Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs

On Baudelairean Traditionalism

I

The Prelude

Edwin Dyga invites a response to the question, Whither Conservatism – or rather “Quo Vadis, Conservatism,” a nicely history-minded verbal construction that takes us backwards in time through Polish author Henryk Sienkiewicz’s novel Quo Vadis (1895) to the moment of intercessory locution by which God steered Saint Peter back to Rome to complete his mission there. While the question is Whither Conservatism, however, the occasion is a “Traditionalist Symposium.” I ask indulgence to use the first person, something that I inveterately enjoin my undergraduates not to do, just as a discipline, for the sake of familiarizing themselves with the grammar of objective judgments. Two decades ago I ceased calling myself a conservative. I began to prefer “reactionary” and after a bit “Traditionalist.” My motive was the conviction that whatever Conservatism had once promisingly implied, it had regrettably adjusted itself to the reigning super-conformity; self-anointing conservatives, it seemed to me, knew neither where they were going nor where they had been. They were simply going along – and like all people who are going along they were actually following the leader. They had become mindlessly modern, which means cultureless, historyless, and wisdomless. They stood for nothing because they knew of nothing for which to stand. I write in the context of the USA. Such names as George Herbert Walker Bush, George Bush, John McCain, Lindsay Graham, and John Boehner furnish the illustrative gallery for my thesis. If they were conservative, I reasoned, then I must be something else, because they stood exclusively for their re-election, with its perquisites; whereas I, running for no office and expecting no perquisites, stood for several somethings that bitter experience and a great deal of study had permitted me to define. The people claiming the title conservative seemed to me not even to be against anything. As much as they were following the leader, they were also drifting with the tide. The name of the tide is Modernity.

II

The Fugue

“Fugue” is a rich word. It has a primary musical meaning – it is a procedure, much more than a form, by which successively entering voices intone the theme, as though they were trying to steal it from one another, resulting in an increasing thickness or complexity of the texture. Other developments occur: The competing voices savagely draw and quarter the theme, reducing it to the fragments of its constituent elements, its basic intervals and motifs; the competing voices also perform Torquemada-like tricks on the theme, inverting it, reversing it, and inverting the reversion, all the voices shouting (as it were) all at once, in what is called the stretto. The stretto typically resolves itself by bringing back the theme, with the note-values augmented, in the form of a chorale. A musical fugue resembles nothing so much as a sacrificial orgy in which the crowd picks on some helpless victim to be its scapegoat, with the usual outcome of lynch-mob activity. The chorale would represent the crowd’s Dionysiac conviction that in expelling evil from its midst it had acted in a fully justified because Godlike capacity. It is extremely significant that fugue has its origins in Northern Europe during the culminant phase of the Reformation – the Thirty Years’ War. Fugue also has social and psychological meanings wherein it refers to the catastrophic breakdown of the community and the sustained panic of the now atomized and thoroughly confused and frightened people. Musical fugue is a symbol of crisis. The Reformation was a crisis, a revolutionary one, with a bloody climax, forecasting the Glorious Revolution, the French Revolution, and the Bolshevik Revolution, in the Thirty Years War.

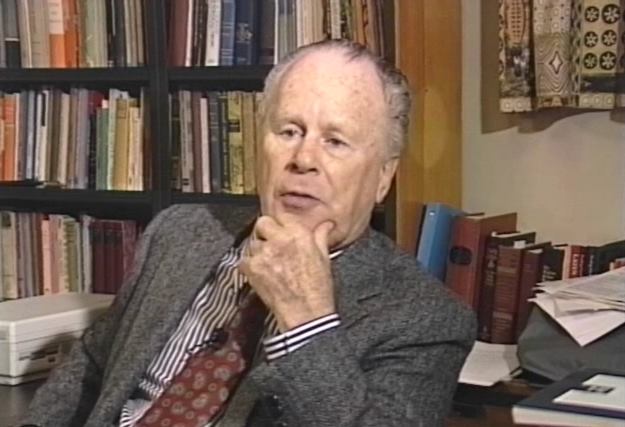

Charles Pierre Baudelaire (1829 – 1867)

Modern people being historyless naturally know nothing of the Thirty Years War, at the beginning of which there were twelve million people in the German-speaking northern part of Europe and at the end six million or five or four depending on the count. Modern people have heard of World War Two, which they reduce to two place-names, but they have only the vaguest idea of World War One, which was really only the first phase of World War Two. Modern people think that the Twentieth Century was the real Century of Progress, the span of time in which modernity became really modern at long last, and whose “Progressive” triumph they are the ones destined to complete. A more realistic assessment of the Twentieth Century would be that it saw the definitive breakdown of Western Civilization in wars and revolutions that killed as many people proportionate to the population as did the Thirty Years’ War – and that moreover those revolutions and wars were a religious phenomenon. The Protestants of the Reformation believed that they could build a more perfect society by purging every last influence of the Apostolic Succession. Instead, they plunged Christendom into a three-decades-long fugue of horrific violence. Enlightened Eighteenth-Century revolutionaries believed that they could build a more perfect society by purging, not only the divine kingship, but every vestige of superstition, whether Catholic or Protestant, as they, not noticing their own fierce religiosity, called religion. Instead, they plunged La belle nation into a perpetual crisis from which to this day it has not recovered; and they plunged Europe, by the paroxysm of the Napoleonic wars, in the course of which the general raised whole armies and threw them away, into the adventure of competitive imperialism that would issue in the declarations of August 1914. Imperialism managed to export some violence, but the Nineteenth Century was hardly a peaceful century on the Continent: Prussia swallowed up most of Denmark, turned on Austria, and then again on France; Italy suffered itself to be unified in Garibaldi’s Napoleonic campaigns; and the USA bled itself in the War of Southern Secession, after which it started a war with Spain and made itself an empire in the Caribbean and the Pacific.

