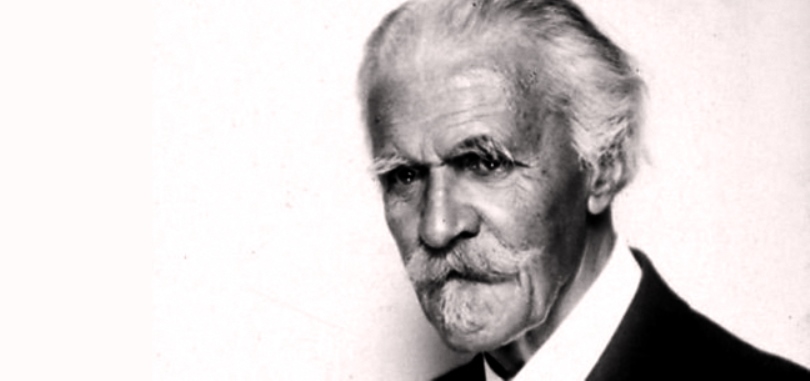

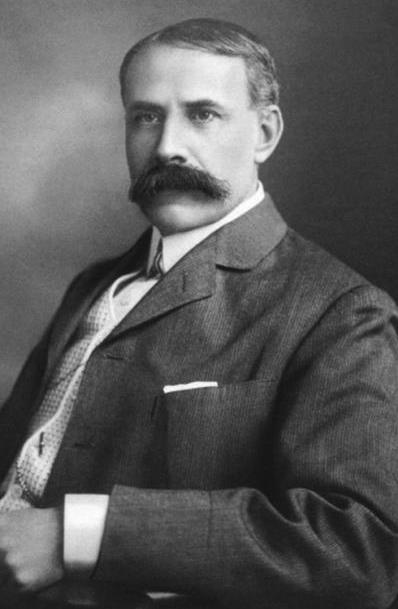

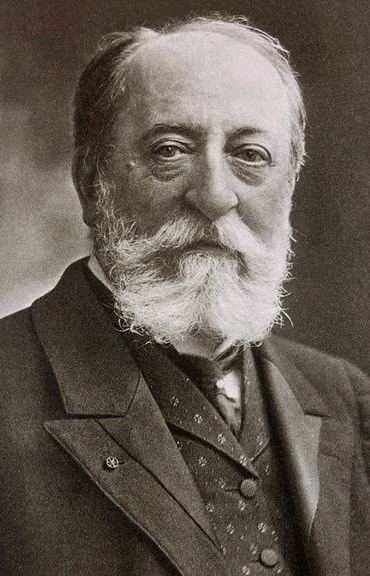

Vincent d’Indy (1851 – 1931), a close contemporary of Sir Edward Elgar (1857 – 1934), studied under César Franck (1822 – 1890) at the Paris Conservatory. On Franck’s death, d’Indy became the acknowledged guardian and continuator of his teacher’s musical heritage and something like a public dignitary of the arts in France. Like Elgar although less conspicuously in his national context, d’Indy upheld the fervent Catholic faith into which he had been born; like Elgar, d’Indy believed in the monarchic principle, finding himself increasingly alienated from the national-democratic dispensation of the Twentieth Century. As in the case of Elgar, again, d’Indy’s reputation rides on his mastery of two genres – symphonic music (both the symphony itself and the symphonic poem) and the oratorio; and like Elgar’s music, d’Indy’s has struggled without much success to export itself beyond its native frontiers – a pity because its beauty is so great and so refined. Like Elgar, finally, d’Indy stands out as something of a paradox: Deliberately modern in the early phases of his creativity, when he offended standing tastes, but later on in an altered context a deeply conservative artist who tended to codify – no doubt with good reason – the assumptions of his own earlier achievement. Unlike Elgar, however, who hailed from the provinces, d’Indy belonged from birth to the metropolis of his country, Paris; and, able to boast of aristocratic ancestry, never struggled to achieve full integration in his society, but found a ready welcome. Differing once more from Elgar, d’Indy flourished in a pedagogical environment. He founded the Schola Cantorum in Paris (1894) and served as its chief administrator until his death, at which time, however, his music seemed old-fashioned and stodgy to a generation fascinated by the shallow sarcasm and insouciant burlesque of les six. That d’Indy’s music in fact transcended its time, its persistence over the decades since his death eighty-seven years ago fully proves.

