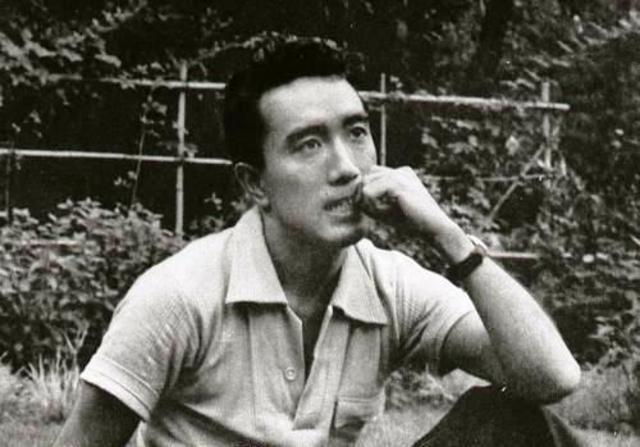

The BBC obituary for Venner begins with the following sentence: “Dominique Venner, the far-right French essayist who shot himself before the altar of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris on Tuesday, was a bitter opponent of same-sex marriage and influence of Islam in France.”1 David Sessions, the obituarist for The Daily Beast, after noting its subject’s transformation from active insurrectionist to contemplative historian, writes: “Venner and the Nouvelle Droite never for a second veered from their racialized supremacism. Not only is it present in Venner’s writings but even in his final blog post, in which he cited The Camp of the Saints, a fictional screed about the obliteration of Western culture by immigrants authored by the racist ideologue (and fellow Académie Française prize winner) Jean Raspail.”2 The New Yorker obituary attests that, in his suicide-note, Venner “singled out Muslims – he was an unapologetic Islamophobe – but… also evoked the racist, xenophobic, and anti-Semitic rhetoric of the Fascist European right between the two World Wars, which has been moderated, though not abolished, by postwar hate-speech laws.”3 Judith Thurman, the New Yorker obituary writer, finishes up by noting Venner’s admiration for Yukio Mishima, adding this: “It is, perhaps, apt to note in this context that Mishima’s works are rife with homoerotic imagery and sadomasochism, that he was known to frequent the gay bars of Tokyo, and that his early novel ‘Confessions of a Mask’ tells the story of an anguished, alienated teen-age boy, coming of age in repressed postwar Japan, who discovers that he is gay.”4 As Venner writes in the Histoire: “The thought police meanwhile never cease to hunt down Evil, that is to say, the fact of being different, being individuated, loving life, nature, the past, cultivating critical thinking and refusing to sacrifice to the universal deity.”5

Yukio Mishima (b. 1925 d. 1970)

What would happen if the critic, momentarily adopting the spirit of the times, submitted the three sample obituaries to the Left’s much-touted deconstructive procedure? The critic would begin by noting that the regime, lacking the wordbook of objectivity, can discuss nothing except in the Manichaean dichotomies of its socialist rhetoric. Thus for the BBC writer, Venner was “far-right,” the oppository to term his own far-left conviction, which, of course, he does not need to mention, as his readers share and assume it. For the BBC writer, no opponent of homosexual marriage or Islamic immigration can be anything other than “bitter.” (Recall Barack Obama’s characterization of Southern Christians as bitter clingers.) Nor apparently is immigration an allowable term: Islam’s presence in Europe must be reduced to the rhetorically neutral term influence, as though the hundreds – or is it now thousands – of victims of Muslim sexual mayhem and murderousness in France, Germany, and Sweden had encountered nothing more than the benignity of classical oratorical persuasion. Again for the Daily Beast writer, in discussing dissentient views, there may be nothing except pejorative hyperbole. For him, to defend Europeans and European civilization, to suggest that there should be limits on immigration, or perhaps a ban, is to engage in “racial supremacism,” while the creedal super-bigotry of Islam scuffles away out of sight.

