This is the text of a presentation given to the Sydney Traditionalist Forum on 23 November 2018 by Prof. Ted Sadler, as part of the Forum’s “Quarterly Inquiry Series”.

♣

Did the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990’s mean not only that the Western powers had ‘won the Cold War’ but that the ideological system of the West had triumphed decisively over its only serious rival, communism? This was the question posed by Francis Fukuyama in his 1993 book The End of History and the Last Man, and indeed, as the title of the book suggested, Fukuyama was inclined to think – and apparently still thinks – that liberal democracy did triumph at this time, at least symbolically and in the realm of ideology, so that ‘the end of history’ had been reached. Naturally there was much misunderstanding of Fukuyama’s meaning, especially on the left, so that even Jacques Derrida was moved to point out that this century of liberalism’s triumph had been as bloody as any other period of history. But as Fukuyama had to point out again and again, his argument was only that the idea of liberal democracy had proved victorious, even if its practice throughout the entire world was still a long way off. For Fukuyama, religion was no longer a source of geo-political conflict, nationalism had been discredited as an ideology by the First World War, while racialism had ended as a viable ‘belief-system’ with the defeat of the Axis powers in 1945. After the Second World War conflict of historical significance was simplified into the opposition between communism and liberal-democratic capitalism, and within fifty years the issue had been decided: the whole world, it seemed, now ‘wanted’ liberal-democratic capitalism.

Francis Fukuyama

Doubtless Fukuyama was too optimistic about how soon the ‘end of history’ would be consolidated worldwide. And doubtless too he did not pay sufficient attention to what a few years later Samuel Huntington called the ‘clash of civilizations’ or the ‘clash of cultures’ – in which connection Islam’s willingness to embrace the ‘end of history’ is especially questionable. These matters aside, however, there is today, twenty-five years after Fukuyama’s book appeared, a great deal in it worthy of thought, even if one comes to conclusions in part very different from Fukuyama. It is now a quarter of a century since the Cold War passed into history. In the West the younger generations, including the politicians, have never known the opposition between the ‘free world’ and ‘communist tyranny’. Of course political conflict within Western countries is now as intense as ever; indeed it is often maintained that these countries are now internally divided to an unprecedented degree. What then is the cause of this division? Fukuyama suggests an answer, although he himself hardly takes up the question. Can it be that the fundamental conflict in politics now revolves around what Fukuyama describes as the ‘end of history’, that is to say whether liberal-democratic capitalism really is or should be the stopping point and ‘fulfilment’ of history? Granted that liberal democrats felt they had triumphed, granted that they had indeed triumphed over the Soviet Union and Eastern European communism, granted even that ‘old-style’ Marxism had forfeited much of its appeal ideologically in the West (and even more so in the former territories of communism), were there still powerful forces that did not want to press forward to the ‘end of history’?

Jacques Derrida

The situation is complicated, however, largely confounding the hackneyed political categories of ‘left’ and ‘right’. Radicals who would like to overthrow capitalism have not disappeared in the West, and sometimes still have an attachment to communism in the old style together with its heroes Marx, Lenin and Stalin. Indeed several of the most influential contemporary Western intellectuals – Alain Badiou and Slavoj Žižek for instance – are open admirers of Lenin and Stalin, a position that is easier to maintain since the memory of communist Russia has faded away among young people. It is true that far-leftism is not organized into political parties, but these days there is a large disorganized ‘army’ of leftists who have a strong influence on culture – one can reasonably surmise that what attracts such people to this modern form of militancy is the desire for comprehensive destruction, including the sanctification of violence for the cause. The significance of these ‘far-leftists’ and ‘anarchists’ is mostly indirect but nevertheless effective, by pulling mainstream socialists and liberals further ‘leftward’ with successful political demands that systematically erode any concept of a stable centre of values. In the meantime conservatism in politics has been weakened, partly due to the fact that the Soviet Union and the communist states of Europe no longer exist but mostly due to the success of relativism and liberalism in framing the terms of all discourse. Indeed it is now becoming clear just how much, from the Second World War until 1990, the shape of Western politics was governed by the Cold War. Fukuyama was right about this, and right in thinking that, after 1990, a new consensus arose – not total, but significantly prevalent in ‘elite’ circles, – according to which the phenomenon of authoritarian communism was an unfortunate hump on the main track of history, which has now ‘settled’ – ideologically at any rate, if not practically – in the end-state of democratic liberal capitalism. It is interesting to note, incidentally, that Fukuyama had come to this view in an article from mid-1989 prior to the fall of the Berlin Wall – he was not wrong in believing that the time of reckoning for the Soviets and Eastern European communists was fast approaching.