César Franck

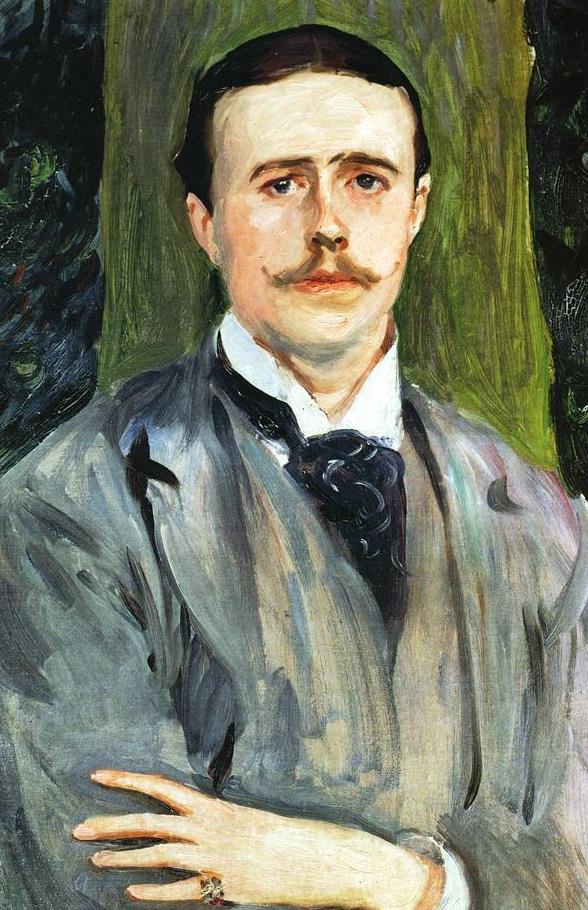

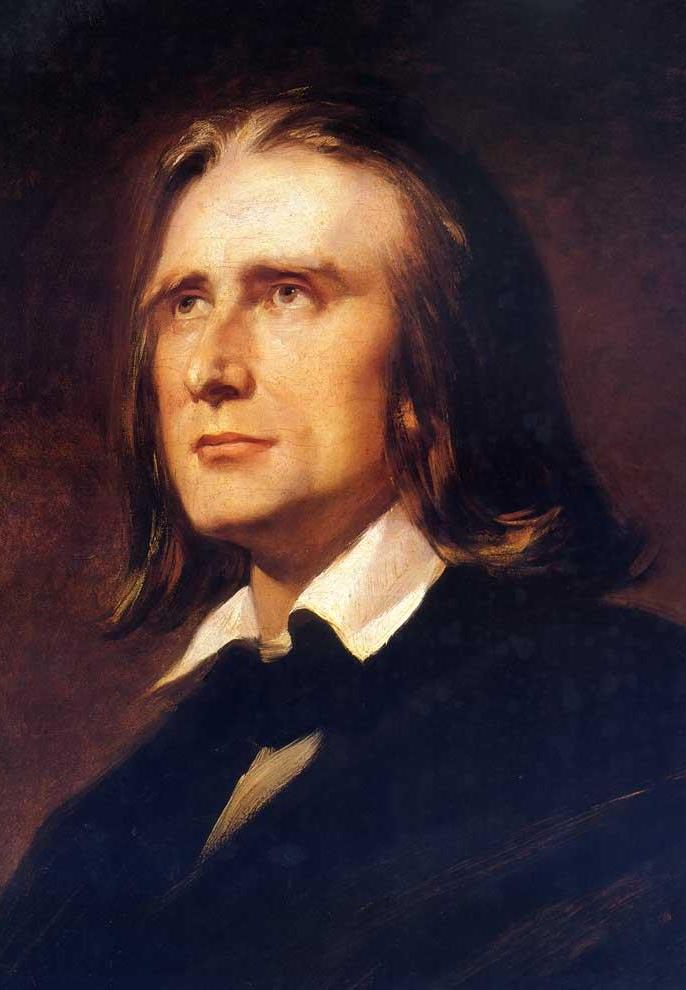

One further parallelism that assimilates d’Indy and Elgar is that while both managed to position themselves as national composers, distinctively French on the one hand and distinctively English on the other, each evolved for himself a musical idiom that absorbed a decidedly foreign influence – that namely of the Franz Liszt-Richard Wagner School, with the emphasis heavily on Wagner. D’Indy attended the 1876 premiere of Wagner’s Ring at Bayreuth when he had not yet celebrated his thirtieth birthday; later he would receive a redoubled impression from the ritual magnificence Wagner’s last music-drama Parsifal (1882), which influenced Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius (1900), as in that work’s Prelude.1 Concerning d’Indy, and in reference to Parsifal, René Dumesnil writes in his Histoire de la musique illustrée (1934) how, “Il aurait pu prendre pour devise le mot Kundry: dienen, server – mais c’est la musique française qu’il a toujours et partout servie, même contre ceux qui prétendaient, avec Saint-Saëns, effacer d’un trait de plume, á l’occasion de la guerre, jusqu’au nom de Wagner.” (“He could have taken for his motto the word of Kundry: dienen, to serve – but it was French music that he always and everywhere served, even against those who claimed to want, on the occasion of the war, as did Saint-Saëns, to delete the very name of Wagner.”) In an age of political correctness, d’Indy’s insistence on separating German art from German militarism shines out like a beacon. His notion of cultural rather than political synthesis recommends itself in an age of stringent bureaucracy.

Sir Edward Elgar

Laurence Davies writes in Paths to Modern Music (1971) that “d’Indy was easily the most learned and uncompromising of the French Wagnerians, an irritatingly perverse man who insisted upon attacking what he called ‘Boche Art’ at the same time as he was propagandizing madly for his idol.” Davies remarks that d’Indy’s Schiller-inspired “lyric drama” Le Chant de la Cloche (1885) strongly resembles Wagner’s Meistersinger because in it d’Indy “fell back on a guild of craftsmen and a rigged competition” just as in Fervaal (1885) he conjured “an oath of chastity and a magic garden” right out of Parsifal. The composer’s biographer Louis Borgex writes in Vincent D’Indy – Sa Vie et Son Oeuvre (1913) that La Chant is indeed a dramatic work: “Nous n’hésitons point à écrire ce qualificatif que l’on a appliqué trop à des actions purement extérieures, c’est là un puissant et noble drame dont le champ d’action est la Vie.” (“We do not hesitate to write this description, which is applied too much to purely external actions; this is a powerful and noble drama whose field of action is Life.”) D’Indy’s purely orchestral works owe a debt to Wagner, too, in their conceptions of harmony and orchestration, but in these scores astute listeners will detect also the formal inspiration of Liszt, who had already exercised his spirit on Franck, who in turn exercised his spirit on d’Indy. Even the works that d’Indy called symphonies (there are three of them canonically) behave formally rather more like large-scale symphonic poems in the manner of Liszt than like the symphonies of Ludwig van Beethoven or Johannes Brahms. D’Indy indeed succeeds Liszt even before Richard Strauss although music-historians usually credit Strauss with being the continuator of the Lisztian symphonic-poem innovation. But what exactly is le Wagnérisme – French Wagnerism?

Richard Wagner

Wagner danced a tango with Paris, attracted to it because it represented in its theaters and resident composers of the mid-century the pinnacle of opera. Opera in turn represented the pinnacle of musical success and fame. If Wagner could make it there, to quote a vulgar lyric, he could make it anywhere. For its part the City of Light only seemed to rebuff and humiliate him. Wagner lived in Paris, and in humiliating poverty, twice, once with his first wife Minna from 1839 to 1842 and again as a bachelor from 1859 to 1862. During the first sojourn, which ended in the usual flight from creditors, Wagner composed Rienzi, which with the help of Giacomo Meyerbeer he managed to get produced at Dresden, and Der Fliegender Hollander,2 but he otherwise made no impression on the local scene. During the second sojourn, Wagner succeeded in staging Tannhäuser at the Paris Opera, but with ambiguous results. In a fit of absurd petulance, members of the Jockey Club, objecting to the placement of the ballet at the conclusion of the first rather than the second act, disrupted the proceedings. The claque, most of them rowdy bachelors, attended opera almost solely to see the young female dancers in their paces. Otherwise they retired to the lobby to drink. Thus many of them missed the erotic spectacle, the Venusberg Bacchanale, which constituted their sole interest because Wagner had, as it were, misplaced it. After two more performances, Wagner withdrew the work and decamped for Prussia. He had nevertheless made a strong positive impression on a number of publicly influential people, even as he had rallied the distemper of the snobs and hooligans.