The New Yorker’s Thurman serves up a particularly rich effluvium of hypocritical vituperation. For hypocrisy, take her phrase to single out. Venner, like others of his ilk, tirelessly admonished a misled public that Islam is not a religion like any other, but an extraordinarily peculiar and savage doctrine that singles out everyone who is not a Muslim – and singles him out for persecution and murder. If the scapegoating formula to single out were to be employed properly, it would necessarily be applied to Islam, not to the critics thereof. Yet it is Venner, in Thurman’s diction, who qualifies as “an unapologetic Islamophobe,” that final term serving like racist or sexist to mean anyone with whom the writer disagrees. Unsurprisingly, the word racist is next up in the verbal order. Thurman would have her readers believe that “postwar hate-speech laws,” a phenomenon of the last two decades, ended Fascist rhetoric; when in fact it was Allied blood and treasure in World War Two, culminating in the revelation of the death camps, which made such rhetoric shameful – except in Islam. Thurman now executes her nastiest whopper of all by implying that Venner felt attracted to homosexuality and sadomasochism. The gesture is remarkable for its blatant self-exception from liberal principles. For the good liberal, there is nothing wrong with homosexuality – in fact, it is a positive good – whereas sadomasochism is merely a private matter. In the case of Venner, however, these two sacred things constitute a tar-bucket of moral condemnation that Thurman may apply as thickly she likes.

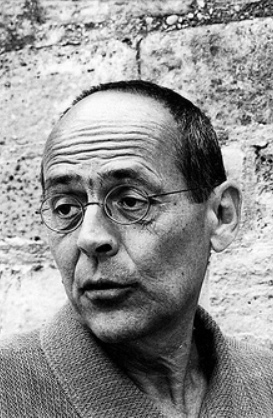

Louis Althusser (b. 1918 d. 1990)

Consider the obituaries that ensued on the death of the philosopher Louis Althusser in 1992. Althusser was a lifetime Communist who, after murdering his wife in 1981, served a lenient prison sentence that lasted a mere three years. The New York Times obituary only mentions the murder in its fourth paragraph of thirteen.6 The laconic first paragraph reports the bare fact that “Louis Althusser, a French Communist philosopher who was a prominent critic of French and Soviet Communism in the 1970’s, died Monday of heart failure in a geriatric center outside Paris.” The second paragraph, equally bland, tells how “Mr. Althusser had taught for many years at the prestigious Ecole Normale Superieure in Paris and was himself one of its graduates.” Eric Pace, Althusser’s obituarist in The New York Times uses no terms that would equate to those used insultingly by the obituarists of Venner; there is in his prose almost no editorial language, unless the blandness itself is taken as editorial, which perhaps it is. Reviewing an English translation of Althusser’s posthumous memoir, Alice Kaplan for the Los Angeles Times sought to mitigate the homicide: “Those who knew Althusser understood that whatever fit of madness induced him to strangle Helene was not brought on by the world of politics.”7 The reviewer then represented Althusser as an “elegant theorist… who redefined the concept of ‘ideology’ as ‘our imaginary relationship to real conditions of existence.’” As late as 2009, Etienne Balibar in The New Left Review could refer to Althusser as “the unfortunate and scandalous protagonist of an unexpected fait divers, the murder of his wife Hélène, within the very walls of the École Normale.”8 Far from being bland, the sentence is suavely exculpatory.

A current darling of the Parisian Left, Bernard Stiegler, often described by his apologists as the successor both of Martin Heidegger and Jacques Derrida, spent his twenties as a Leftwing extremist whose gang robbed banks at gunpoint. Stiegler served a prison term for his crimes from 1978 to 1983, three years longer than Venner’s incarceration. Try to find any details of Stiegler’s crimes on the Web. Vigilant parties have scrubbed the references. The Wikipedia tells only that Stiegler served time for armed robbery. One can, however, access Stiegler’s discussion of the crime of Patricia and Emmanuel Cartier entitled The Disaffected Individual in the Process of Psychic and Collective Disindividuation, which figures as the third chapter of his book Les sociétés incontrôlables d’individus désaffectés.9 In 2005, the Cartiers, facing mounting debts, decided to kill their four children and then commit suicide. They chose for the method of homicide insulin injection. The couple managed to kill only one child, a girl, Alicia. The suicides failed. A criminal court sentenced the killers to ten or fifteen years behind bars, depending on their behavior. Stiegler poses a rhetorical question, “Does this mean that these parents no longer loved their children,” to which he answers, “Nothing is less sure.” The phrase does not complete the sentence, which carries on for something like seventy words.

