychologies that Jung makes can be called primitive and civilized. Jung found that certain peoples were incapable of abstract thinking: their perception of the world is entirely literal. In a series of lectures given to the Tavistock Clinic for Medical Psychology, he describes a visit he made to the Pueblo Indians of the Southwestern United States. One of the Indians described to him their traditional religion, which is centered around the worship of a Sun God. The Pueblo pointed to the sun and said, “There he is.” Jung, curious, inquired whether or not the sun mightn’t literally be the deity himself, but rather that the sun possesses certain qualities associated with the Divine—perpetual death and rebirth, the warmth of paternal love, the light of heavenly knowledge. This was all incomprehensible to the Indian.

There is a certain online political quiz, called the Political Compass, which most of the readers of the Sydney Traditionalist Forum will likely be familiar with. One of the propositions is, “There are no savage and civilised peoples; there are only different cultures.” The supposedly right-wing response is “disagree”, where the left-wing response would be “agree”. But the term savage is more of a valuation than an observation. If one says, “The practice of sun-worship is savage”, they probably have something rather resentful in mind—a strong elitism or ethnocentrism or something of the sort. But to say, “The practice of sun-worship is primitive”, would be to make more of an observation about the evolution of human civilization. Jung doesn’t say that something being primitive therefore makes it wrong or bad. As he later says, “Nature commits no errors. Right and wrong are human categories.”3 That some people think in abstracts and others do not isn’t to say Civilized is necessarily superior to Primitive. But there is a clear distinction that we could only deprive ourselves by ignoring.

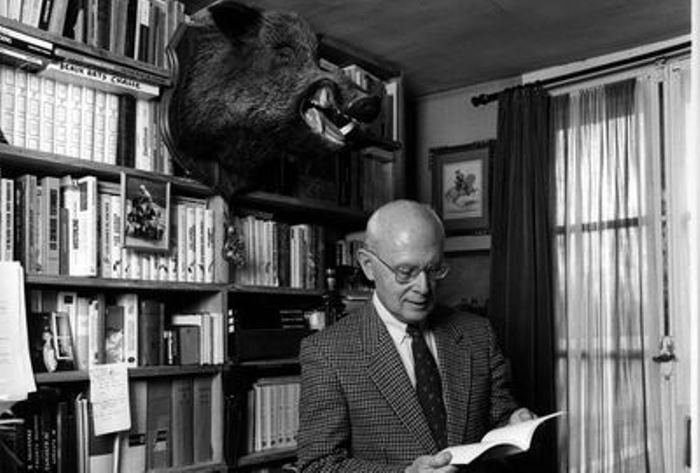

Carl Jung (1875 – 1961)

He goes on to make a further observation that I won’t dwell on for too long. In his travels around Europe, Africa, and Asia, he thought it well to distinguish three levels of cognitive development. Jung found that natives of Africa tended to think with their “bellies”—they were primarily concerned with obtaining those things essential to their bodily wellbeing. This would make sense according to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which at least points out that human beings prioritize essentials like food, water, and reproduction before they move into fields like science, theology, philosophy, and the likes. The next level of cognitive evolution he found represented in the Pueblos, who think with their “hearts”. He drew parallels between the Pueblo mind and the sort of thought characterized by Homer. The Pueblos are renowned for being heavily settled when compared to many Native Americans, and their relative sufficiency has offered them a chance to develop “intensity of feeling”—a sort of spiritual emotiveness. Lastly, Jung identified the White, or ultimately civilized, way of thinking, in which he largely included Asian peoples. These, he recognized, localized most of their psychological activity in the brain, which allows them to think in abstracts. In regard to Asians, he went so far as to say that the Indians and Chinese are readily conscious of what psychoanalysts would spend months trying to dig out what a European or American suppresses.

It’s unlikely that these sorts of finding would be received with anything but jeers by our 21st century contemporaries, though as far as I know they haven’t been disproven, only branded heretical and burnt. This is for future researchers to disprove if their findings conclude as much. We only have the product of Jung’s far-reaching fieldwork, as well as that of his contemporaries (including Freud) who pioneered Evolutionary Psychology and came to generally similar conclusions. Opponents of Evolutionary Psychology have waged a long war against what they call the “unethical” implications of the discipline, such as findings that imply the “naturalness” of gender, racial, class, ethnic, and other inequalities. Evolutionary Psychologists have defended themselves by pointing out that these realities don’t necessarily demand moral endorsement—as they might say, don’t confuse “is” with “ought”—but critics continue to decry the whole field altogether. For the life of me I can’t see how we’d benefit by ignoring certain scientific facts because they seem inconvenient to a preconceived ideology, but I won’t inflate my expertise in this area. These are only the facts, as I understand them.