Charles Baudelaire

While the Paris Tannhäuser production might have proven itself a disaster, a concert of orchestral extracts under Wagner’s own baton at the Salle des Italiens struck deeply into the rising Symbolist sensibility among French artists. Poet Charles Baudelaire (1821 – 1867), the very innovator of Symbolism, left a notable account of the occasion in his essay on “Richard Wagner and Tannhäuser in Paris” (1862). Baudelaire writes how, “Je me sentis délivré des liens de la pesanteur, et je retrouvai par le souvenir l’extraordinaire volupté qui circule ans les lieux hauts.” (“I felt myself delivered from the ties of gravity, and I remembered the extraordinary voluptuousness that circulates in remote altitudes.”) Baudelaire experienced “une clarté plus vive,” “l’idée d’une âme se mouvant dans un milieu lumineux,” and “une extase faite de volupté et de connaissance, et planant au-dessus et bien loin du monde naturel” (“a vital brilliance”; “the idea of a soul moving in a luminous space”; “an ecstasy, melded of happiness and insight and voyaging beyond this natural world”). The aura of religiosity and mysticism that came later to hover about Tristan und Isolde, Das Ring, and Parsifal already makes itself felt in Baudelaire’s remarks. While Baudelaire’s Symbolist poetics seemed avant-garde in its context of the mid-Nineteenth Century, Baudelaire regarded himself and his work – and by extension Wagner and his work – as electively reactionary. He was reacting against what he perceived as the withdrawal of meaning from an increasingly vain and insipid, a steadily bureaucratizing and soulless, world.

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin

For Baudelaire, as his words indicate, the experience of hearing Wagner’s music in concert entailed much more than a psychedelic vision, no matter how powerful. The poet knew something of Wagner’s theories and therefore understood that the new idol’s art implied a cultural, even a political, as well as an artistic agenda, nothing less in toto than the revival of the sacred. Of Wagner’s verbal aspect, Baudelaire writes: “De même, les poëmes de Wagner, bien qu’ils révèlent un goût sincère et une parfaite intelligence de la beauté classique, participent aussi, dans une forte dose, de l’esprit romantique. S’ils font rêver à la majesté de Sophocle et d’Eschyle, ils contraignent en même temps l’esprit à se souvenir des Mystères de l’époque la plus plastiquement catholique.” (“The libretti of Wagner, no matter that they reveal a sincere taste for and a perfect comprehension of classical beauty, also incorporate a strong draught of the romantic spirit. However much they remind us of Sophocles and Aeschylus, they also force our memory back to the Mysteries of Catholicism in its formative era.”) Baudelaire wrote prophetically, in that Wagner, who began as a Communist and an atheist, became progressively more Christianizing in his orientation, a trend that would culminate twenty years later in Parsifal, a “Sacred Stage-Consecration Performance.”

Joseph de Maistre

The Wagner who appealed so strongly to Baudelaire’s younger countryman, d’Indy, was the very Wagner of Baudelaire, the Wagner deeply aware, as he wrote in his pamphlets, of the degeneracy of the modern age and of the contrasting intactness of the traditional societies either of ancient Greece or Gothic-Christian Europe. Baudelaire would have been aware of an irony in Wagner’s passionate interest in the knightly sagas and the legends of the Holy Grail. These bore a distinctly French imprint, even when Wagner bypassed the literary original to make use of a later, German-language source, as in Tristan und Isolde or Parsifal. The irony somewhat mitigates Davies’ interpretation of d’Indy as shaking one fist at “Boche Art” while extending an open hand to Bayreuth. It was a case of productive tension rather than of irresolvable contradiction. D’Indy differentiates himself from his idol in another way. Whereas Wagner embraced far-left, republican, and even communistic politics in youth before turning to the right in later life (he befriended Bukharin); d’Indy, for his part, found his convictions early and adhered steadfastly to the monarchic principle, to Maistrian reaction, and to Catholic Christianity. D’Indy fully shared with the later Wagner, however, the conviction that the present lacked character and made way for vulgarity and corruption. D’Indy thought with Wagner that the resurrection of art, particularly musical art, at a high level of seriousness would have actual, social and cultural consequences. As Borgex writes: “L’auteur du Chant de la Cloche n’a jamais caché la grande influence de Wagner exerça sur lui pendant une partie de sa vie, mais en même temps il n’a jamais cessé de chercher à s’affirmer. Il suivi son impulsion bienfaisante qui l’amena tout naturellement à évoluer peu à peu vers las complète révélation de sa personnalité.” (“The author of the Chant de la Cloche never concealed the great influence of Wagner exerted upon him during a part of his life, but at the same time he never ceased to seek to assert himself. He followed his beneficent impulse which naturally led him to evolve gradually towards the complete revelation of his personality.”)

Jacques-Émile Blanche

The sudden interest in Wagner’s art in France articulated itself in diverse phenomena: Not only in numerous items of journalism, including Baudelaire’s essay, but in the wide circulation of Wagner’s operatic scores in piano reduction, and the appearance of French compositions imitating the extended harmonies and blended orchestrations of Lohengrin and Tannhäuser, as well as operas on Gothic and medieval themes. In French Music from the Death of Berlioz to the Death of Fauré (1951), Martin Cooper notes that Emmanuel Chabrier’s Gwendoline (1886) is “a monumental essay in ‘Nordic’ poetry” and that Edouard Lalo’s Roi d’Ys (1888) draws on “a Breton legend which might well have commended itself to Wagner.” Catulle Mendès, who supplied Chabrier with his libretto, published his study Richard Wagner in 1886. The Revue Wagnérienne ran from February 1885 to July 1888, its roster of editors and contributors indicating the currency of its dedicated topic: Aside from Mendès and among others – Jacques-Émile Blanche (editor-in-chief), Charles Bonnier (writer), Pierre Bonnier (psychiatrist), Houston Stewart Chamberlain (English husband of Wagner’s step-daughter Eva), Édouard Dujardin (playwright), Joris-Karl Huysmans (novelist), Stéphane Mallarmé (poet), Stuart Merrill (poet), Pierre Quillard (poet), Algernon Swinburne (poet), Paul Verlaine (poet), Charles Vignier (poet), Villiers de l’Isle Adam (playwright), and Téodor de Wyzewa (aesthetician). According to Davies, these things amounted to so much “ideological furor,” but Baudelaire’s astonishment was neither ideological nor only a furor; it was the response of genuine sensitivity to a colossal phenomenon – and the same goes for d’Indy.

Franz Liszt

D’Indy met Liszt in 1873 and, as previously mentioned, attended the premiere of Wagner’s Ring at Bayreuth in 1876. Liszt was, by that time, a Catholic reactionary although less committed to monarchy than d’Indy. Two works, the symphonic poem La forêt enchantée (1878)3 and the symphonic triptych Wallenstein (1870 – 1881), record d’Indy’s vital reaction to the Lisztian-Wagnerian “music of the future.” La forêt enchantée, after a ballad by Johann Ludwig Uhland, predates by two years Franck’s composition Le chasseur maudit,4 also Uhland-inspired and given to the depiction of a magical forest-realm and events therein. The panoply of New German School effects makes itself evident in d’Indy’s score: The intensely nocturnal atmosphere of Tristan Act II, the hunting horns of that opera and of the earlier Tannhäuser, aviary displays in the woodwinds, as in Siegfried, and the ever-present chromaticism of the harmonies. The opening bars of La forêt enchantée indeed seem to echo those of Das Rheingold,5 if only briefly. D’Indy’s “voice,” moreover, exceeds Liszt’s voice in fluency and elegance; where one of Liszt’s symphonic poems remains episodic, d’Indy knits the events of his program seamlessly together in a continuous flow of voluptuous yet classically controlled musical narrative.