Bernard Stiegler (b. 1952)

The upshot is: Society made them do it so that society is just as culpable as they. In a subsequent paragraph, Stiegler claims that “the Cartiers… are as much victims as perpetrators.” Stiegler’s words are, of course, fatuous, but they are also a hoary cliché. Part of the scandal of Stiegler, as of other contemporary academician-writers, is his and their purveyance of ideas that were already hackneyed in 1848 as though they were brilliant new insights. But it takes two to tango. The university-trained readership that consumes postmodern prose is equally culpable with the producers of it.

In The Shock of History, LeComte asks Venner why philosophers and intellectuals “become rabid defenders of lying, chimeric, and backwards systems.”10 Venner responds that the tendency arises from peculiarities of the European mentality, which gravitates to ever higher levels of abstraction. The abstractions acquire the rigidity of absolutes, for which “in heated collective and historical situations, men have killed and died.”11 More generally, the tendency arises from human nature. Beyond the physical necessities, people require meaning, which they can only find in the available symbols. The reigning modernity, long in the making, has censoriously diminished the repertory of symbols and has thereby created a crisis of meaning, among the results of which are the ugliness of the public square and the suicidal incoherency of policy, as for example in the domain of immigration. Where an impoverishment of meaning prevails, hysteria and extremism will constitute natural responses. Venner makes an historical comparison: “While the European everyman of the thirteenth century, lord or shepherd, was satisfied with a rudimentary belief in a tutelary God, the clergy’s very existence was driven by theological reflection. The same is true of the secular theologians we have today in the form of political scholars.”12

According to Venner, “the intellectual is imbued to his core by the certainty that concepts are the only true facts, and that he is their enlightened interpreter, while the commoner, as in Plato’s allegory of the cave, can only discern the half-deformed shadows they cast.”13 The observation puts Venner in much good company. He comes parallel, for example, with Eric Voegelin’s notion of ideology as a second reality, or again with Voegelin’s contention that the modern political scene is essentially Gnostic. When Venner ascribes to the contemporary intellectual class its being intoxicated by rigid abstraction, he might as well be invoking Gnosticism. Cognoscenti of Voegelin might protest that, contrary to Venner, Voegelin discovers in Christianity an increase in the differentiation of symbols over Paganism hence also a clarification of the human predicament. Voegelin’s students would for this reason prefer his diagnosis of modernity to Venner’s because of Venner’s failure to grasp the subtleties of Christian revelation. Voegelin might be closer to Venner, however, than his partisans would think. In the fourth volume of Order and History – The Ecumenic Age (1965) – Voegelin makes a statement that a good many of his readers fail to remark. The context is Voegelin’s history of Christian symbolism from Paul to the Council of Nicaea; what impresses and pleases Voegelin in these earliest centuries of the faith, is the plasticity and plurality of its symbolism and the closeness of that symbolism to the experience of transcendence. Voegelin’s phrase for describing the phenomenon is “the openness of the theophanic field.”14

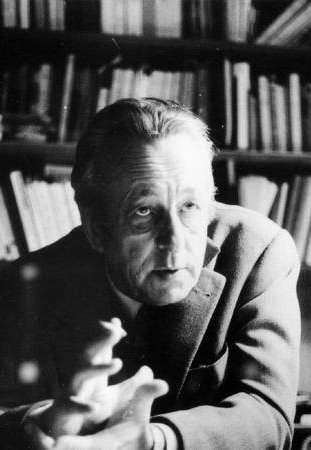

Eric Voegelin (b. 1901 d. 1985)