II. Material & Spiritual Dispositions

Within the realm of the “civilized” mind there are two dispositions that Jung identifies. One is the Spiritual; the other is the Materialist. To carry on from our last discussion, it might simply be said that those with a Materialist disposition can think in abstracts, but choose not to. Let’s put it this way:

A. John Marmon, a Laguna Pueblo, looks up at the sun and sees the Divine.

B. Carl Jung, a man with a Spiritual disposition, looks up at the sun and sees a personification of qualities attributed to the Divine.

C. Sigmund Freud, a man with a Materialist disposition, looks up at the sun and sees a ball of hot gas and gooey metal.

Type B and C both represent Civilized thinkers. We might be inclined to draw parallels between type C and type A on account of their literalism, but the odds are someone who understands the chemistry behind the sun could grasp its basic symbolism.

But Jung is quick to assert that a spiritual philosophy doesn’t necessarily underlie a spiritual disposition, or a materialist philosophy a materialist disposition. Take the example of fanaticism:

“Fanaticism,” Jung says, “is always a sign of suppressed doubt.” Now, we shouldn’t read “fanaticism” as “extremism”, or “suppressed” as “secret”. A fanatic, as they say, is someone who can’t change his mind and won’t change the subject. There are two examples that come to mind of non-extremist conservatives, and on the issue of homosexuality. On the one hand, we have Roger Scruton, who said,

I took the view that feeling repelled by something might have a justification, even if it’s not a justification that the person themselves can give. Like, we’re all repelled by incest – well, not all, but most people are. And there’s a perfectly good justification, if you look at it in terms of the long-term interest of society. And in that essay I experimented with the view that maybe something similar can be said about homosexuality. And I don’t now agree with that, because I think that – it’s such a complicated thing, homosexuality. It’s not one thing, anyway. So I wouldn’t stand by what I said then.4

Roger Scruton, British Philosopher and Political Theorist

Scruton, evidently, can change his mind and the subject. Many Conservatives I’ve spoken to about this particular interview think Scruton exemplifies a lack of conviction. Maybe in a sense that’s correct: he’s not fully convinced by either argument. But it’s not likely that the most controversial thinker of the 21st century changed his mind because he’s timid or uninformed.

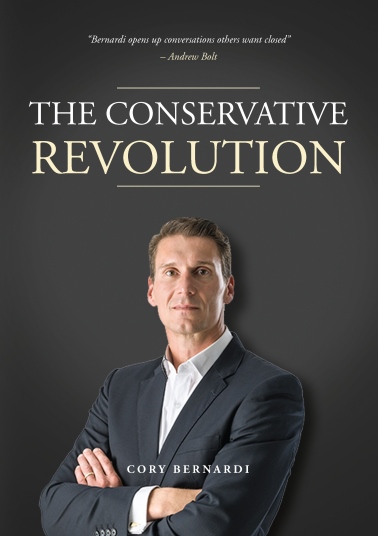

On the other hand, there’s been the huge outcry against Australian Senator Cory Bernardi regarding his new book, The Conservative Revolution.5 A thorough and far-reaching manifesto for modern Conservatives, Sen. Bernardi has very strong convictions on the issue of gay marriage. But claims that he’s “obsessed” with gays are proffered by onlookers who must be blissfully unfamiliar with either Sen. Bernardi’s career or the book itself. Of the dozens of issues he speaks about, those related to homosexuality are a very small portion. His views, which may be called “extreme” (though a decade or two ago they’d probably be called “average”) are not fanatical. He hasn’t changed his mind, but he’s happy to change the subject. The same can’t be said for his critics, with their pathological interest in Mr. Bernardi’s ideas about sex. Anyone who reads a 178-page book and can only find a chapter’s worth to discuss is a fanatic.

Senator Cory Bernardi.