Friedrich Schiller

The ambitious Wallenstein,6 after Friedrich Schiller, consists of three panels, the first of which, “Le camp de Wallenstein,” much rewritten, goes back to an early “Piccolomini Overture.” D’Indy added “Max et Thécla” and “La mort de Wallenstein” later. Where La forêt enchantée takes root in Gothic folklore, Wallenstein taps the chronicles of the Religious Wars of the Seventeenth Century. In Wallenstein, d’Indy incorporates music of the period, anticipating his subsequent use of French folksong and Gregorian chant. It might justly be remarked that while Liszt incorporated chant and folksong, Wagner almost never did, the one exception being his use of the Dresden Amen in the last act of Parsifal. Wallenstein reflects d’Indy’s conviction that music must avoid the merely decorative; that it should participate in the continuum of civilized life, whether by communicating with the realm of legend or that of history. The link to Schiller is not incidental because Schiller precedes and likely influences Wagner in believing that, in a modern context, art has gained precedence over religion. Insofar, then, as one wished to foment a reestablishment of religion, as Schiller argues in The Aesthetic Education of Mankind (1797), it would be through the medium of art. Schiller’s drama with its themes of love and betrayal works up to a tragic climax, on which, of course, it bestows an aura of sublimated beauty. D’Indy’s instrumental climax – a kind of apotheosis – at the conclusion of “La Mort de Wallenstein,” aims at a similar transfiguration. In “Le camp de Wallenstein,” d’Indy employs the tune from the Thirty Years War that Hindemith would later appropriate in his Symphonie: Mathis der Maler (1934).7 The two works – d’Indy’s and Hindemith’s – would work well paired in a concert. Perhaps some enterprising conductor will give it a try.

Charles Bordes

When d’Indy with Charles Bordes and Alexandre Guilmant established the Schola Cantorum to be a school for composers and performers that would concentrate on instrumental and orchestral music rather than opera, he began his project of realizing his ideals in a functioning institution that would compete with the other conservatories already in existence. D’Indy asserted the absoluteness of counterpoint as the basis of compositional excellence; he insisted that musician-composers should know not only music but also the history of music – and alongside all that be well grounded in the other arts and the humanities. D’Indy had concluded that a truly French music, reflecting France’s Catholic civilization, would find its natural soil in the Gregorian repertory and in regional folk music. Music, as d’Indy saw it, should participate in all the central institutions of a society, beginning with the Church, and that in so doing it would contribute to the moral health of the nation. Counterpoint functions as a powerful symbol of the complex Christian civilization that invented it. In counterpoint, many voices speak at once, all of them individual and recognizable, but although they speak at the same time, they speak as components in a structure that both highlights and assimilates their differences. As counterpoint originated in sacred music in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries, its migration to secular music means that secular music remains rooted in sacred music. D’Indy remarks in his study of César Franck (1906) that: “L’origine de la musique, comme celle des tous les arts… est incontestablement d’ordre religieux. Le premier chant fut une prière. Louer Dieu, célébrer la beauté, la joie et même la terreur religieuses, fut le seul objet de toutes les œuvres artistiques durant près de huit cents ans.” (“The origin of music, as of all the arts… is incontestably of a religious order. The first song was a prayer. To worship God, to celebrate beauty, the joy but also the terror of religion was the sole object works of art for close to eight centuries.”)

Alexandre Guilmant

D’Indy’s emphasis on distinctive regional folk-music sources indicates his appreciation that the French nation had gradually forged itself through the union of smaller polities and local dialects, each with its proper lore and custom. Although d’Indy’s own music would become progressively less Teutonic, his ideas about music as a moral and cultural force remain identifiably Wagnerian. There were scoffers. Camille Saint-Saëns issued a pamphlet (1919) on Les Idées de Monsieur D’Indy, in which he mocked what he portrayed as his subject’s benighted reactionism, as exemplified by the textbook Cours de composition (1912). Saint-Saëns writes that d’Indy would “assimiler l’Art à la Foi religieuse” and he declares that “on pourrait lui observer que le Pérugin, que Berlioz, à qui manquait cette Foi, n’en furent pas moins d’admirables artistes même dans le genre religieux, mais passons” (“assimilate Art to religious Faith”; “one might observe to [d’Indy] that neither Pérugin nor Berlioz, although both lacked faith, was for it a less admirable artist in the religious genre, but we let it pass”). Concerning Berlioz, anyway, one senses despite the conventional irreligion a sense for the psychic profundity of religious ceremony – for example, in the Grande Messe de Morts (1838). As for Saint-Saëns – he shared Berlioz’s skepticism, but he lacked the elder composer’s sense of ritual. Perhaps it is purely a coincidence that Saint-Saëns was not a deep, but merely a decorative, composer, no matter the gratifying brilliance and nuanced wit of his art. One has only to listen comparatively to any of Saint-Saens’ tone-poems and any of d’Indy’s to hear the difference. For Saint-Saens the literary impulse furnishes the occasion for amusing musical narrative, with rather obvious, but of course dazzling, effects.

Camille Saint-Saëns

D’Indy’s own Symphony in B-Flat Minor (1904)8 sometimes called the Second Symphony, illustrates its author’s notion of abstract music as an expression of civilization – the equivalent in tones of a Gothic cathedral – and as fully capable of inspiring in its auditors a spiritual response similar to that elicited by grand religious architecture. Cooper judges the score “one of d’Indy’s most solid and logically constructed”; and he detects in it “reminiscences of Götterdämmerung in the development of the first movement and of Parsifal in the slow movement.” Davies, hewing to his stingy assessment of d’Indy, calls the same work as “stifling, intimidating.” Both commentators wrote at a time when opportunities to hear the symphony were few. Now that the score enjoys three or four recordings, listeners in reassessing it will want to correct Davies. D’Indy builds the Symphony in B-Flat on two germinal motifs heard at the outset of the First Movement, one chorale-like, the other song-like; indeed, the composer contrives that each of the remaining three movements should extract its thematic material from the two motifs, which return in complex counterpoint at the end of the Fourth Movement. Thus all four movements join in unity, with development throughout – a symphonic condensation of Wagner’s plan in the Ring tetralogy. Un-Wagnerian, however, is the Symphony’s Finale, which d’Indy conceives monumentally on the model of a Bach-like prelude and fugue with a chorale, for where will one find a fugue in Wagner? D’Indy’s symphony excels Franck’s lone Symphony in D-Minor (1889)9 in its subtlety of construction as well as in its consistent seriousness from beginning to end. Needless to say, d’Indy would have rejected such a judgment out of respect for his teacher.

