Conservative Prospects

in the Second Age of Malcolm

Part One

I

On 15 September this year, a left-wing Prime Minister was sworn in. The 29th Prime Minister of this Commonwealth of ours, and the fifth in five years. This was done without a single ballot being cast by the public, instead being decided in the party room of the governing Liberal Party. This is truly a feel-good moment for the political class of Australia. Cathartic even. Those battlers have come full circle since the days of the failed republican referendum where the politicians’ republic was given to the public to vote on, so that they may vote away their ability to have a say in the highest electable office in the country. Of course, this is not a novelty, nor is the Liberal Party advancing the avant-garde in Machiavellian machinations. Labor got there first, but this time it is all that more special considering it was the leader of the failed referendum who bypassed the many to leapfrog into the Premiership, Malcolm Turnbull. There is no other man more hubristic in his disdain for the Australian people than Turnbull, and where there is hubris, nemesis is sure to follow. What will this downfall look like? Will it be the personal downfall of Turnbull? After all, Turnbull is a left-wing leader of a nominally right-wing party; the voting base will not stand for it. I do not think Turnbull will be affected by this nemesis that is his due; instead it is the future of the Liberal Party and its relationship with Anglo-Australian conservatism that is at stake.

II

Australian politics since Federation has been Labor vs. non-Labor. Non-Labor in this equation has been settled as the Coalition of the Liberal and National Parties, and has been this way for the last seventy years. This divide is predicated on the more fundamental left-right split, Labor being on the left and the Coalition, allegedly, on the right. In a time when the Liberal Party has a left-wing leader—who would be far more comfortable in the Labor Party had he been able to secure a seat—this equation has been upset.

On one interpretation of recent events, there now may as well be two Labor Parties, one old and one new. It is this new one that is the current darling of the Media. Indeed, the ABC is hopeful that their good buddy Mally will reverse the $250 million reduction in funding Tony Abbott initiated, with an unnamed Liberal Party source stating that “there will be no more culture wars.”1 The Herald really does need to check their sources, as the future tense implied in this statement is several decades out of date. Unless the unnamed source is acknowledging not only the conservative loss of the Culture War but also that the leftist-clothed-as-rightist at the helm of the Liberal Party will be doing the Australian Left’s bidding.

Am I being unfair? Abbott himself has said that there has not been any change in policy from his government and the one now led by Turnbull. This is of course very far off the mark. Let us begin with Turnbull’s remarks about what kind of government he will lead: “This will be a thoroughly Liberal government. It will be a thoroughly Liberal government committed to freedom, the individual and the market.”2 The transcript is being rather coy in capitalising the word “liberal.” From the context of the press conference it was very clear in what sense of this equivocal—in our context— word was being used by Turnbull.

Minister for Foreign Affairs, Julie Bishop

Turnbull intends the public to think he means the small “l” word, in the above, of a classical vintage. That would not be so bad, as the Australian nation was able to prosper under such liberalism. That is, until the latter half of the twentieth century when it morphed with Western Marxism and became the system which we labour under presently. It is this hybrid left-wing capitalism that is the real substance of what Turnbull means by “liberal.” This is not mere assertion; it can be corroborated in Turnbull’s deputy, Julie Bishop’s words to the UN regarding climate change (what used to be vociferously declared “global warming” not too long ago). According to Bishop the Turnbull government is “committed to ensuring the United Nations climate conference in Paris at the end of the year is the platform needed to secure a collective approach to the below 2 degree goal.”3 One of the only achievements of the regretfully forgettable Abbott government that conservative and right-liberal media pundits can point to is the scrapping of the Carbon Tax. Even the most unreflective Coalition voter would agree that Bishop’s words portend a flagrant reversal of the previous government’s policy.

The national left had imposed the Carbon Tax on Australia, and now the notional “right” is imposing the dictates of the international left willingly. And make no mistake; this climate conference is ideologically of the left. It is intended to legally bind every nation without the possibility of withdrawal from the treaty, with the onus placed on developed nations (specifically, Europe and European descended settler nations), allowing the rest of the world leeway to continue polluting at the unprecedented rate that they have been. After all “the needs and capacities of each country” are to be taken into account. Naturally wealth redistribution from the West to the rest of the world is a part of this “solution.”4 Indeed, this is no solution to environmental degradation but instead the solution to the problem of the death of the old god of the left, Marxism.