I’d argue that Scruton and Bernardi offer examples of the two distinct “dispositions” highlighted by Jung. Scruton, as a philosopher, concerns himself with spiritual wellbeing; Bernardi, a politician, discusses more the sociological/political implications of homosexuality. That’s not to say Scruton is a “believer” and Bernardi isn’t, but we can tell where these two gentlemen’s priorities lie. From what I understand, Sen Bernardi is a more traditionally “religious” than Scruton, as Mr. Scruton’s defense of the Church of England, Our Church, was accused of emitting whiffs of agnosticism. And yet the disposition seems rather clear. One is concerned with the Spiritual; the other, the Material. The Spiritual thinker only happens to be less “traditional”, both on the issue of gay marriage and perhaps regarding religion in general, than the Material. Thankfully, we need both.

While Jung is disinterested in whether the Spiritual or the Material is “better”, and would have likely claimed that a person’s disposition is not up for scrutiny, we do have empirical proof that Spiritual dispositions do exist. Neither a theocratic nor a purely secular society would fulfill the psychological needs of all Civilized persons. This is, again, only the scientific reality.

III. Religion

In a report published by EWTN, the Roman Catholic television network, reporter Paul Likoudis wrote,

It’s certainly one of the most bizarre developments in 20th-century Catholicism that Carl Gustav Jung, dedicated to the destruction of the Catholic Church and the establishment of an anti-Church based on psychoanalysis, should have become the premier spiritual guide in the Church throughout the United States, Canada, and Europe over the last three decades. But that’s the case.6

Mr. Likoudis is correct; Jung has been taken up by Roman Catholic clergy and laypeople with immense enthusiasm. But he is shockingly incorrect in attaching any anti-Catholic sentiment to Jung’s work.

Jung was, in fact, far from being an anti-Catholic. In a survey he conducted, Jung found that 20% of Protestants he polled would go to a parson for psychological help, while 60% of Catholics opted for their priest. Furthermore, he noted that many of his Jewish and Protestant patients in Switzerland ultimately joined the Roman Catholic Church, while the English Anglicans he treated became drawn to the Anglo-Catholic movement.7 This neither surprised nor deterred him. On the contrary, he found the Catholic churches to be very much aligned with his own aims and methods:

What are we doing, we psychotherapists? We are trying to heal the suffering of the human mind, of the human psyche or the human soul, and religion deals with the same problems. Therefore our Lord himself is a healer; he is a doctor; he heals the sick and he deals with the troubles of the soul, and that is exactly what we call psychotherapy.8

He, of course, isn’t hostile toward religion at all. In the above quote, he even seems to identify himself as a Christian.

Jung called religion a “psychotherapeutic system”, which will jar a person of Faith in the same way he might recoil by being told that religion is a way of coping with the emptiness in our lives. Yet, that’s exactly what it is. Roman Catholics as eminent and traditional as Evelyn Waugh came to the Church by the realization that life is “empty and meaningless” without God. We would simply choose to give Jung as a scientist less credit than Waugh as a strict believer. If religion is true, it most certainly is a coping mechanism—and a very powerful one.

Maybe the easiest way for a person of Faith to look at this issue would be: “The soul is not the same thing as the brain. If we can think about and discuss spiritual experience, the brain and the soul must connect somewhere. Therefore, psychology and spirituality would necessarily overlap.” It’s not for me to say that this is necessarily the best way, but it’s certainly one way. It’s entirely plausible, then, that psychotherapy and religion could be “allied” in relieving the suffering of mankind. Jung’s ideas and practices especially are geared toward those of a spiritual disposition, regardless of their faith status.

Albert Camus (1913 – 1960)

Throughout his career, Jung has made a few remarkable comments about Catholic sacramental and liturgical theology—though he generally refrained from making value judgments about, say, transubstantiation and clerical celibacy. His focus is indeed more on how religious communities and rituals effect the health of the mind, and comes to some remarkable conclusions.

So, for example, we have Jung’s vindication of the confessional. “As soon as man was capable of conceiving of the idea of sin,” he wrote, “he had to recourse to psychic concealment—or, to put it in analytical language, repression arose. Anything that is concealed is a secret. The maintenance of secrets acts like a psychic poison, which alienates their possessor from the community.”9 Hell, said Sartre, is other people. The proven reality seems to be rather to the contrary: as the Christian has always known, Hell is being without any sort of consolation, anything to vindicate us from our insufficiencies. Our other arch-Absurdist, Camus, wrote in his essay Irony, about “… the horror of loneliness, the long, sleepless hours, the frustrating intimacy with God.” The solitary human soul is inconsolable. But Jung recognizes an alternative:

To cherish secrets and restrain emotions are psychic misdemeanors for which nature finally visits us with sickness—that is, when we do things in private. But when they are done in communion with others they satisfy nature and may even serve as useful virtues … It seems to be a sin in the eyes of nature to hide our insufficiency— just as much as to live entirely on our inferior side.10

Here we have the question of Materialist vs. Spiritual disposition. Can the Sacrament of Confession, or the Protestant Call to Confession, be true in a sense other than the mechanical “Deus Vult” sense? Christians unfailingly claim that they feel unburdened by practicing confession, and Jung proves us with an excellent psychological explanation for this reality. The Materialist—whose religious form is the Literalist, being unable to see beyond metaphysical and historical metaphors in religion—will say, “No, there is no validity in what Jung says. Confession makes me feel better because God cleanses me of my sins.” The person of Faith with a Spiritual disposition, though, will readily understand this psychic and spiritual relief which occurs across theological and denominational boundaries.

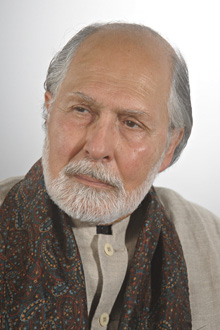

Joseph Campbell (1904 – 1987)

So much for confession. I’d like to cheat a little bit and turn toward Joseph Campbell, who, though a Mythologist by training, can hardly be excluded from the fields of theology and to a small degree psychology. His methods and discoveries find these three fields inseparable—just like Jung himself. In any regard he is heavily influenced by Jungian thought, and for this reason I think we can allow him to speak from the perspective of Analytical Psychology.

Campbell claims, “The real function of a church is simply to preserve and present symbols and to perform rites, letting believers experience the message for themselves in whatever way they can.”11 This would distress many Roman Catholics, who understand that the Protestant Reformation was an extreme interpretation of this idea. But this controversy might be evidence more of an overreaction on the part of the Church than a heretical confession by the Joseph Campbell, who is himself a Catholic. Seyyed Hossein Nasr, to return to the modern age’s greatest scholar of mysticism, believes that in the process of rebuffing the Reformation, Rome stunted its own rich mystical practice; the great vestige of Christian mysticism, he claims, is to be found in the Orthodox faith. I recently had an exchange with a convert to Orthodoxy, wherein I admitted my ineptitude at reconciling dogma with Communion in regards to liturgical practice. He reminded me that there is no Orthodox dogma that that isn’t derived from mystical experience. He was, of course, correct.

Traditional Roman Catholics are coming to the same realization, and in terms understandable to the Jungian. Campbell, for example, goes on to say,

… The Roman Catholic Church … has translated its Latin liturgy into local languages, thereby diluting or removing its essential mystery. When Catholics go to Latin Mass, the priest is addressing the infinite in a language that has no domestic associations; the people attending are thereby elevated into transcendence.12

Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Islamic Philosopher.

“Sacred languages” of this type have profound effects on the psyche, and survive also in Hinduism through Classical Sanskrit, in Judaism through Hebrew, and in Islam through Classical Arabic. (Much of Sufi literature, too, remains in the form of Classical Persian.) Religious communities are loathe to abandon these extraordinary forms, so fulfilling is the idea of a tongue reserved only for speaking to God. That this occurs across the “great religions” of the world is evidence of a highly civilized disposition toward religion—namely, the transcendence of the Divine.

Jung, too, knew these words, symbols, and rites had the dramatic effect of withdrawing the individual out of himself and into the community—out of his individual psyche and into the unconsciousness shared in common by his fellow practitioners. For this certain reason religion can never be entirely abandoned, nor can it be trivialized. Religion, in terms of psychological health, is a necessity that can never be reduced. It’s the most basic and enduring manifestation of catharsis, the technical term for confession, which is “no merely intellectual acknowledgement of the facts, but their confirmation by the heart and the actual release of suppressed emotion.”13 Religion, though often misapplied, is one of the surest means of sound mental health in the individual, and thereby essential to the health of society.