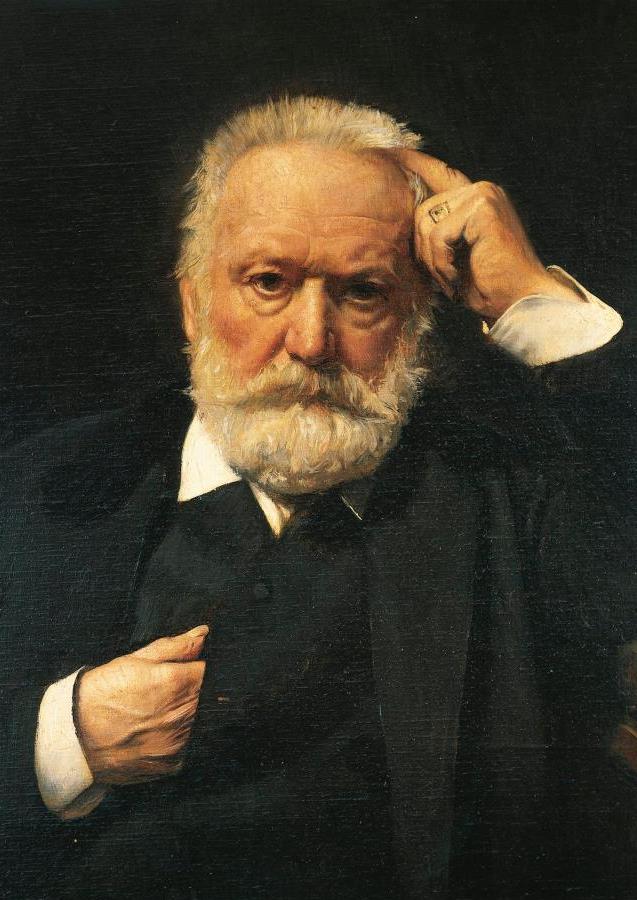

Victor Marie Hugo

Jour d’été à la montagne (1905)10 testifies again to d’Indy’s creative power at its height. Like Wallenstein and Symphonie Cévenole (redubbed Symphony No. 1)11 Jour is a symphonic triptych, an orchestral nature-portrait akin to Claude Debussy’s Mer (1902)12 and to other roughly contemporaneous scores such as Frederick Delius’ Song of the High Hills (1911)13 and Richard Strauss’ Alpensinfonie (1916).14 The three sections are: Aurore (“Dawn”), Jour (“Full Day”), and Soir (“Evening”). The program, related to Victor Hugo’s poem “Ce qu’on entend sur la montagne” (“What one hears on the Mountain”), which had also inspired Liszt, presents a religio-metaphysical allegory setting the aspects of human existence, as seen and heard from the mountaintop, against a spiritual-universal backdrop. Aurore represents the rising sun’s dispersal of the fog as a figure of the awakening of higher consciousness. Jour has a middle-section in which the far-away musical revels of a village fête impinge on the heights. Soir deftly incorporates one of the Gregorian chants for the Feast of the Assumption. The work’s literary associations extend to d’Indy’s own manifesto for serious composers, as quoted by Cooper: “Before all else the artist must have Faith – faith in God, faith in his art – because it is faith which spurs him on to knowledge and it is by means of this knowledge that he can mount ever higher in the scale of being, to the term of his whole nature, God.” D’Indy would also insist, in another statement quoted by Cooper, that “the artist must be inspired by the sublime.” A passage from Hugo’s poem suggests its own appositeness (the translation is Henry Carrington’s):

| C’était une musique ineffable et profonde, Qui, fluide, oscillait sans cesse autour du monde, Et dans les vastes cieux, par ses flots rajeunis, Roulait élargissant ses orbes infinis Jusqu’au fond où son flux s’allait perdre dans l’ombre Avec le temps, l’espace et la forme et le nombre. Comme une autre atmosphère éparse et débordé, L’hymne éternel couvrait tout le globe inondé. Le monde, enveloppé dans cette symphonie, Comme il vogue dans l’air, voguait dans l’harmonie. |

Music it was, ineffable and deep, Which vibrates, flows, and round the world doth sweep, And in the skies immense, its waves make young, In large and larger orbits rolls along; Till in the depth its billows reach the shade Where time, space, number, form, are lost and fade. Like a new atmosphere through space dispersed, Th’eternal hymn the total globe immersed: The world, encompassed in that symphony, As though the air did through that music fly. |

Hugo’s images, which must have endeared themselves to d’Indy, constitute a late-Romantic version of several venerable ideas, not least the ancient cosmological notion of a supersensible Music of the Spheres that sufficiently sensitive people might access by disciplined apperception – or that might be vouchsafed them in the form of grace. Mountaintops figure in mythic narrative and mystic initiation: The high hills provide a place for revelation whether heathen or Christian; the heights are where the holy men ensconce themselves and where pilgrims must go in order to consult the monasteries and shrines. Hugo’s figure of the “hymne éternel” invokes both a cosmo-theological notion of the world as a unity in which the parts fit themselves to one anotehr harmoniously – and an element of counterpoint, in the pattern of which the basso continuo gives the upper strata of the voices their harmonic foundation. The modern sensibility regards such ideas as fictional at their best but more likely as superstitious in the most pejorative sense. Modernity is a very late superimposition on the understanding of cosmic order and the place of humanity therein. Hugo, who was modern enough to be an ardent republican, nevertheless remained open to the experience of tradition and to the canonical symbolizations thereof. If Hugo’s expression befell a Twenty-First century mentality as a bit hackneyed, that impression might be explained by recourse to Hugo’s attempt, in a spiritually impoverished age, to recover a rich but lapsed intuition in terms understandable to his audience. The same might be said for d’Indy. Even where, in d’Indy’s musical symbolization, he falls short, his attempt strikes the listener as supplying its own justification. Perhaps there is always something tragic in Romanticism, whether that of Hugo or d’Indy: It makes a valiant and inspiring stand against a tide that it cannot stem – and on behalf of a cause that is bigger than itself.