Voegelin goes on to say that, “The openness of the theophanic field, though it came under pressure when the Church felt it necessary to distinguish its ‘monotheism’ from the ‘polytheism’ of the pagans, could be substantially preserved for almost three centuries.”15 Voegelin admires Origen, anathematized by the later clergy, for the poetic fluidity of his symbols, some of which, like the symbol of fire, show conscious continuity with the origins of philosophy, as in Heraclitus, with his fire and lightning. “Up to Nicaea (325),” Voegelin writes, “when the Athanasian victory put an end to this generous openness, Christianity was substantially ditheistic.”16 Elsewhere, Voegelin writes apologetically about Late-Pagan Summodeism, which approximates Christianity so closely in his view that only the doctrine-obsessed clerical mind at its most rigid could invidiously distinguish one from the other. In comparison with Venner, Voegelin must appear the more generous soul because Voegelin’s embrace reaches farther than Venner’s, finding commonality where Venner finds irreconcilable enmity. However, Voegelin’s approval of Early Christianity implies his criticism of Post-Nicene Christianity, which is not so different from Venner’s when he deplores the Old-Testament zeal of the Alexandrian bishops or the medieval heresy-hunters.

Just as Venner exhibits affinities with Voegelin, he exhibits them again with Father Seraphim Rose (1934 – 1982), the American Greek-Orthodox diagnostician of modernity. Venner’s critique of nihilism runs strongly in parallel with Father Rose’s, as set forth in the latter’s little volume, Nihilism: The Root of the Revolution of the Modern Age (1994).17 Passages from Venner could be inserted into a chapter by Rose and no one would notice; and ditto the other way around. Both men are apt, for example, to quote Nietzsche with approval. Here is Venner on nihilism:

Jünger has suggested that, to represent nihilism, it is less necessary to picture bomb-throwers or youthful activist-readers of Nietzsche than it is to picture ice-hearted high functionaries, either academicians or financiers, in the exercise of their offices. Nihilism is in effect nothing other than the mental universe required by their calling, that of rationality and efficiency as supreme values. In the best cases, [nihilism] manifests itself by the will to power, and, more often, by the most sordid of trivialities. In the world of nihilism, everything is subject to utility and desire, in other words, to that which is qualitatively inferior.18

Venner continues with a long additive iteration: “It [nihilism] is the world of applied materialism, of nature transformed into garbage, of love travestied as sexual consummation, of the mysteries of the personality explained by the libido, and those of society elucidated by the class struggle, of education tuned into a factory of specialists, of the morbid glut of information substituted for knowledge, of a backwards politics made subordinate to the economy, of happiness brought down to the level of mass tourism, and, when things turn bad, the slide into violence without brakes.”19 And here is Rose on nihilism:

Nihilist “organization” – the total transformation of the earth and society by machines, modern architecture and design, and the inhuman philosophy of “human engineering” that accompanies them – is a consequence of the unqualified acceptance of industrialism and technology which… must end in tyranny. In it we may see… the transformation of truth into power. What may seem “harmless” in philosophical pragmatism and skepticism becomes something else again in the “planners” of our own day. For if there is no truth, power knows no limit save that imposed by the medium in which it functions, or by a stronger power opposed to it.20

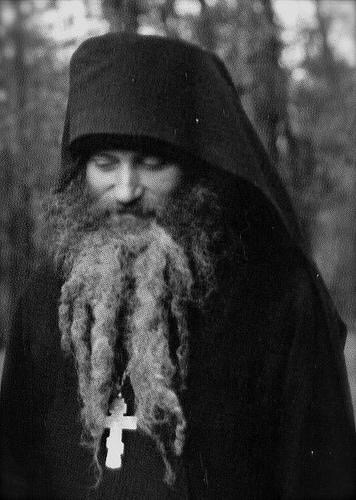

Fr. Seraphim Rose (b. 1934 d. 1982)