V. Sex & Gender

As we’ve seen, Jung discusses at length the relationship between the mind and the body. This distinction, he says, is a “false dichotomy”. Mind and body do not exist separately. He simply calls them the outer world and the inner world. The outer world we understand much better than the inner. In fact, we know relatively nothing about how the human psyche works, compared to how thorough our understanding of the body is. The logical way to proceed, then, with mind-body interactions, is to “proceed from the outer world inward.”14

This will prove relevant to questions of transsexualism and transgenderism. The dominant opinion is that, for instance, a man’s body with a female mind is female. This assumes an absolutely dominant position for the mind. No doubt this is done only for the best reasons, but the science of the psyche is, again, in its infant stages. We assume the mind of a transgender person is the best point of reference, and yet we know so little about the workings of that mind. It’s not for me to say, but I would be inclined to think Jung would caution against discrediting the body in an question of such stark, polar contradiction. We know what it means to have a male body; we know very little about what it means to have a male mind. Again, my professional standing in these issues is non-existent, but so long as sex reassignment surgery is being considered and oftentimes granted to minors and mentally ill adults, the “devil we know” isn’t the psyche.

While it would be unquestionably wrong to say that matters of mental health should be determined by political philosophy, one might be inclined to wonder why those who adhere to a Materialist and altogether secular philosophy would want to contradict this point. Lycanthropy—the delusion that a human is actually an animal—serves as a strikingly clear case of mental illness. As far as I can find, there are no experts who say, “Well, the mind knows best; this fellow much actually be a goose.” The same, we would think, should apply to Gender Identity Disorder, or gender dysphoria. But if we are, in fact, subjected to no forces but the chemical and the material, we can only come to one conclusion: if a person’s body is entirely comprised of male anatomical and chemical elements, but he believes himself to be a “female”, the dysfunction is that which contradicts the bodily reality.

I don’t know the reasoning behind the decision of the “Left” to air on the side of the psyche. I’d think it would be a combination of the availability of sex reassignment surgery—why bother treating the mind when the body can be altered?—and the oppressive amount of mental illness that plagues our society. To call GID a dysfunction of the body rather than the mind would be to eliminate about 700,000 persons who would otherwise be classified as psychotic. But again, that’s not for me to say. As we learn more about the workings of the mind, we may find that there’s a way to harmonize the “gender” of the mind with the absolute reality of the body in cases of GID. But that remains to be seen. It only appears that we have an overwhelming reason to be skeptical about relying on the mind to tell us about the physical reality of the body.

Jung’s Tavistock Lectures are rife with examples of other gender dysfunctions. The reader will no doubt be familiar with the many contradictory studies produced by psychologists, some saying that children fare best in a household where both biological parents are present, and others that say children raised by same-sex couples fare just as well (or, suspiciously, better than those raised by their biological parents). Jung died before same-sex parenting was even on the radar, let alone practiced. He does, however, point to examples where girls raised only by their father, and who effectively had no mother figure in their lives, were statistically more likely to experience gender dysfunction as well as other personality disorders. The same was true of men raised with no paternal presence. This research is abundantly available, so there’s no need to address this point at length. Simply, we might conclude, contrary to left-wing academia, that nature is not the only factor in gender identity—that nurture certainly plays a role.

Sigmund Freud (1856 – 1939)

What’s more pertinent is his ideas about the anima and the animus, which a surprising number of people who are totally unaware of Jung’s work seem to be increasingly familiar with. It’s no surprise that Jung and Campbell are drawn on heavily in the “Men’s Movement”, particularly the “Mythopoetic” camp. Jungian thought does not shy from the ideas of gender identities that are more than skin-deep. He affirms that a male form will correspond with a male psyche, and a female form with a female psyche. This, he claims, is the natural state; the influence of mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, etc. can only “nurture” the developing psyche poorly. So, in relation to the previous example, a boy only by his mother and three sisters will not have his psyche formed by feminine qualities, he will have his masculine qualities stunted. Jung also suggests that men be conscious of their recessive feminine element (the anima) and women of their recessive masculine element (the animus). These names are more esoteric than the concept that underlies them: this awareness simply suggests that the male and female psyche are not alien to one another, and the nature of the two genders exist within one-another. This would be familiar in the myth of Adam, from whom Eve was drawn directly. Within Adam there was enough “femininity” to create a woman, and within Eve was produced from the fullness of masculinity—yet the two are not identical. Those interested in Jung’s gender concepts might read his Alchemical Studies, which is another deceptively occult title for what is in reality an entirely empirical project. (Of course, alchemy was a science insofar as it was a success, and here Jung attempts to justify the ideals behind this forbidden science on a psychological, and does so with no small success.)

