A View of the Political Scene

The election of Donald Trump and the decisive ways in which he has acted against the immigration lobby and other entrenched leftist interests since his inauguration on January 20 have led to noisy protests throughout the Western world. These have come not just from the usual suspects on the political and cultural left, but the nominal “establishmentarian” right has also joined the chorus of castigation. Indeed it is almost impossible to compare Trump to any recent Republican presidency. As mentioned in the Sydney Traditionalist Forum’s recent “Yearly Review”, Trump has exposed an acute identity crisis that has facilitated an electoral paradigm shift among many once-conservatives, many of whom are starting to finally break out of the shackles of tribal electoral politics:

What those who pose as our political betters do not (and show no sign of being able to) understand is that it is precisely Trump’s lack of “conservatism” that may rescue those things that soi-dissant anti-leftists profess to revere but have failed utterly in preserving over the last several decades […] Thank heavens Trump doesn’t have the “character and tenacity” of the usual suspects! Ironically, it may be this non-conservative populist in the US, with his finger on the pulse of what our [PM Robert Gordon] Menzies once called the “forgotten people” who may more competently achieve what these “conservatives” were evidently inept at securing themselves.¹

Trump certainly appears to have struck a chord, within and beyond his native America. Nonetheless, I would ask the reader to bear in mind that I wrote as an American, not Australian, observer and as someone who followed Trump’s campaign from beginning to end. My wife and I also stayed up bleary-eyed on Election Night until Trump’s obnoxious feminist opponent received her comeuppance; and we cheered with all the others whom Hillary relegated to her “basket of deplorables” when our state of Pennsylvania put The Donald over the top.

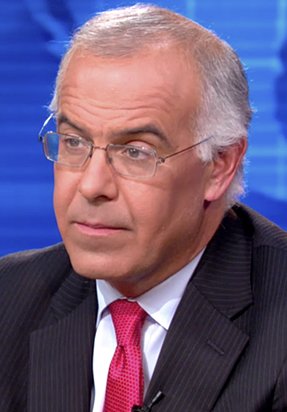

![]()

David Brooks

Among the most intriguing ambiguities in the victorious candidacy of President Trump was its subverting the narrative of mainstream “conservatism” by running against establishment Republican candidates. This complaint reveals hypocrisy of a magnitude rarely encountered in human affairs. This is illustrated by David Brooks, the resident “conservative” columnist at the New York Times, genuflecting before the most recent failed Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney for denouncing Trump as a threat to “conservatism.”2 Brooks’s charge and his defense of Romney as the rightful, true conservative enemy of Trump are ludicrous in more than one way. First, Brooks has been a gushing admirer of President Obama,3 and his claim to speak for the Right outside the editorial room of the New York Times is at the very least suspect. Second, Romney fawned shamelessly over Trump while running for president in 2012, and there is little in his recent declamations that was not contradicted by his obsequiousness when he was courting Trump as a backer.

In a particularly biting commentary, Richard Goodwin of the New York Post stresses Romney’s chutzpah in assaulting the current presidential front-runner. This, according to Goodwin, is coming from someone who in 2012 ran one of the most lackluster presidential campaigns in recent history.4 Although there is much that is flawed about Trump, it is ridiculous to imagine the Republicans could win the presidency with a “failed retread” who is trying to remain part of the political scene. There is nothing that qualifies Romney to be a spokesman for any Right, except for large corporations. He ran his presidential campaign from the center and moved gingerly toward the center Left on social issues after he gained the nomination, lest he be viewed as too extreme.

Despite his empty attributions, Brooks does cause us to reflect on the question: “What is conservatism?” As readers of my work and those who know my personal history would understand, this question has engaged me for decades, and the crusade against Trump – both during his Presidential campaign and continuing after his inauguration – has underscored once again the vacuous PR quality of the term in question. Why does Trump’s willingness to negotiate with President Putin, rather than engage him in a military confrontation, or to broker a peace between the Israelis and Palestinians, prove that he is not a “conservative?” That term has become so intertwined with Republican talking points or with efforts to give doctrinal gravity to certain party interests that it has lost any meaning outside of two recognizable groups: media figures trying to differentiate the two parties in elections and GOP loyalists and party workers seeking to give their partisan attachments some deeper metaphysical significance. Of all the charges leveled against Trump, the accusation that he is destroying “conservatism” may be among the most ridiculous. Actually he is challenging the hegemony of party bosses and exposing the decorative wrapping in which GOP elites have packaged their interests.

