Conservative Prospects

in the Second Age of Malcolm

Part Three

VI

The need for a social movement cannot be merely posited; its need has to be found out through weighing up the alternatives. Such a weighing up, as the two preceding parts to this presentation show is based on historical experience, of what has come before.1 One could also use the evidence of the American conservative movement, where a direct analogy to the experience of libertarian and paleoconservative co-operation can be made with the idea of what is referred to among various non leftists within the Liberal Party as the ‘broad church.’ As many veterans of the US fusionist and related experiments attest, it did not work very well at all,2 and had observable disastrous results earlier than what we see here in Australia. Such a case study is needed, but it is not sufficient. The use of Australian examples is required for Australian conservatives’ edification.

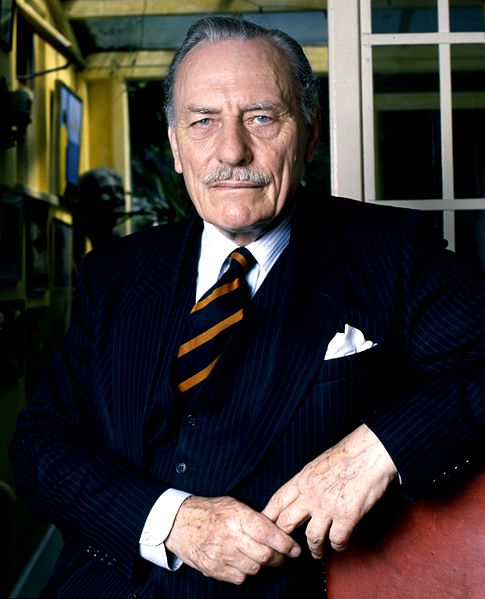

Enoch Powell (1912 to 1998)

These arguments have been made in the past, but like Cassandra, their expositors were not heard; such is the power of emotion. The attachment that people have had for political heroes and their party has made it near-impossible for reason to be heard. But now that hold has weakened with the confluence of the Federal and several State divisions of the Liberal Party being fronted by implicit or even explicit leftists. There appears to be room for alternative suggestions and arguments necessary to secure the future of conservatism in this country. Although this may be tedious to those who have come to these conclusions already, there is merit putting these alternative views on the record for the benefit of the present young vanguard of conservatism as well as for the future leadership cadre of traditionalist (or at the very least, non-leftist) politics in Australia.

In the context of recent events, leaving or staying in the Liberal Party is an emotive act on the part of the core conservative membership. Both are expressions of anger at the direction of the contemporary party establishment, with the latter being tinged with feelings of loyalty to the party as such, or even spite towards its mendacious current leadership. Anger can dissipate just as quickly as it came, especially in today’s 24 hour news cycle where the outrage that gave rise to such a feeling can be quickly forgotten as the story is buried in the frivolity that passes for current affairs. Even if the reason for anger is not forgotten, this emotional basis for action is not a sustainable motivation for the long term. For reaction to be based on emotion alone, there can be no possibility of coherence in strategy and vision because there is a lack of ideational content. This is the cause of small parties that eventually become stagnant and rendered terminal by merely populist leaders.

Carl Schmitt (1888 to 1985)

Populist leaders do not in fact lead, but are spokesmen for the populist reaction. As such they are in concert with the feeling of those that look to them for direction, but do not shape it in any concrete fashion. At best, such leadership raises awareness for important issues sidelined by the established parties and the media. Thus, those that find themselves as populist spokesmen are to be congratulated on their courage in speaking up where others remain silent, but in becoming the focus of reaction they exacerbate the problem of its emotive basis. Only self-conscious leadership can offer a way out of the vicious cycle of right-wing politics in Australia. Self-conscious, because it is aware of conservative principles and therefore will know what needs to be upheld, promoted and defended, as well as what must be outright opposed. This is not to advance an elitism disconnected from the every day concerns of the base, but the leadership’s model will be Enoch Powell rather than Pauline Hanson. In his speeches, Powell who was a Classicist of the highest order, clearly understood and appreciated the concerns of his constituents and therefore truly represented Britons’ interests.

Such leadership will not exclusively concern itself with the arcane matters of the academy but also look to foster human relationships. The connexions made in political parties can be little more than those of momentary convenience or reflect passing social fads. Indeed there are some that vulgarise Lord Palmerston’s maxim that “we have no eternal allies…our interests are eternal and perpetual” to a personal code, where man as an island is substituted for the island nation of Great Britain and “interest” is taken to be unenlightened self-interest. In such an environment, there is little wonder why conservatives would haemorrhage potential talent to established networks. A social movement that not only looks to intellectual formation but also social bonds can stop such attrition. It is often a solitary life for conservatives, not being able to speak their mind freely in every-day interactions for fear of committing thought-crime. Something as seemingly trivial as a monthly drinks night is just as important as a reading group as it will contribute to a greater feeling of camaraderie and common purpose among conservatives. If the conservative movement cannot promise a cushy job, it can at least give the victims of atomisation a sense of genuine fellowship.