As a final note, the Conservative will also take some cynical humor from Jung’s take on our contemporaries’ fixation on sexuality in general, which is given to us by Freud’s sexual Pleasure Principle:

I could never bring myself to be so frightfully interested in these sex cases. They do exist, there are people with a neurotic sex life, and you have to talk sex stuff with them until they get sick of it and you will get out f that boredom. Naturally, with my temperamental attitude, I hope to goodness we shall get through with that sex stuff as quickly as possible. It is neurotic stuff and no reasonable person talks of it for any length of time. It is not natural to dwell on such matters.15

No doubt any traditionally-minded person will understand this component of our age’s “general neurosis”—the unsettling, tiresome, and unceasing dialogue about sexuality and gender. At heart, I find the Conservative’s dislike of the various Pride Movements relating to sexuality and gender is that they find nothing particularly interesting or valuable in the most intimate parts of other people’s lives. It does appear to be unhealthy, and to return to our Existentialist conversation, who could really derive meaning from their sexual or gender “identity”? The best and most altruistic Conservative, like the Jungian, would be more interested in bringing out more profound and enriching facets of human life. Sex is a reflex; along with food and seeking shelter, it’s one of the three fundamental acts of animal behavior. Only recently has it been considered worthy of celebrating, and not without great reservation. Conservatives (and many moderate Left-wing thinkers) maintain that purely physical properties cannot be elevated to the level of music, art, and other creative disciplines; they cannot inform public policy and institutions; and they cannot be equated with such ideas as “love” and “family” unconditionally. While it’s not for me to say whether the pro-sexual identity camp or the skeptics will win out in the end, the argument will ultimately be decided by a scientific understanding of human nature, and Jung has opened the door to an alternative to the Freudians’ pure physicalism.

VI. Morality

Jung isn’t going to give the hard-liner a psychological defense of traditional morality. He’s not going to say, “Abortion is psychologically proven to be bad” or “Homosexuality is always damaging”. There are limits to his field, as there always are in science. But he does insist that morality is a very real and intuitive concept. In Existentialist terms, for many people, one’s moral character is as much a precondition of seeking fulfillment as one’s physical character.

In the Tavistock Lectures, Jung recounts a young man who came to him feeling mentally burdened. The young man had prepared a list of potential causes according to the Freudian model. Jung said something to the effect of, “Well done! So if you’ve identified the problem and are willing to admit it, why is it still troubling you?” The young man didn’t know, which is why he’d come for analysis. As they went deeper into the therapy, Jung deduced the discord had something to do with the young man’s living situation: he was sleeping with an older woman who gave him a fair amount of money to play around with. When Jung asked whether this might be the source of his anxiety, the young man refused to accept that it might be. Ultimately he gave up on Jung as a therapist, and the issue remained unresolved. Evidently the young man, despite his intellectual assent to “modern” ideas about sexuality and morality, was nonetheless unconsciously burdened by the arrangement.

In the Tavistock Lectures, Jung recounts a young man who came to him feeling mentally burdened. The young man had prepared a list of potential causes according to the Freudian model. Jung said something to the effect of, “Well done! So if you’ve identified the problem and are willing to admit it, why is it still troubling you?” The young man didn’t know, which is why he’d come for analysis. As they went deeper into the therapy, Jung deduced the discord had something to do with the young man’s living situation: he was sleeping with an older woman who gave him a fair amount of money to play around with. When Jung asked whether this might be the source of his anxiety, the young man refused to accept that it might be. Ultimately he gave up on Jung as a therapist, and the issue remained unresolved. Evidently the young man, despite his intellectual assent to “modern” ideas about sexuality and morality, was nonetheless unconsciously burdened by the arrangement.

The defiant Materialist would claim that this was the result of thousands of years of conditioning which the young man couldn’t separate himself from. Perhaps they’re right. But perhaps there’s also a deep-seated sense or right and wrong—an objective conscience—that exists within human beings innately. We can only speculate; but, considering this has been the dominant point of view for most of human civilization, it may be best to assume that there is such a thing as a conscience rather than abandoning the idea altogether. We might even be bold enough to say that our traditional sexual and relational mores really are a result of an intuitive guiding force rather than just another option for contracting between individuals.