August 1914 birthed October 1917, which swiftly birthed November 1917, which, by a reaction, birthed March 1933. Modernity is a fugue of ultra-Wagnerian length with many stretti, which has yet to reach its coda, and which we are all foredoomed to live through whether we subscribe to it or not. The Great Puritanical Regime of Homo Economicus killed tens of millions in Russia and as many as a hundred million in China. Under the banners of Globalism and Multiculturalism, that regime is initiating a new campaign of belligerent activism; it has migrated to a new territory, North America, where the underlying Puritan stratum, characteristically prone to witch-hunting and always delighting in moral police-work, receives it gleefully and imagines that it can write the final chapter of the Book of Progressive Revelations. Indeed, in a signal name-change, Liberalism, which was long synonymous with Modernity, now calls itself Progressivism, even claiming to be “post-modern,” but it represents Progress only insofar as the Salem Witch-Trials represented Progress, which they did not, the only real Progress being defined by an increase in the degree in which conscience, as opposed to doctrine, may express itself. Au contraire: The Witch-Trials, like all attempts to surpass the horizon of the Pagan-Jewish-Christian mélange calling itself (not inappropriately) Catholicism, only fell back into the hoariest of pre-philosophical, pre-moral rituals.

José Ortega y Gasset (1883 – 1955)

Oh! – And Europe’s Utopian, that is, Progressive, regime is so intent on fulfilling the Revolutionary imperative of abolishing every trace of history and convention that it is fanatically busy submerging its autochthons in a deluge of cultureless, historyless, lawless savages, mostly male, ages seventeen to twenty-five who, to the extent that they adhere wittingly to anything whatever apart from the basest of appetites, adhere to a worldwide sacrificial cult whose record-book, now fourteen centuries old, is nothing less than the ceaseless extinction of kingdoms, principalities, and peoples – and the sexual enslavement of their women. To criticize the blandly-named European Community’s immigration policy and increasingly merely to criticize Islam invites censure and punitive action, aggressively in Europe and with growing Puritan ardor in North America. Indeed the trappings of the cultureless, historyless, anti-spiritual Puritan Police State are in evidence everywhere. The regime permits the term “politically correct” only because “politically correct” is a euphemism for the police state. The regime is a police state but does not wish to be called one.

A sonnet, mellifluous if a touch obscure, from 1838 suggests the situation of the actually conscious individual of the West in 2015:1

La Nature est un temple où de vivants piliers

Laissent parfois sortir de confuses paroles;

L’homme y passe à travers des forêts de symboles

Qui l’observent avec des regards familiers.

Comme de longs échos qui de loin se confondent

Dans une ténébreuse et profonde unité,

Vaste comme la nuit et comme la clarté,

Les parfums, les couleurs et les sons se répondent.

II est des parfums frais comme des chairs d’enfants,

Doux comme les hautbois, verts comme les prairies,

— Et d’autres, corrompus, riches et triomphants,

Ayant l’expansion des choses infinies,

Comme l’ambre, le musc, le benjoin et l’encens,

Qui chantent les transports de l’esprit et des sens.

III

The Riffs

The poet, in case anyone needs to be told, is Charles Baudelaire (1821 – 1867), the founder of the Symbolist movement, a Bohemian, a relentless and incisive critic of Modernity, and by his own quite plausible claim the successor to the greatest of all critics of Revolution, Joseph de Maistre (1753 – 1821). Considering the coincidence of the natal and the mortal dates, it is perhaps a case of Pythagorean metempsychosis. In graduate school at the University of California Los Angeles in the mid-1980s a lady professor of comparative literature indicated in a lecture that she thought Baudelaire was a Liberal, a Revolutionary, and a supremely rational anti-Christian because… well because what else could he be but the mirror-image of her? It goes to show the degree to which perceptually, as well as cognitively, the professors have been impaired for decades. Baudelaire was the opposite of all those things that the lady comparative literature professor thought he was. Under the Second Empire, while scorning Economy to live as a poet and art-critic, Baudelaire unfolded in verse and prose his ethnography of Modernity as the resurgence, in la foule, “the crowd,” or what José Ortega would later call the masses,2 of the Dionysiac. Well should a wise man remark that this insight, which Baudelaire owed to de Maistre, puts him in the opposite camp from Friedrich Nietzsche, whose hatred of Christianity led him to extol the Dionysiac. In one of his notebooks Baudelaire, accessing a vision of the future, wrote: “The time will come when humanity, like an avenging ogre, will tear the last morsel from those who believe themselves to be the legitimate heirs of revolution. And even that will not be the worst.”3 The morsel will be all that is left, as in Europe, once Jean Raspail’s scenario has worked its way to its inevitable end; or in the USA once the social-justice warriors have redistributed everything.