Jonathan Chait

A very unfriendly but also perceptive observer of Trump, Jonathan Chait, notes in New York5 what should be obvious but is not frequently mentioned. Trump is viewed as a wrecker by the Republican establishment and their neoconservative talking heads because he has dared to reverse certain priorities: “The Republican Party has for decades been organized around a stable hierarchy of priorities, the highest of which is to reduce taxes for the wealthiest Americans, i.e. ‘job creators,’ and loosen regulation of business. As long as their party is anchored by its economic consensus, conservatives tolerate wide disagreement on social issues.” Trump “proposes to invert the party hierarchy, prioritizing its right-wing social resentments while tolerating ambiguity on economics. And his popularity suggests that many average Republicans aren’t maniacally obsessed with shrinking the size of government.” Although one can challenge a number of Chait’s assumptions—for example, that reducing taxes for the wealthiest is the highest GOP priority (as opposed, for example, to being aggressively liberal internationalist in foreign affairs), that Republican politicians are “maniacally obsessed with shrinking government,” and that Republicans have made absolutely no efforts to attract minority voters—his presentation of the “threat” to the GOP establishment represented by Trump and his constituency is correct. Trump’s enemies in the party have noticed his inversion of the “party hierarchy” when he elevates social concerns that are found on the Right above the economic interests of the party’s donor class.

Finally, it should be pointed out that the Trump candidacy has underscored the problem of legitimacy in a society and polity that claim to be “democratic.” In American democracy, equality has become the highest value in terms of what politicians and political journalists invoke. This association is nothing new in the history of political thought. It goes at least as far back as Aristotle’s Politics, and the justification now given for the exercise of power by those who exercise it is that someone or other must give direction to our society, so that we can continue to move toward greater “equity,” “fairness,” or whatever other synonym is now made to stand for equality.

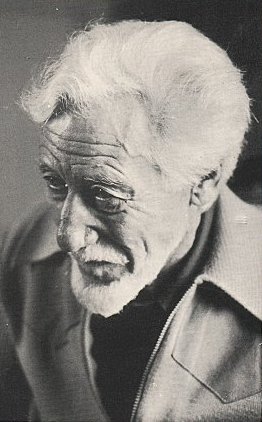

Bertrand de Jouvenel

Although other values may have purchase in modern democracy, such as freedom, social cohesion, and individual excellence, equality has a moral worth that exceeds that of other competing values. Note that this observation is not being extended backward to the founding of the American Republic or attributed to the authors of America’s original constitutional design. It is being applied to the way the United States and other Western-style “liberal democracies” have developed during the last hundred years or so, which is in the direction of embracing democratic equality as their highest political ideal. And this judgment is not gainsaid to whatever degree this ideal is not met. Political ideals are never perfectly realized in practice, and the fact that masses of people are mobilized for the purpose of achieving greater equality would suggest the staying power of equality as an ideal.

Even “democratic” freedom exists as an instrumental good that in a democracy is usually subordinated to equality. French political theorist Bertrand de Jouvenel argues in his classic On Power that equality progressively swallows up freedom in modern democracy, taking what had once been an aristocratic privilege and making it available to every individual through the state. Unlike medieval and early modern conceptions of “libertas,” which were vested in classes and corporations, the now regnant notions of freedom are bound up with a managerial state that guarantees an “equal right” to be free.

This leads to the vicious cycle that Jouvenel sums up in his oft-quoted aphorism: “Conceived as the foundation of liberty, modern democracy paves the way for tyranny. Born for the purpose of standing as a bulwark against Power, it ends by providing Power with the finest soil it has ever had in which to spread itself over the social field.”6 In democracy, economic privilege may continue to exist but is typically justified as leading to an increase in equality. For example, by allowing the poor to have more educational and vocational choices, Republicans assure us, we can close the socioeconomic gap. What benefits those in higher economic brackets, such as lowering marginal tax rates, will presumably open up more jobs to those who are at the bottom of the socio-economic heap and thereby lessen inequality. Like all measures intended to reduce taxes, this policy is defended on egalitarian grounds.

Carl Schmitt

Contrary to the view of a majority of public sector employees, racial minorities, feminists, and Democratic politicians, the demand for equality is by no means a strictly leftist thing. That demand is equally prevalent on the populist Right, which, as fate would have it, is now being energized. Why should we imagine that the gay activist in San Francisco demanding further rights for his group or the millennialist supporter of Bernie Sanders calling for more government-provided college tuition has the corner on egalitarian politics? Why can’t the blue-collar Evangelical in Alabama, who correctly sees his group as despised by present leftist elites while his economic prospects continue to fall, have an equally valid claim to democratic equality? Why is the latter being ignored when he observes that foreign labor forces are being imported to drive down his wages and that entire sectors of the economy have been sent to countries with low production costs? What deeply offends such claimants to equal treatment are elites who despise their moral and cultural beliefs while adding to their economic misery. Indeed, Third World immigration seems designed to promote the interests of these already hated elites, by replacing a native workforce with cheap labor (some of it illegal) and by creating the kind of cultural chaos in which the beliefs of those who are being marginalized will be diluted in an America they no longer recognize.