Claude Debussy

(June 1908)

D’Indy’s vision, Romantic, Medieval, and Roman-Catholic, assimilating the validity in pre-Christian philosophy and lore, stands thoroughly at odds with the Twentieth-Century modernity into which the composer’s life extended by three decades. Once more, the parallelism with Elgar seems appropriate to remark. We have a better picture, indeed, of Elgar, than of d’Indy, for a good part of d’Indy’s creative effort went into the opera-oratorios that he launched regularly throughout his authorship, and these works have fallen into near-complete oblivion. Elgar’s oratorios, on the other hand, retain a niche in the concert repertory – in the United Kingdom, at least – and on record. Le chant de la cloche (1883), Fervaal (1893)15 L’Etranger (1906), and La légende de Saint Christophe (1915), the last a “sacred drama in three acts,” would make a fascinating comparative study put in place alongside The Light of Life (1896), The Dream of Gerontius (1900), The Apostles (1903), and The Kingdom (1906), but only a much-cut 1962 performance of Fervaal exists on disc. Elgar’s Symphony No. 1 in A-Flat (1908)16 uses the same structural devices as d’Indy’s Symphony No. 2 in B-Flat although Elgar’s score, full of marches and catchy tunes, hews closer to democratic art than d’Indy’s rather aristocratic score. No one would ever have accused d’Indy of being, as some said of Elgar, a “Salvation-Army Composer.” On the other hand, the influences of folk-music are stronger in d’Indy than in Elgar, especially in d’Indy’s later works, like the Poème des Rivages (1921)17 and the Diptyque Méditerranéen (1926)18 in both of which d’Indy comes to terms brilliantly with the Impressionism of Claude Debussy. One thinks of Debussy’s Three Nocturnes (1899)19 or Iberia (1908).20

Frederick Delius

Occasionally d’Indy could be subjective and personal in his carefully projected mood. The best examples are probably to be found in the tone poem Saugefleurie (1884)21 described as “a legend for orchestra after Robert de Bonnières” and in the later Souvenirs (1906)22 described a “poem for orchestra.” Saugefleurie has its roots in de Bonnière’s book Contes de fées (1881), which versifies old stories from the countryside. D’Indy and de Bonnières had been childhood friends. The atmosphere, as any number of program-writers have acknowledged, is heavily Wagnerian, but one also senses that the score is replete with childhood memories and reflects its composer’s nostalgia for the stage of life in which it is still possible to be deeply moved by the tragic plight of a fairy princess. The score of Souvenirs, for its part, directly declares its personal character. D’Indy dedicated it to the memory of his first wife, Isabelle, also his cousin, who died from the effects of a lesion in her brain in 1906. D’Indy makes use of a theme that had appeared in Jour d’été à la montagne, renaming it “la thème de la bonne aimée.” The grief of the work is all the more powerful for being so restrained. One might observe as well that the general objectivity of d’Indy’s achievement is heightened by his moments of relaxation from the struggle for civilization, but then the affect in Souvenirs is not exactly that of relaxation.

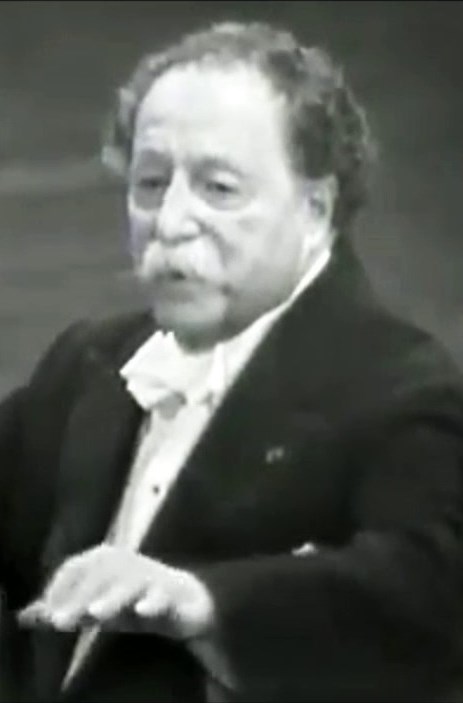

Pierre Benjamin Monteux

D’Indy entangled himself in the Dreyfuss Case by siding stridently with the anti-Dreyfussards. He thereby tainted himself with the mark of a scapegoater who disdaining the better angels of his nature went with the crowd. It should be entered into the ledger on d’Indy’s behalf, however, that despite his rhetoric he maintained perfectly cordial relations with his Jewish friends and students, even dedicating Symphony No. 2 to Paul Dukas (1865 – 1937), whose own Symphony in C-Major (1906)23 adheres to the compositional principles of the Schola Cantorum. D’Indy’s Jewish friends appear to have reciprocated the civility, and they must have had their reasons. Pierre Monteux, who stemmed from an old French-Jewish family and who had known the composer on friendly terms, made the first recordings of the Symphony in B-Flat and Istar (a set of symphonic variations in which the theme is only revealed in the final section)24 with the San Francisco Symphony in 1942. This was eleven years after d’Indy’s death. As Monteux’s recording sessions took place at the nadir of Allied fortunes and the acme of Axis fortunes in the European Theater, it would seem unlikely that the conductor considered the composer as anything like the equivalent of a then-contemporary anti-Semite. He must have thought of him as a decent human being. Students of d’Indy like Guy Ropartz (1864 – 1955)25 Albéric Magnard (1865 – 1914)26 Leevi Madetoja (1887 – 1947)27 and Albert Roussel (1869 – 1937)28 upheld the master’s dispensation well into the Twentieth Century. Finnish, Romanian, and Latvian composers made use of the d’Indy Tradition. Cole Porter (1891 – 1964) was a d’Indy student and a Schola Cantorum graduate. A passage in George Gershwin’s American in Paris (1928) seems to echo the far-away fête of Jour d’été à la montagne. The Schola Cantorum exists today and has a global presence.

René Guénon

It might be useful to understand d’Indy as a “Practical Traditionalist,” someone whose attitude toward modernity resembled that of his later countrymen René Guénon, on the one hand, and Henri de Lubac on the other, but who also enjoyed creative genius as a musician and possessed the élan vital to found a functioning institution for the embodiment and continuation of his ideals – just as Wagner was both a composer of music-dramas and the conjuror of a functioning dramaturgical institution at Bayreuth. If d’Indy’s opera-oratorios remained largely inaccessible musically at present, as they do, it would be possible nevertheless to consult their libretti, every one of which is concerned with religio-metaphysical problems such as transcendence and redemption. Fervaal, which has recently (2009) been given a concert-performance under the baton of the redoubtable Leon Botstein,29 even seeks to synthesize Christianity, Paganism, and Islam – shades of Guénon – in a Maurice Maeterlinck-like drama set in a Pagan Celtic realm. Fervaal involves the failure of a heathen oracle,30 Kaïto, and the advent of the Gospel – or rather a mystic form thereof with its own esoteric rituals. Fervaal31 combines the sacred aura of Parsifal32 with the eroticism of Tristan und Isolde33 rushing already into a kind of Liebestod in the first of its three acts, concluding it in the third act. In the manner of Maeterlinck, d’Indy makes the action heavily symbolic and demands the most that stagecraft can supply of rich ornament. D’Indy, like Wagner, wrote his own libretti or adapted existing material, as in La Chanson de la cloche (Song of the Bell), based on Schiller’s Lied von der Glocke (1798). Surveying the libretti, one can only conclude that d’Indy’s taste, as affirmed by his biographer, inclined to the ultra-Romantic, but that these texts reflect their author’s interest in the depth and validity of endangered traditions, not least those of that peculiar mélange of heathen saga and Christian piety so often on display in medieval romance.