The nature of a social movement is that it favours a horizontal rather than vertical integration of its members. It can diffuse itself over the many aspects of life. It is horizontal because its sole criterion is adherence to principles, thus any number of groups or organisations can be included within it, and this is crucial. As the Left are hegemonic in every sphere, in business, government, academia, culture, so too must the fight against them be on every front their influence is felt. This is the failing of the establishment right, who think only in crude economic terms; the irony being that not even dialectical materialists think in such a conventional Marxist frame of mind where the base determines the superstructure; hence Cultural Marxism being the ideological victor over the past half century. It becomes apparent that on this model it matters not whether conservatives found a new party or stay inside the Liberal Party. Both could be options for different groupings within the broader social movement, working in tandem, and never forgetting that it is principles that comes before all else. Yet, party politics is a secondary concern in this picture, and should develop organically. We are in a similar position to the dissidents in the former Eastern Bloc, where negating ideology whilst participating in the social and cultural life of their communities was the only viable option. History has vindicated this approach, showing us that principles precede parties.

Joseph de Maistre (1753 to 1821)

If the crisis of Australian conservatism is due to a forgetting of conservative principles, then rediscovering such principles is the primary task for the leadership of the coming conservative movement. The movement must endeavour to understand what went wrong after Menzies retired from public life. If there was nothing glaringly incorrect in Menzies’ articulation of conservative principles in the Australian context, but rather it was human weakness in straying from these principles, the question then becomes one of the possibility of returning to such principles. This is so because the world that the establishmentarian ‘right’ has allowed the Left to develop (whilst they were sleeping at their posts or actively colluding with the enemy) is vastly different to the one Menzies inhabited. Australian conservatism as articulated in the 1940s, although based on solid foundations, is rooted in a world that has largely past and its particular articulation may not be possible in the world we live in today. However, the leadership must turn to the whole of Rightist thought in addressing this question. If, as we have sought to demonstrate, Australian conservatism is not merely a moderate and liberal position, then its affinity with other schools of Rightist thought must be seriously considered. Perhaps even a passage written by Joseph de Maistre or Carl Schmitt might rescue Australian conservatism and contextualise it for the 21st century.

Cory Bernardi has sought to offer a solution to this problem in his book The Conservative Revolution (2013), where conservative principles are used to demonstrate what a particular instantiation for an Australia in the 21st century could look like. A quick perusal of the first chapter alone demonstrates Bernardi’s firm grasp of conservative thought in the Anglosphere, citing British traditionalist conservatives and American paleoconservatives alike.3 This approach was picked up by Edwin Dyga in his October 2014 Quadrant article “The Future of Australian Conservatism.”4 In what is a review, on first blush, of Bernardi’s book becomes a much wider ranging and important essay to the attentive reader. Dyga looks to the positions advanced by Bernardi and finds their antecedents and contemporary expositors in a broad sample of Rightist thought. Identitarians and thinkers associated with the European Nouvelle Droite are shown to bear relevance to our Australian context in the here and now. This is what conservative leadership looks like, and it shows us that not only do principles precede parties, but they are also above them.

VII

Our inherited British history is replete with examples of conservatives breaking with parties over matters of principle. There are the Ultra Tories in the 1820s, and the Adullamites within the UK Liberal Party opposed to the second Reform Act in 1868. The Adullamites were named after a Biblical reference to the cave of Adullam, where David’s followers sought refuge. Where these historical examples differ from us is in the nature of their reaction. Although they were not based in emotion, but on principles, they were uncritically so, lacking self-consciousness. When an institution or practice becomes moribund, it becomes ‘conservative’ to cast off the offending branch rather than let it rot the entire organism. What appears to be compromise in principles is then the prudent course of action. Our situation is different, it is not we who have forgotten principles but the Liberal Party. Their compromise is not prudential but suicidal, and not just for Australian conservatism but for Australia as a whole. In the establishment right’s betrayal of the Australian People and Nation, our reaction becomes our moderation, as it is they who have strayed too far to the Left.

Our reaction will take place in our own Caves and Enclaves, maturing under consideration of principles and their future applicability, before organically developing into political representation.

[Return to Part One | Part Two]

– Morgan Qasabian is a student of history and philosophy and a long time conservative activist.

Endnotes:

- See further by this writer: “Conservative Prospects in the Second Age of Malcolm: Part I” SydneyTrads (17 October 2015) <sydneytrads.com> (accessed 17 October 2015) and “Conservative Prospects in the Second Age of Malcolm: Part II” SydneyTrads (17 October 2015) <sydneytrads.com> (accessed 17 October 2015).

- From a more contemporary paleoconservative perspective, see: Joseph Scotchie (ed.) The Paleoconservatives: New Voices of the Old Right (New Brunswick: Transaction, 1999).

- Cory Bernardi, The Conservative Revolution (Ballarat: ConnorCourt, 2013) pp. 6–20.

- Edwin Dyga, “The Future of Australian Conservatism: Mainstream or Sidestream?” Quadrant, Vol. 58, Issue 10 No. 509 (October 2014) pp. 46–58.

Citation Style:

This article is to be cited according to the following convention:

Morgan Qasabian, “Conservative Prospects in the Second Age of Malcolm: Part III” SydneyTrads – Weblog of the Sydney Traditionalist Forum (17 October 2015) <sydneytrads.com/2015/10/17/2015-symposium-morgan-qasabian-pt3> (accessed [date]).

Leave a comment