Joseph-Marie, Comte de Maistre (1753 – 1821)

Baudelaire’s sonnet, “Correspondences,” is fugal. It describes the perpetual crisis of the West since the Reformation, the slow war of attrition against Christendom and even against the Philosophical Paganism that inserted itself at the core of Christendom. The keynote is confusion, as in Baudelaire’s line concerning the “confused words” uttered by the “living pillars” of Nature’s temple. The image conjures up the vaults of a Gothic cathedral – indeed, the Gothic arch is said to have come from the archaic custom of tying saplings at the top to make an altar in the forest. The parishioners of this particular temple have, however, forgotten its function: Their utterances resemble the stretto of the fugue, in which the theme has undergone the sparagmos, leaving only the disjecta membra, which the orgiasts toss about in a gruesome, meaningless subversion of the Eucharist. It is not the Progressive Regime’s propositional and pliable man who “passes through” the forest; it is, rather, “the man,” the unadjusted, pre-modern individual. The upright Pillars of the Community – good Liberals – suspiciously eye any individuated self; they “observe him with familiar glances.” It is the surveillance regime of the maternal state, spotting a dissenter instinctively. What happens to “the man”? He disappears from the poem after the first quatrain, as though something drastic had occurred. The second quatrain suggests a primeval Kultopfer. The confounding of the “distant echoes” again bespeaks a performance that rehearses a crisis and that is, itself, a crisis – a “dark unity.” The phrase “community organizing” springs to mind.

Considering that their game is a zero-sum game, what do the Globalizing community organizers get from their Kultopfer? They get the triumph of their corruption – the sensations of infinite justification and infinite righteousness in the destruction of the unadjusted man. They experience religious transport. It is even better when in Big-Brother fashion the community organizers induce the victim to endorse his own indictment. Baudelaire writes in a notebook entry: “That the sacrifice may be perfect there should be joy and consent on the part of the victim.”

IV

A Definition of a Conservative

A historyless, cultureless person who believes that life today is normal, and that things have always been normal; and who judges that Globalization must be good for people because it is merely an improvement on what is normal – that is, the subjection of everything to Economy. A Traditionalist, by contrast, grasps Globalization as the exportation of crisis not only to every quarter of the world, but to every city, town, and village of every niche of every quarter of the world. A Traditionalist grasps that Progress is deeply abnormal, globally existential in its implications, and that its crisis-mongers cannot be bought off. The price of stopping them is much higher than any simple bribery – and there is no room for hedging.

– Thomas F. Bertonneau is an American intellectual and professor. He has taught at a variety of institutions, and has been a member of the English Faculty at State University of New York, Oswego, since 2001. His articles and essays have appeared in a diverse array of scholarly journals including William Carlos Williams Review, Wallace Stevens Journal, Studies in American Jewish Literature, North Dakota Quarterly, Michigan Academician, Paroles Gelées: UCLA French Studies, and Profils Americains. He was a major contributor to the English section of The Brussels Journal. More recently, his work has appeared in The University Bookman, the John William Pope Center for Higher Education Policy as well as the websites The People of Shambhala and The Orthosphere.

– Thomas F. Bertonneau is an American intellectual and professor. He has taught at a variety of institutions, and has been a member of the English Faculty at State University of New York, Oswego, since 2001. His articles and essays have appeared in a diverse array of scholarly journals including William Carlos Williams Review, Wallace Stevens Journal, Studies in American Jewish Literature, North Dakota Quarterly, Michigan Academician, Paroles Gelées: UCLA French Studies, and Profils Americains. He was a major contributor to the English section of The Brussels Journal. More recently, his work has appeared in The University Bookman, the John William Pope Center for Higher Education Policy as well as the websites The People of Shambhala and The Orthosphere.

Endnotes:

- The editions of Baudelaire are innumerable; the poem, called “Correspondences,” enjoys much iteration on the Internet.

- See generally: José Ortega y Gasset, The Revolt of the Masses Anonymous (trans.) (New York: Norton, 1993 [1930]).

- Charles Baudelaire, Intimate Journals Christopher Isherwood (trans.) (New York: Howard Fertig, 1977 [1930]) p. 56.

Citation Style:

This article is to be cited according to the following convention:

Thomas F. Bertonneau, “Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs on Baudelairean Traditionalism” SydneyTrads – Weblog of the Sydney Traditionalist Forum (17 October 2015) <sydneytrads.com/2015/10/17/2015-symposium-thomas-f-bertonneau> (accessed [date]).

Leave a comment