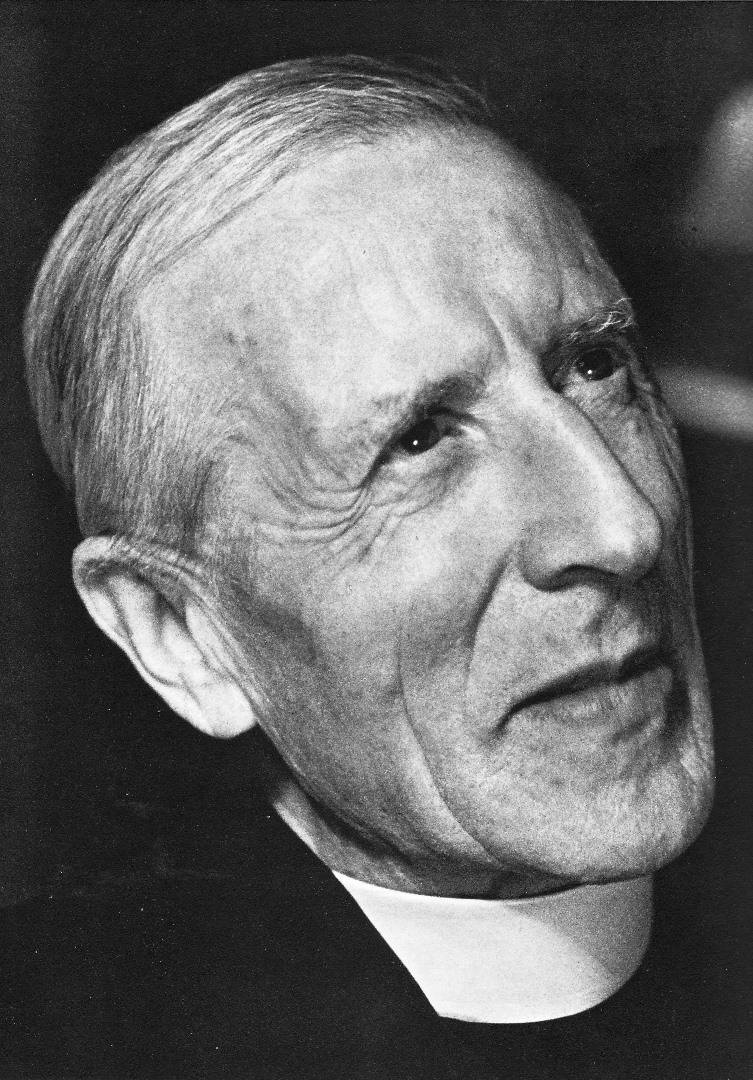

Henri de Lubac

D’Indy, a musician of no little spiritual and philosophic insight, calls to mind another French conservative of a later generation who although mainly a philosopher possessed a deep knowledge of music and wrote often about music – Gabriel Marcel (1889 – 1973), the Christian, that is to say Catholic, Existentialist. Readers will find a number of references to d’Indy in Marcel’s essays on philosophy and music. Marcel, for example, holds Fervaal in high esteem. In his essay “Reflections on the Nature of Musical Ideas: The Musical Idea in César Franck” (1920), Marcel seeks to establish the living character of the musical motif or theme. For Marcel (in the translation by Maddux and Robert Wood) the musical idea, whether a melody or a harmonic progression, presents itself to the subject as another subject, a person, with whom the listener makes acquaintance. Marcel pushes his analogy quite far. As in any long-enduring human relationship, the relationship between the subject and the musical idea nourishes mutually, “for if it is correct to say that we put into the idea more and more of ourselves, it is nonetheless legitimate to affirm that we incorporate it into ourselves more and more intimately.” According to Marcel, “There is no reason to choose between an interpretation according to which we have caused something of our own life to pass into [the musical idea] and an interpretation which says that the idea itself has enriched us.” In this way music – and every art – contributes to what Marcel calls “spiritual community,” without which a society must fall ill and pass away. In an essay on “Bergson and Music” (1925), Marcel, referring to Wagner, argues that music at its highest point of expression “prolongs our memory into a Theogony and reestablishes a continuity between individual duration and the duration of the universe.

Gabriel Honoré Marcel

In the same essay on Bergson, Marcel mildly criticizes d’Indy. The context of the criticism is Marcel’s assertion that “the profound idea… seems to come from afar” and that it “corresponds… to what I would like to call relaxation coming from on high.” In Marcel’s judgment, and here he makes specific reference to d’Indy’s string quartets, the composer of Fervaal sometimes contrives his development rather than opening himself to inspiration or grace coming from on high. Marcel owns the right to his view. Connoisseurs and aficionados, and they have increased in number over recent decades, would vindicate d’Indy. Take the String Quartet No. 1 in D Major (1890):34 The score begins with a reference to the main motif of Beethoven’s Grosse Fugue, about as ungainly a musical idea as one might recall, but by the time the Finale reaches its denouement, the music has indeed relaxed into prolonged decrescendo of remarkable sweetness. The late Poèmes des rivages, for orchestra, which Marcel could not have heard at the time his essay first saw its way into print, likewise invites – and fully justifies – the description of relaxation coming from on high. What would new performances of La légende de Saint Christophe and Le chant de la cloche, and recordings based on them, reveal? It is by no means a foregone conclusion that posterity has, in letting them fall into oblivion, given them due diligence. In 1970 the number of d’Indy recordings in the bins of the now vanished record stores would have been quite small – the Symphonie Cévenole and a few other works only being represented. In 2017, d’Indy’s discography is rich, including a fine account of the orchestral works in six volumes on the high-production-value Chandos label in performances by the Iceland Symphony Orchestra under the direction of British conductor Rumon Gamba! Gamba’s survey encompasses the previously little-known Symphony No. 3, “De Bello Gallico” (1916).35 I strongly recommend d’Indy to serious listeners who enjoy Franck and Debussy and who would like to make the acquaintance of another voice, different from but equivalent in expressive validity to theirs.

– Thomas F. Bertonneau is an American intellectual and professor. He has taught at a variety of institutions, and has been a member of the English Faculty at State University of New York, Oswego, since 2001. His articles and essays have appeared in a diverse array of scholarly journals including William Carlos Williams Review, Wallace Stevens Journal, Studies in American Jewish Literature, North Dakota Quarterly, Michigan Academician, Paroles Gelées: UCLA French Studies, and Profils Americains. He was a major contributor to the English section of The Brussels Journal. More recently, his work has appeared in The University Bookman, the John William Pope Center for Higher Education Policy as well as the websites The People of Shambhala and The Orthosphere.