Carl Schmitt underlined as a problem of modern constitutional governments appealing to popular sovereignty an excessive dependence on legality.7 Such governments have to legitimate themselves by pointing to their legal foundation and to their use of fixed procedures in reaching decisions. But at times it becomes apparent that those who are stressing legality also possess the power and resources that allow them to determine what is legal for others. Thus it becomes clear that these elites are not simply the instruments of a fixed legal order but those who decide how others will live. The question then becomes whether these elites can legitimate their continued rule as bearers of something other than impersonal legality. Can they rule as representatives of the democratic will, that is, by advancing what is understood to be equality? An elite in a democracy that is not seen as committed to this goal puts itself in a precarious situation.

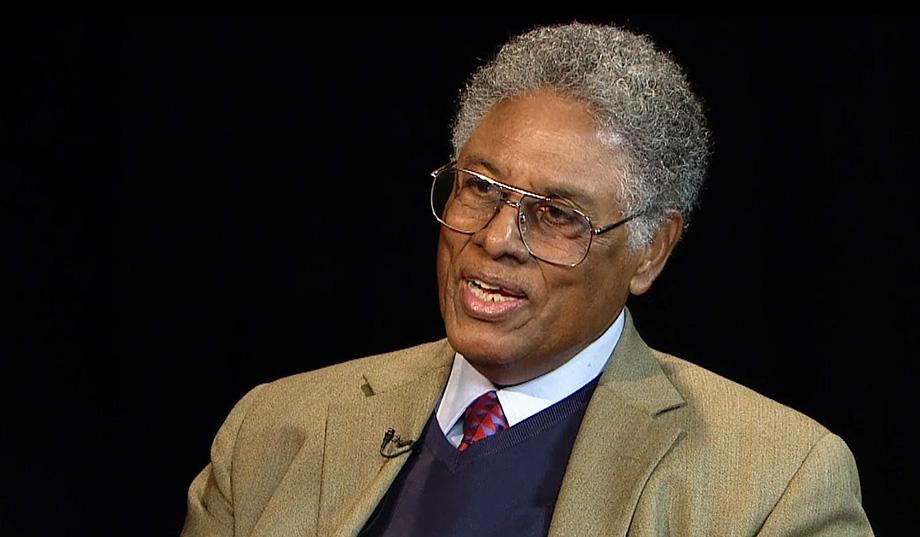

Kevin Williamson

Now those elites who identify with certain egalitarian interests, namely those of the social Left, can still make headway with the help of aggrieved minorities and general media and academic approval. Though Hillary Clinton’s candidacy was decidedly defeated after the college votes declared for Trump 304 to 227 on 19 December last year, her coalition seemed cohesive and mobilized during much of her Presidential campaign. Meanwhile, the spokespersons for the other claimants to equality, the ones who are classified as trailer-park trash and snake handlers, encountered heavy weather from the commentariate. Their claimants to equality are despised by the media and educational elites, and National Review editor Kevin Williamson has recently pounced on the white working class as the denizens of a fever swamp roiled by unjustified social resentments.8 This spurned demographic rallied to Trump because neither the social Left nor the spokespersons for the GOP donor base recognized its interests or democratic sensibilities.9 This demographic returned the favor by denying both the legality and legitimacy of those who scorn it.

Those who viewed the Trump movement as a right-wing phenomenon may have been correct, however hysterically or opportunistically they made this observation. A politically effective Right in the US will not likely come out of self-described cultural conservatives lavishing praise on the shining lights of the post-war conservative movement. Nor should one expect such a Right to emerge from Republican think tanks that are committed to liberal internationalism as a foreign policy and to the support of global capitalist donors. A Right that can push back with power against the Left must be able to harness the grievances of those who have been excluded by the ruling class and who offer a counter-ideology adapted to the present hour. Such a hypothetical or evolving Right might be expected to invoke an historical community and/or organic national ties against the advocates of globalization, fluid human identities and human rights rhetoric. French political thinker Arnaud Imatz views this pattern of thinking as coming out of a “non-conformist Right” in his own country, going back to nationalist revolutionaries in the interwar years, then progressing through the partisans of Charles de Gaulle defending French national sovereignty against American and Soviet imperialism, and finding more recent expression in breakaway French socialists who’ve rediscovered their loyalty to an historic French nation and a European identity.10