Venner’s “specialists” and “functionaries” are Rose’s “planners.” Where Rose refers to revelation, in which, as he sees it, human dignity stands rooted, Venner refers to tradition; but, formally, both terms make reference to something transcendent whose validity the modern order petulantly and ceaselessly calumniates. Rose is an Orthodox Christian and Venner some kind of synthetic Pagan who experiences a Wordsworth-like nostalgia for les divinités sylvestres, but each incorporates a theological strand in his critique of modernity unleashed. Rose and Venner thus differentiate themselves equally from the liberal-totalitarian order, which while religiose, remains nevertheless vehemently anti-theological and nihilistic. There is no reason why Venner should have been aware of Rose (nor vice versa), but remarking the convergence of their respective critiques calls attention once again to the limitation in Venner’s thinking to which Part I of this essay addressed itself. If Venner were not aware of Rose (once again – why should he be?), he would have been more than aware of the specifically Right-Catholic critique of modernity beginning with Joseph de Maistre (1753 – 1821) and embracing such dissimilar writer-personalities as François-René de Chateaubriand (1768 – 1848) and Charles Baudelaire (1821 – 1867) that is undeniably ancestral to his own. Venner’s intellectual closeness to those precursors ought to have suggested to him that his refusal to find some rapprochement with Christianity was shakily founded. The utter hostility of the Left to Christianity might have spoken to Venner in the same way.

On the other hand, when Venner writes, as he does in The Shock, of the corruption of the modern Christian churches, including Catholicism, it becomes difficult even for a Christian apologist to disagree with him. The Zombie-metamorphosis appears to have pervaded the Protestant denominations to the point where they are indistinguishable from liberal social clubs like Unitarianism or the YWCA. The most traditionally Anglican Anglicans nowadays are those who follow a breakaway African branch of the sect headed by bishops from Uganda and Tanzania. The Catholic Church in Europe, meanwhile, has abdicated any defense of its own creed and history, as its leadership all the way up to the sitting Pope turns a perversely blind eye to the Islamification of the continent and the inevitable ensuing annihilation of what remains of Christendom. What, among the vestiges of the cultural inheritance of Europe remains untouched by the blighting pox of nihilism? Only the incontaminable sources remain – which is why Venner turns to them so hopefully despite his desperation. Of Homer, Venner writes, “He is the very source itself”; according to Venner, Homer “addresses the massive confusion into which Europe has been thrown.”21 The heroic action in Homer’s poems, their clarity of worldview and perspicuous realism, even where it concerns the gods, stand in the strongest possible positive contrast to the insipidity and jejuneness of feminized liberalism. The primitive matriarchy currently enjoys resurgence in the dominion of the de-sexed and self-righteous crone – and her reign is the same sacre du printemps as in hoary, Pre-Indo-European antiquity.

Joseph de Maistre (b. 1753 d. 1821)

“Nothing,” writes Venner, “save perhaps a crude nihilism, can support the appetites of pleasure-seekers and predators who cloak themselves in moralizing discourse.”22 Even in the cases of religion and philosophy, which, in the modern context are corrupt, Homer offers a purifying vision. Whereas under political correctness, that new manifestation of Puritanism, the state demands compliance with a model of guiltless moral perfection; in Homer, by contrast, the exemplary persons are far from perfect. On the contrary, “their vitality,” which for Venner is a virtue, “is counterweighted by their subjection to error and immoderation, and they pay a price for it.”23 Given that political correctness operates through the pseudo-Christian inculcation of measureless guilt, Venner’s claim that the value of the Pagan vision consists in its liberation of men “from the overwhelming guilt so often imposed on them by other systems”24 acquires plausibility. Venner also finds in the Iliad and the Odyssey the wisdom that “vanity, envy, anger, stupidity, and other defects incite calamity.”25 In fostering just such anti-values, the liberal-totalitarian regime is inciting calamity.

Wise people who defer worshipfully to the Three-in-One, who see the danger in the creed that defers sacrificially to a bloodthirsty one, and again see a danger in those whose deity is the morbidly insipid none, or rather the sacrificial nothing, and who abet those who worship the one and persecute and murder in its name, because, ultimately, the none and the one are the intolerant same: Those wise people, I say, might want to accept an ally in someone who defers worshipfully, if a bit Quixotically, to the Olympian Dozen or even to les divinités sylvestres.