VII. Closing thoughts

If you’ve suffered through this entire article, I’ve only one more thought to offer. However much uncertainty Jung confessed in his own work, I must confess to even more. None of this research is my own; I’ve drawn none of these conclusions. It wouldn’t be my place to say that all of Jung’s findings are correct or absolute. Even as he said, “My methods to not discover theories, they discover facts,” so too do I only hope to have given the reader some facts to consider.

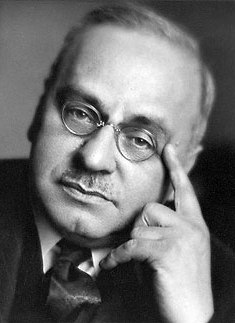

Alfred Adler (1870 – 1937)

However, I would like to make one point clear, and with certain conviction: it would be disastrous for any sort of power elite,—be they political, academic, scientific or cultural—to simply discard Jung’s findings. It would do immeasurable damage to decide that there is no spiritual component to human beings and enforce a strictly Materialist society. There is an undeniable Spiritual, even a religious, component to human beings, and we can’t assume that a purely material, secular society would be satisfying for each individual. We should take great interest in the contrast between Jung’s admission that there are indeed people with a Freudian psychology who are driven by pleasure, as well as those with an Alderian psychology (identified by the Austrian psychotherapist Alfred Adler) who are driven by power. Jung identifies the “Jungian” type:

As a rule people who have reached a certain maturity and who are philosophically minded and fairly successful in the world and are not too neurotic, tend to agree with my point of view.16

Compare this to Freud’s introductory lectures on psychoanalysis to the University of Vienna, where he gives his students such edicts as, “Psychoanalysis is not to be blamed for [a certain] difficulty in your relation to it; I must make you yourselves responsible for it, Ladies and Gentlemen…” In other words, these theories which Freud has discovered are absolute, and should you reject it, that is your deficiency. This, Jung proves, is incorrect. Freudian psychologies exist, but not exclusively. We face the modern crisis of secular absolutism because of these proclamations, which a society composed of healthy individuals cannot endure.

I encourage any reader to pick up one of Jung’s books; The Undiscovered Self is a short and powerful introduction to his ideas concerning society. This article has also avoided entirely what is arguably the most important facet of Jung’s work: dream analysis. Indeed, this will hardly serve as any decent introduction to Jungian thought, but I hope it might accomplish two goals: the first, to challenge the myth that psychology always and everywhere results in a materialist outlook, and the second, to spark interest—however small—in the ideas of one of history’s greatest minds. If either of these are accomplished, dear reader, I can hope the time you spent reading this was spent well.

– M. W. Davis

The author is a native Bostonian currently studying at the University of Sydney. He is an officer of the Australian Monarchist League. His personal blog is “The American High Tory”.

End notes

- C. G. Jung, W. S. Dell, and Cary F. Baynes, Modern Man in Search of a Soul (Routledge, 2001) p 48.

- Ibid p 62.

- C. G. Jung, Analytical Psychology, Its Theory and Practice (Pantheon, 1968) p 95.

- Aida Edemariam, “Roger Scruton: A Pessimists Guide to Life” The Guardian (online) (5 June 2010) (accessed 18 February 2014). Print edition not available to the writer.

- Cory Bernardi, The Conservative Revolution (Connor Court, 2013). For more about the controversy, see: Luke Torrisi, “First ‘Shots Fired’ in Australia’s Culture War” SydneyTrads (12 January 2014) (accessed 18 February 2014).

- Paul Likoudis, “Jung Replaces Jesus in Catholic Spirituality” EWTN online library archive (undated) (accessed 18 February 2014); it is noted op cit that this article was originally published in The Wanderer (5 January 1995).

- Jung, Analytical Psychology p 181.

- Ibid.

- Jung, Modern Man p 31.

- Ibid p 35.

- Joseph Campbell (Eugene C. Kennedy, ed.), Thou Art That: Transforming Religious Metaphor, (New World Library, 2001) p 29.

- Ibid p 33.

- Jung, Modern Man p 36.

- Ibid p 77.

- Jung, Analytical Psychology p 25.

- Ibid p 143.

Most of what you say about Jung here I think he would agree with. But I have to point out that what liberals object to and act out against is the persecution of individuals for their sexual preference, the punishing laws and conventions that bind an individual against what only they can know is their nature. Those gay pride marches you mention exist to garner attention to this issue. It’s politics, an awareness that comes with sharing space in the polis.