Arnaud Imatz

Imatz notes, as I do in The Strange Death of Marxism,11 that “the post-Marxist Left in France, even in its most radical form, does not oppose globalization. It claims to want to extend its economic benefits to the totality of the human race. It seeks to disseminate human rights all over the planet. This Left never call into question the global dogma of the interdependence of peoples and cultures and [like its American model] wishes to turn its land into a great melting pot, thereby ending any traditional association with a French nation. Far from disturbing what American elites call ‘democratic capitalism,’ the post-Marxist Left plays the role of the useful idiot that it had once mocked in French defenders of the American connection.”12 Imatz sees a single, unitary culture (la culture unique) taking the place of inherited European national cultures; and he maintains that economically, politically and culturally France and the rest of Western Europe have fallen under the influence of something specifically American and in its Atlanticist and “democratic capitalist” forms, nation-devouring.

Curiously what is condemned as an imported American ideology has generated a revolt in its homeland. The populist movement that has been centered on Donald Trump reflects most of the same forces that are associated with non-conformist thinkers and communitarian revolt in France (and presumably elsewhere in the world where reaction against the established political elites is gaining momentum, Australia included). Moreover, the reaction exhibited by representatives of our elites, whether Democrats, establishment Republicans, or neoconservative journalists, dovetail with those diatribes heard in Europe. Barack Obama’s comments in 2008 about “people who cling to their guns and religion”13 or Hillary Clinton’s mockery of a “basket of deplorables,”14 that is, those swarms of bigots who have rallied to Donald Trump, recall the attacks launched on the National Front’s constituency in France. And this need not surprise us. An establishment that battles for a liberal internationalist American foreign policy, governmentally-negotiated free trade agreements, and a globalist understanding of nationhood are reacting with concern to those who challenge its hegemony. Whatever one may think of these elites, they are justified in viewing those who are reacting against them as a danger of the first magnitude.

Paul Edward Gottfried, “The Strange Death of Marxism: The European Left in the New Millennium” (Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 2005)

Let’s also not think that if Trump turns out to be something less than what his followers (like my working-class neighbors in Central Pennsylvania) were hoping for, it would mark the end of their revolt against distant elites with anti-traditional values and alien economic interests. We may be witnessing what is only the beginning of a populist insurgency from a transformed, energized Right. Unlike the American conservative movement, this populist Right does not genuflect before the gods of capitalism. In fact it is not this Right but the social Left that is warming to a globalist economy run by a multinational capitalist class. It is the multicultural Left in the new political constellation that can make its peace with the immigration politics and “human rights” internationalism of, say, the Wall Street Journal or Commentary.

The real lines of division between Right and Left are between those who wish to preserve inherited communities and their sources of authority and those who wish to “reform” or abolish these arrangements. In the modern democratic world, one no longer encounters the entire package of an earlier Right, let alone that of classical conservatism.15 One no longer finds a viable ideology that combines a defense of particularity and organic relationships with a positive assessment of hierarchy. But the populist Right offers as much of an older Right as the present permits. It is among other things a response to the globalist Left and more specifically, to the custodians of Political Correctness, who view with increasing exasperation an unwanted populist insurgency. Spokesmen for the current populist Right would answer the question ”What is the principle of society?” less eloquently but no differently from a character in Benjamin Disraeli’s Tory democratic novel of 1845, Sybil. Disraeli’s mouthpiece in this controversial social novel “prefers association to gregariousness” and would never mistake “density of population” or mere human “contiguity” for a rooted community.16

Paul Edward Gottfried, “After Liberalism: Mass Democracy in the Managerial State” (New Baskerville: Princeton University Press, 1999)

Furthermore, when neoconservative apologists gild the lily for something called “democratic capitalism,” they no more than the populist Right have in mind returning to a pre-welfare state America. “Democratic capitalists,” as establishment Republicans and neoconservatives sometimes call themselves,17 accept most existing entitlement programs and are cautious about scaling back an expanding public administration. But they differ from the populist Right in this respect: they welcome a globalist economy, with all its disruptions, even if it causes unemployment and dislocation for the local working class. From the perspective of these optimists, things will work out for those who suffer deprivation in the short run. But for those who are uprooted from long settled homes in the American “Rust Belt” and forced to become nomads in search of work, the world looks different. Trump by addressing the demands of this constituency, has not moved the Republican Party to the Left. He is appealing to a socially conservative and preponderantly White segment of the population that the present ruling class and its media surrogates have not been especially interested in. In this, he is perhaps the most conspicuous symptom of a trend that will be felt throughout the Western democracies going into 2017.