Samuel Huntington

In trying to understand the landscape of contemporary Western politics the economic record of post-1945 capitalism is obviously of central relevance. For the main reason that fewer people nowadays call for the ‘overthrow of capitalism’ – socialist parties allow this plank of their platform to quietly lapse – is that capitalism, notwithstanding the exacerbation of inequalities of wealth – has delivered something of an economic miracle, ‘lifting millions out of poverty’ and expanding the middle class. Apart from die-hard communists, ‘leftist’ agitators these days mostly favour a harsher taxation regime together with redistribution measures, confident that wealth-creating will not cease to cover needs. This attitude has allowed former conservatives to drift to the left in the new left centrism seen all around the Western world: Germany, France, Spain, Holland, Scandinavia, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and even to a considerable extent the United States. Indeed in the United States the Democratic Party, not the Republican Party, is the party of big money, and everywhere the ‘leftist’ parties are preaching the gospel of growth and wealth while accusing their adversaries of threatening the economic system.

Alain Badiou

Who then are the adversaries of the ‘left-centrism’ that is fast defining ‘normal politics’ in the contemporary West? Here again Fukuyama is useful, for he explains this left-centrism through its orientation to what he calls the ‘universal homogeneous state’: the adversaries of left-centrism, accordingly, are those who do not want and do not believe in this state – this state which is ‘the end of history’ because it represents the ‘end of ideology’. In this connection it is significant that, as Fukuyama admits, the idea of the ‘universal homogeneous state’ originates with Alexander Kojève, the Russo-French Hegelian Marxist who after 1945 was one of the architects of the European Common Market. Kojève, who in his early post-war writings was already looking ahead to what would become the European Union, believed that the ‘good society’ could be defined chiefly through two desiderata: reasonable material-economic conditions and security on the one hand, and universal ‘recognition’ of each citizen by every other citizen (universal mutual respect) on the other hand. This indeed became the program of the European Union, and more broadly of ‘globalists’ everywhere: in essence the belief was that free-trade would deliver affluence, and this combined with political liberalism would provide the indispensable conditions for the pursuit of happiness. Both elements in this equation required that ‘old prejudices’ be broken down: restraints of trade due to national borders, and obstacles to ‘recognition’ due to inherited traditions. By securing affluence, and gradually erasing the prejudices that divided peoples, historical conflict would end. The ‘end of history’ would arrive, or a new type of history would begin which would eventually encompass the globe. At the present time – Fukuyama is right about this – it appears that the ‘arc of history’ is towards this universal homogeneous state. It appears, to an increasing number of people anyway, perhaps the majority in Western countries, that this is an ‘objective’ and ‘necessary’ tendency, that it is something like the ‘law of progress’ which can be denied or resisted only by the ignorant and bigoted.

Slavoj Žižek

In the not-so-distant past political conflict within Western countries centred on the opposition between capitalist-liberal and socialist-egalitarian sentiments. This has now given way to the opposition between ‘progress’ and ‘reaction’, mostly defined at a cultural level. The homogenization process of the universal homogeneous state means that society is defined as an indiscriminate aggregate of individuals stripped of any other cultural identity: ethnicity, nation, tradition and religion – this at the same time that ever-increasing rhetoric is dedicated to the sacrosanctity of ‘culture’ and ‘beliefs’ . All individuals, it is assumed, are capable of taking their place in the economy as workers, consumers, tax-payers and benefit-recipients, and with cultural identity, including most crucially religious identity, relegated to secondary status, social harmony will be guaranteed by ‘tolerance’. This is contemporary liberalism. The assumption is that the social and cultural identity of the universal homogeneous state is nothing in particular: this absence of identity is called ‘multi-culturalism’, a euphemism for the cultural vacuum that is liberalism. Of the course the liberal champions of the universal homogeneous state do not feel ashamed; on the contrary they are proud of the emptiness of their ‘ideal’ and are zealous for this emptiness.