Only Venner’s Shock currently exists in English. That is a pity. The Histoire should be translated into English and published on an emergency basis. Venner’s Blancs et les Rouges, his account of the Russian Civil War, would also likely find an audience, and be extremely useful, in an English language edition. Un samouraï de l’Occident is richer than The Shock of History. It too should be translated in full. Those who can read, or even only struggle with French, might want to tackle the Histoire, which Venner wrote in his usual quite ordinary language. The effort would be more than rewarded.

[Return to Part I]

Prof. Thomas Bertonneau

– Thomas F. Bertonneau is an American intellectual and professor. He has taught at a variety of institutions, and has been a member of the English Faculty at State University of New York, Oswego, since 2001. His articles and essays have appeared in a diverse array of scholarly journals including William Carlos Williams Review, Wallace Stevens Journal, Studies in American Jewish Literature, North Dakota Quarterly, Michigan Academician, Paroles Gelées: UCLA French Studies, and Profils Americains. He was a major contributor to the English section of The Brussels Journal. More recently, his work has appeared in The University Bookman, the John William Pope Center for Higher Education Policy as well as the websites The People of Shambhala and The Orthosphere. He has also contributed to the Symposia of the Sydney traditionalist Forum.

Endnotes:

- “Obituary: Dominique Venner” BBC (online) (21 May 2013) <bbc.com> (accessed 30 October 2016).

- David Sessions, “The Fascist History Behind Dominique Venner’s Suicide at Notre Dame” The Daily Beast (online) (23 May 2013 @ 6:45 PM ET) <thedailybeast.com> (accessed 30 October 2016).

- Judith Thurman, “Dominique Venner’s Final Solution” The New Yorker (online) (22 May 2013) <newyorker.com> (accessed 30 October 2016).

- Ibid.

- Dominique Venner, Histoire et Tradition des Européens: 30,000 ans d’identité (Monaco: Editions du Rocher, 2011) p. 221. The writer’s translation, as hereafter, with assistance from “Tiberge”.

- Eric Pace, “Louis Althusser, 72, a Marxist Who Harshly Criticized Moscow” The New York Times (online) (24 October 1990) <nytimes.com> (accessed 30 October 2016).

- Alice Kaplan, “A Living Death : The Future Lasts Forever: A Memoir, By Louis Althusser . Translated by Richard Veasey . Introduction by Douglas Johnson; Editors’ foreword by Olivier Corpet and Yann Moulier Boutang (The New Press: $25; 365 pp.)” Los Angeles Times (online) (13 March 1994) <latimes.com> (accessed 30 October 2016).

- Etienne Balibar, “Althusser and the Rue D’Ulm” New Left Review No. 58 (July-August 2009) (online) <newleftreview.org> (accessed 30 October 2016).

- Bernard Stiegler, Mécréance et Discrédit 2: Les sociétés incontrôlables d’individus désaffectés (Édition Galilée, 2006). For English: “The Disaffected Individual in the Process of Psychic and Collective Disindividuation” Patrick Crogan and Daniel Ross (trans.) Ars Industrialis (online) (19 August 2006) <arsindustrialis.org> (accessed 30 October 2016).

- Dominique Venner, The Shock of History: Religion, Memory, Identity, Charlie Wilson (trans.) (London: Arktos, 2015) p. 92.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. p. 93.

- Ibid.

- Eric Voegelin, The Ecumenic Age (Louisiana State University Press, 1965) p. 259.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Eugene Rose (Father Seraphim), Nihilism: The Root of the Revolution of the Modern Age (Herman Press, 2009 [1994]).

- Dominique Venner, Histoire et Tradition des Européens: 30,000 ans d’identité, op. cit., p. 18.

- Ibid.

- Eugene Rose, Nihilism: The Root of the Revolution of the Modern Age, op. cit., p. 79.

- Dominique Venner, The Shock of History: Religion, Memory, Identity, op. cit., p. 102.

- Ibid. p. 102.

- Ibid. p. 105.

- Ibid. p. 106.

- Ibid.

Leave a comment