Why then is a notionally right-wing government supporting such a measure? It is not just from a conservative perspective that this can be opposed, but also from a classical liberal one; which Turnbull signals to the public he adheres to. As we have seen, with this single policy change alone the Liberal Party has shifted further to the left. Such a shift can be only the result of a lack of understanding on the fundamentals of political philosophy, and conservative principles in particular. Earlier it was said that the party system in Australia was based upon such fundamentals, and although this presentation is not intended to be a work of political theory, it behooves us to briefly deal with such theoretical matters as they underwrite the practical solutions to the present crisis in the Liberal Party.

III

The principles of the Left can be deduced from what has already been said, they are universalist in nature, and misguidedly egalitarian. Using the example of the international Left’s co-option of environmentalism, the institution through which their will is to be enforced, the UN, is a one size fits all approach to political problems. The principle underlying this is universalism, all peoples and nations are interchangeable, and that being the case, such differences (i.e. borders and nations) are superfluous and can be disregarded. Inherent differences and particularities are simply ignored. An aggressive egalitarianism necessarily follows this position; if there are no differences then all people are equal in every respect; if they are not, they must be forced to be, or at least we must all be forced to believe that they are. This egalitarianism is shown in the wealth redistribution that the UN is seeking to impose on Australia. The Right’s principles are in opposition to the Left’s and in place of universalism is particularism. That is to say, the primary principle of the Right is the common good of a particular People and Nation. It follows from this that there are real differences between peoples, and thus the Right’s rejection of the Left’s coercive and fundamentally unnatural egalitarianism. A doctrinal anti-egalitarianism is not posited in its place, but rather equality or inequality is sought where one or the other will contribute to the common good of the community on a case-by-case basis. This is related to what Aristotle calls equitable justice in his still influential Nicomachean Ethics.5

Aristotle, as depicted by Michelangelo

According to Aristotle there is a specific sense of justice as a part of virtue, and justice as the whole of virtue. Justice as a part of virtue also points to two primary senses of what people mean by justice, political or what is lawful and equitable. The former does not concern us here, and with the latter it is again shown to be of two sorts, distributive or geometrical and a justice that gets things straight. The justice that gets things straight is in settling a dispute between parties where one has wronged the other, and when that dispute is adjudicated, the share each receives is equitable.6 Distributive justice concerns public honours and wealth and is distributed according to merit. It is called geometrical because of the ratio created by the parties involved as well as their relation to the goods being distributed. This ratio is equitable and just.7 The Left distort distributive justice, and either call their conception distributive or rebrand it as redistributive. For the Left, being egalitarian, the ratio must always be 50:50, regardless of merit. On Aristotle’s understanding this is unjust and inequitable. This is so because:

[I]f the people are not equal, they will not have equal things, but from that source come fights and complaints, whenever people who are equal have or are given things that are not equal, or people who are not equal have or are given things that are.8

Here we see one possible source for the Right’s view of equality, namely equality to equal things and inequality to unequal things.

This has not been an attempt at an exhaustive definition of the fundamentals of politics, but rather a definition of the (very) first principles of political labels and then an exploration of the philosophic basis. From this meagre delving into theoretical matters, we can already see that we are justified in stating that the Liberal Party is now a political vehicle of the organised left. If the party were founded on leftist principles this would not be a crisis, but the party has drifted away not only from conservative philosophy in the abstract but the particular manifestation of these principles in our Anglo-Australian context as articulated in the founding documents of the party.

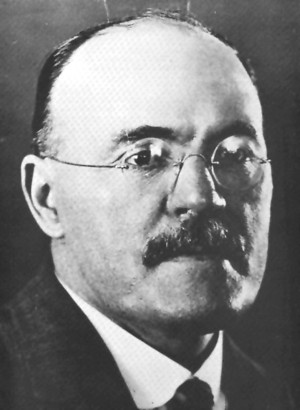

Sir Robert Gordon Menzies

The founding documents of the Liberal Party are the objectives of the party proposed at the inaugural party conference of October 1944, which were accepted in the constitution in 1945 and the Federal platform of 1946.9 In these documents we see conservative principles applied to policy points, and they are indeed conservative rather than liberal. Sir Robert Gordon Menzies envisioned the party to stand up for the common good of all Australians, whether working class or middle class. All economic policy statements were directed to this end. This is in stark contrast to the contemporary Liberal Party having recently negotiated free trade deals—that have thankfully yet to become the law of the land—which only enrich Big Business and drive down Australian wages, while flooding the market with poorly made cheap consumer goods. In Menzies’ view, being an Australian meant more than being an atomised individual who happened to have a particular stamp in one’s passport. An Australian was someone of Anglo-Celtic descent and those who had embraced this identity, rather than attempting to change it. It was to their prosperity that the Liberal Party was established.