– Paul Gottfried is Raffensperger Professor of Humanities Emeritus at Elizabethtown College (Elizabethtown, Pennsylvania, USA), the author of over a dozen books, plus numerous essays and book reviews, mostly dealing with political theory, modern European history and American political movements. His works are widely read and discussed in translation in Eastern Europe but receive far less notice in the US where Professor Gottfried resides; his work has, however, started to attract greater attention after the election of Donald Trump. Prof. Gottfried’s last contribution to the Sydney Traditionalist Forum was to its 2015 Symposium (“quo vadis conservatism, and do traditionalists have a place in the current party political system“) titled “Paleoconservatism: A Vanishing Traditional Right.”

Endnotes:

- “The Year in Review: 2016, Year of the Pivot” SydeyTrads – weblog of the Sydney Traditionalist Forum (blog) (2 January 2017) (accessed 29 January 2017) at ¶ 5.

- David Brooks, “Donald Trump, the Great Betrayer” New York Times (online) (4 March 2016) (accessed 29 January 2017).

- David Brooks, “I Miss Barak Obama” New York Times (online) (9 February 2016) (accessed 29 January 2017).

- Michael Goodwin, “Romney is too much of a coward to say what’s really on his mind” New York Post (online) (3 March 2016 @ 11:5) (accessed 29 January 2017).

- Jonathan Chait, “Why, Exactly Is Trump Driving Conservatives So Crazy?” New York Magazine (March 2016) p. 22.

- Bertrand de Jouvenel, On Power F. Huntington (trans.) (New York: Viking, 1949) p. 268.

- Carl Schmitt, Legalität und Legitimität (2nd ed., Berlin: Duncker und Humblot, 1968) pp. 9–11, 31.

- Kevin D. Williamson, “The Buchanan Boys” National Review (online) (4 February 2016 @ 4:00AM) (accessed 29 January 2017).

- Scott Greer, “National Review Writer: Working-Class Communities ‘Deserve to Die’” The Daily Caller (online) (12 March 2016 @ 12:12PM) (accessed 29 January 2017).

- Arnaud Imatz, Droite/gauche: Pour Sortir de l’Équivoque (Paris: Pierre-Guillaume de Roux, 2016) p. 117-83.

- Paul Gottfried, The Strange Death of Marxism: The European Left in the New Millennium (Columbia Missouri, University of Missouri Press, 2005).

- Arnaud Imatz, op. cit., p. 272.

- Ed Pilkington, “Obama angers Midwest voters with guns and religion remark” The Guardian (online) (14 April 2008 @ 21:13 AEST) (accessed 29 January 2017).

- Abby Phillip, “Clinton: Half of Trump’s supporters fit in ‘Basket of Deplorables’” Washington Post (online) (9 September 2016) (accessed 29 January 2017).

- See further, the writer’s upcoming book: Revisions and Dissents (Northern Illinois University Press, 2017).

- Benjamin Disraeli, Sybil or The Two Nations – Oxford World’s Classics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998) p. 65.

- See the seminal work on this subject by Michael Novak, The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1982).

Citation Style:

This article is to be cited according to the following convention:

Paul Gottfried, “Viewing the political scene from the end of 2016 and into 2017” SydneyTrads – Weblog of the Sydney Traditionalist Forum (11 February 2017) <sydneytrads.com/2017/02/11/2017-symposium-paul-gottfried/> (accessed [date]).

Dear Paul: It is always a pleasure to read your work. Your final sentence implies (or anyway I infer from it) that Trump’s electoral victory, if not itself revolutionary, is an event in something like a cascading political reorientation of the Western world that might bear the characterization “revolutionary” – or rather “counter-revolutionary.” My sense of mainstream commentary on Trump is that the profundity of his defeat of two political parties and a monolithic propaganda industry that slavishly does service for the Left has not really dawned on most observers. May I ask, please, whether you see Brexit, Trump, a probable victory for the Freedom Party in the upcoming Netherlands elections, and the rising popularity of Marine Le Pen as, indeed, a genuine turning of the tide? And do you regard such developments as radical or merely as elements in a superficial and cosmetic rearrangement of the establishment?

Tom,

In response to your intricately constructed question, the answer is a resounding “yes.” I do believe that Trump’s victory and his continued willingness to defy the multicultural establishment represents a further turning of the tide that began with Brexit and the rise of populist parties in Western Europe. I remain optimistic that we are not witnessing what you describe as a “superficial and cosmetic rearrangement of the establishment.” By the way, your references to Remi Brague have led me to look for his books online. He is obviously someone I should be reading.