– Thomas F. Bertonneau is an American intellectual and professor. He has taught at a variety of institutions, and has been a member of the English Faculty at State University of New York, Oswego, since 2001. His articles and essays have appeared in a diverse array of scholarly journals including William Carlos Williams Review, Wallace Stevens Journal, Studies in American Jewish Literature, North Dakota Quarterly, Michigan Academician, Paroles Gelées: UCLA French Studies, and Profils Americains. He was a major contributor to the English section of The Brussels Journal. More recently, his work has appeared in The University Bookman, the John William Pope Center for Higher Education Policy as well as the websites The People of Shambhala and The Orthosphere.

Endnotes:

- The writer recommends Paul Marie Théodore Vincent d’Indy’s Prelude to The Dream of Gerontius by the New Philharmonia Orchestra, Conducted by Sir Adrian Boult (date unknown); see also Wilhelm Richard Wagner’s Prelude to Parsifal, the Philharmonia, Conducted by Francesco D’Avalos (date unknown).

- See Richard Wagner, Overture to the Flying Dutchman, The Metropolitan Orchestra, Conducted by James Levine (date unknown).

- See Vincent d’Indy, Opus No. 8, La Forêt enchantée, Orchestre Philharmonique des Pay de Loire, Conducted by Pierre Dervaux (date unknown).

- See César Frank, Le Chasseur Maudit, Movement No. 44, Orchestre du Capitole de Toulouse, Conducted by Michel Plasson (date unknown).

- See Richard Wagner, Das Rheingold, Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Conducted by Georg Solti (date unknown).

- See Vincent d’Indy, Opus No. 12, Trilogie d’Après Schiller, Orchestre Philharmonique des Pay de Loire, Conducted by Pierre Dervaux (date unknown).

- See Paul Hindemith, Symphonie “Mathis der Maler”, London Symphony Orchestra, Conducted by Jascha Horenstein (1972).

- See Vincent d’Indy, Symphony No. 2 in B-flat major, Opus No. 57, Orchestre du Capitole de Toulouse, Conducted by Michel Plasson (date unknown).

- See César Frank, Sinfonieorchester, Frankfurt Radio Symphony, Conducted by Marc Minkowski (2015).

- See Vincent d’Indy, Jour d’Été à la Montagne, Iceland Symphony Orchestra, Conducted by Rumon Gamba (date unknown).

- See Vincent d’Indy, Symphonie sur un Chant Montagnard Français, Performed by Torma Gabriella and the Budapesti Filharmóniai Társaság Zenekara (date unknown).

- See Claude Debussy, La Mer, Cleveland Orchestra, Conducted by Vladimir Ashkenazy (date unknown).

- See Frederick Delius, The Song of the High Hills, BBC Symphony Orchestra and the BBC Symphony Chorus, Olivia Robinson (soprano) and Christopher Bowen (tenor), Conducted by Andrew Davis (2011).

- See Richard Strauss, Alpensymphonie, Opus No. 64 “Gefahrvolle Augenblicke”, Berliner Philarmoniker, Conducted by David Bell (date unknown).

- See Vincent d’Indy, Fervaal, Bern Symphonieorchester, Conducted by Srboljub Dinić (2009).

- See Edward Elgar, Symphony No. 1, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Conducted by Vernon Handley (1979).

- See Vincent d’Indy, Poème des Rivages, Luxembourg Philharmonic Orchestra, Conducted by Immanuel Krivine (2006).

- See Vincent d’Indy, Diptyque mediterraneen, Op. 87 “I. Soleil Matinal”, Luxembourg Philharmonic Orchestra, Conducted by Emmanuel Krivine (c. 2006).

- See Claude Debussy, Three Nocturnes, Cleveland orchestra, Conducted by Vladimir Ashkenazy (date unknown).

- See Claude Debussy, Images pour Orchestre No 2 “Iberia”, London Symphony Orchestra, Conducted by Claudio Abbado (dated unknown).

- See Vincent d’Indy, Saugefleurie Opus No. 21 “After Robert de Bonnières’s Tail”, Strasbourg Philharmonique Orchestra, Conducted by Theodor Guschlbauer (c. 1993).

- See Vincent d’Indy, Souvenirs, Opus No. 62 “Poeme for Orchestra”, Monte Carlo Philharmonic Orchestra, Conducted by James DePreist (date unknown).

- See Paul Dukas, Symphonie en ut Majeur, BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, Conducted by Yan Pascal Tortelier (date unknown).

- See Vincent D’Indy, Istar, Variations Symphoniques, Opus No. 42, San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, Conducted by Pierre Monteux (1945).

- See Joseph Guy Ropartz, Symphony No. 1 “Sur un choral Breton”, Orchestre Symphonique et Lyrique de Nancy, Conducted by Sebastian Lang-Lessing (date unknown).

- See Lucien Denis Gabriel Albéric Magnard, Symphony No. 3 in B-flat minor, Opus 11, Orchestre du Capitole de Toulouse, Conducted by Michel Plasson (date unknown).

- See Leevi Madetoja, Symphony No. 2 in E flat major, Opus 35, Iceland Symphony Orchestra, Conducted by Petri Sakari (date unknown).

- See Albert Roussel, Symphony No. 3 in G minor, Opus 42 , Royal Scottish National Orchestra, Conducted by Stéphane Denève (date unknown).

- See Vincent D’Indy, Fervaal, Opus 40 Act I “Fervaal, pourquoi rester dans ce jardin?”, Orchestre Radio-Lyrique, Conducted by Pierre-Michel Le Conte (1962).

- See Vincent d’ Indy, Fervaal, Opus 40, Prelude to Act I, Paris Conservatoire Orchestra, Conducted by Charles Munch (2007).

- See Vincent d’ Indy, Fervaal, Opus 40, Act III Prelude, Sinfóníuhljómsveit Íslands, Conducted by Rumon Gamba (2015).

- See Richard Wagner, Parsifal, Act I Prelude, Wiener Philharmoniker, Conducted by Georg Solti (date unknown)

- See Richard Wagner, “Tristan und Isolde” Prelude and Liebestod, Wiener Philharmoniker, Conducted by Christian Thielemann (2003).

- See Vincent d’Indy, String Quartet No. 1 in D major, Quatuor Joachim (2001).

- See Vincent d’Indy, Symphonie No. 3 en Ré majeur Opus 70 “Sinfonia Brevis de Bello Gallico”, Sinfóníuhljómsveit Íslands, Conducted by Rumon Gamba (date unknown).

Leave a comment