Distributive justice is laced throughout these documents, and the concept of merit that determined equitable distribution of goods was the ancient yeoman ideal of living off the sweat of one’s brow. Aristotle shows us how different regimes will understand merit to mean different things where “those who favour democracy mean freedom, those who favour oligarchy mean wealth, others mean being well born, and those who favour aristocracy mean virtue.”10 The yeoman ideal of merit can be seen to be an instantiation of freedom in a particular Australian liberal democratic context. Thus the principles of Menzies are conservative principles for a liberal democracy in the Antipodes, and it is this that Menzies called “Liberalism”. Modern liberal democratic freedoms as well as ancient political freedoms coexist in Liberalism; freedom of speech and association are called for in the same breath as defending Australia from external aggression and exploitation.11 This makes Turnbull’s appropriation of Menzies’ Liberalism all the more galling, as it is the exact opposite of what was meant. The contemporary Liberal Party does not uphold the common good or freedom of the Australian people. Instead favouring the interests of international finance and Big Business, as well as the goals of the international left, i.e. the hybrid left-wing capitalist system. If Menzies’ Liberalism is the definitive statement of Australian conservatism then the crises of the Liberal Party is widened to the crisis of Australian conservatism as such.

When a conservative political party no longer adheres to conservatism, there remains two options for conservatives in regards to political representation, refound the party on such principles or establish a new explicitly conservative party. The second part of this article will weigh up the pros and cons of both positions and think through practical steps needed in either case.

[Go to: Part Two]

– Morgan Qasabian is a student of history and philosophy and a long time conservative activist.

Endnotes:

- Matthew Knott, “ABC hopes for funding boost as Malcolm Turnbull ends ‘culture wars’” Sydney Morning Herald (online) (24 September 2015) <smh.com.au> (accessed 10 October 2015).

- Transcript, Honourable Malcolm Turnbull MP and the Honourable Julie Bishop MP, Press Conference, Commonwealth Parliament House (14 September 2015) <MalcolmTurnbull.com.au> (accessed 1 October 2015).

- Stephanie J Anderson, “Julie Bishop pushes for restrained use of veto by members of United Nations Security Council” ABC News (online) (30 September 2015 @ 11:44am) (accessed 1 October 2015).

- See the “United Nations Climate Change Conference” website and in particular the “COP21/CMP11” tab (accessed 1 October 2015).

- All references to Aristotle that follow are made with the standard Bekker numbers and are from Joe Sachs’ translation of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics (Newburyport: Focus Publishing, 2002).

- Ibid. [1132a1–1132b20].

- Ibid. [1131a10–1131b30].

- Ibid. [1131a20–30].

- Both documents can be found in: The Federal Platform of the Liberal Party of Australia: Formulated by the Joint Standing Committee on Federal Policy at its meeting in Canberra in January, 1946 (Melbourne: The Party, 1946).

- Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, op. cit. [1131a20–30].

- It needs to be noted that the very first point of the Federal Platform (see supra 9) reads that the party stands for “full Australian participation in the United Nations Organisation and acceptance of the responsibilities arising under the Charter” (op. cit. p. 5). We must keep in mind that this was written in 1946 after two destructive world wars when there was hope that the UN would not contravene its founding principle of the self-determination of Peoples and Nations. Today we can see that it stands for its antithesis in the realisation of the universal and homogeneous state. If the Liberal Party advanced its founding principles, arguably, Australia would pull out of the UN and reserved a right to exit all treaties agreed to under subject to sovereigntist imperatives.

Citation Style:

This article is to be cited according to the following convention:

Morgan Qasabian, “Conservative Prospects in the Second Age of Malcolm: Part I” SydneyTrads – Weblog of the Sydney Traditionalist Forum (17 October 2015) <sydneytrads.com/2015/10/17/2015-symposium-morgan-qasabian-pt1> (accessed [date]).

Leave a comment