“The humanism of the Renaissance was a protest against the excesses of the ascetic. Now that science aspires to be all in all, somewhat after the fashion of theology in the Middle Ages, the man who would maintain the humane balance of his faculties must utter a similar protest against the excesses of the analyst, in whom a ‘literal obedience to the facts has extinguished every spark of that light by which man is truly man.’ It is really about as reasonable to use a dialogue of Plato merely as a peg on which to hang philosophical disquisitions as it was in the Middle Ages to Ovid’s ‘Art of Love’ into an allegory of the Christian life. In its mediaeval extreme, the human spirit strove to isolate itself entirely from outer nature in a dream of the supernatural; it now tends to the other extreme, and strives to identify entirely with the world of phenomena. The spread of this scientific positivism, with its assimilation of man to nature, has had especially striking results in education. Some of our higher institutions of learning are in fair way to become what a certain eminent scholar thought universities should be, – ‘great scientific workshops.’ The rare survivors of the older generation of humanists must have a curious feeling of loneliness and isolation.”

“The humanism of the Renaissance was a protest against the excesses of the ascetic. Now that science aspires to be all in all, somewhat after the fashion of theology in the Middle Ages, the man who would maintain the humane balance of his faculties must utter a similar protest against the excesses of the analyst, in whom a ‘literal obedience to the facts has extinguished every spark of that light by which man is truly man.’ It is really about as reasonable to use a dialogue of Plato merely as a peg on which to hang philosophical disquisitions as it was in the Middle Ages to Ovid’s ‘Art of Love’ into an allegory of the Christian life. In its mediaeval extreme, the human spirit strove to isolate itself entirely from outer nature in a dream of the supernatural; it now tends to the other extreme, and strives to identify entirely with the world of phenomena. The spread of this scientific positivism, with its assimilation of man to nature, has had especially striking results in education. Some of our higher institutions of learning are in fair way to become what a certain eminent scholar thought universities should be, – ‘great scientific workshops.’ The rare survivors of the older generation of humanists must have a curious feeling of loneliness and isolation.”

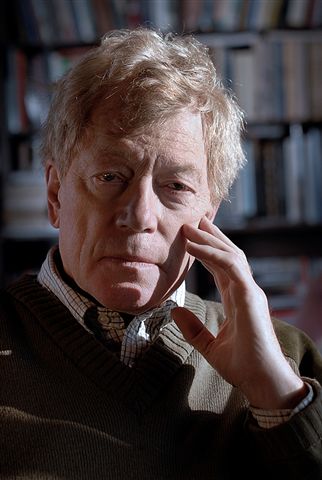

▪ Irving Babbitt, Literature and the American College (National Humanities Institute, 1986) extract from page 119.

Be the first to comment on "Quote of the Week: Irving Babbitt, “Literature and the American College”"