Liberals themselves, of course, do not say they are affirming a vacuous negativity, but insist that their supreme value is freedom. The ideal liberal state is supposed to provide not just economic well-being for everybody, but the freedom of individuals to do what they like, say what they like, think what they like, live however they like, providing it does not infringe on the freedom of others. Liberalism does not posit any goal in life apart from maintaining and exercising the freedom to whatever goal one sets for oneself; this is often called the Western ‘way of life’. It is true that liberalism also values ‘compassion’, because the liberal ideal of the ‘pursuit of happiness’ presupposes that individuals are in a position to do so, which they may not be owing to their material conditions. There is indeed a ‘collectivist’ dimension to liberalism which may be in some degree of tension with the desideratum of individual freedom. This important matter aside, however, what could be called the ‘liberal faith’ is the faith in no ultimates except liberalism itself. In this sense liberalism is a formal creed: it makes no pronouncements about particular goods but is at bottom a second-order attitude about value-choices, namely that unless they ‘harm’ others they are all ethically equal. Liberalism is a philosophy about choice but does not itself make a choice except for itself. In the context of the project of the universal homogeneous super-state – this project that has superseded communism or rather absorbed it and ‘validated’ it – liberalism is the belief that human happiness and ‘fulfilment’ will be reached through conscious recognition of the supreme value of free-choice at every level.

Alexander Kojève

The great difficulty in understanding the political and cultural situation of modernity – the continuing and never-ending ‘crisis’ – is due to the difficulty of understanding liberalism. Indeed even this word ‘liberalism’ is inadequate for comprehending the whole ideological-cultural-philosophical complex at the bottom of modernity. The word is not important, of course, if one understands the ‘thing’ – or the complex of things, the whole range of phenomena commonly subsumed under ‘liberalism’. Since the seventeenth century a new civilization, based on a new worldview and a new ‘philosophy’, has been growing in the interstices of the ‘Western’ civilization that for more than a thousand years was Christendom and for a thousand years prior to that ‘proto-Christian’ Greco-Roman civilization. This new civilization and new worldview can be reasonably called ‘liberalism’ as long as this expression is not tied too strictly to the political philosophies that have developed over this period and which are really secondary phenomena. For the essence of liberalism is the broad sense is nothing else than the philosophical relativism that began its work of disintegration even before 1600 and which has taken time to establish itself. It is now ascendant, but its work is still not done, and can never really be finished, because it runs up against resistance from reality. For reality will not be defeated by relativism, not at the abstract level of philosophical discourse and neither at the level of practical politics.

Liberalism, in this sense of relativism, has become the religion of the modern age. And at first sight strangely, given its declarations of tolerance, it has also become an extremely intolerant religion. For the liberals of today have defined liberalism as the simple truth that must be recognized by every sane human being. The new worldview of liberalism, so its exponents say and teach high and low, still has to contend with the ignorance and prejudice that survive from past periods. But, we are told, the growth of science, the Enlightenment, and the development of ‘progressive’ politics since the French Revolution, have made it impossible for anybody except the most retrograde elements of society to doubt the liberal worldview. Thus do liberals attribute political division and the ‘culture wars’ in the West to the recalcitrance of ignorant and ‘backward’ sections of the population. The 2016 Presidential election campaign in the United States showed this clearly, as did the ‘Brexit’ campaign of the same year in the United Kingdom: on the one side those wanting to march forward to the universal homogeneous state, on the other those who ‘do not believe’, that is to say, those who have not come to ‘believe in disbelief’, those not convinced that every form of traditional belief now stands discredited, those not enamoured of the new liberal ideal of emptiness and the pseudo-culture of multi-culturalism, those lacking faith in a new society of emptiness that identifies freedom with emptiness and looks to this emptiness, together with material prosperity, for the ‘meaning of life’. For the liberals of today, the ‘enemies of the human race’ are all those who do not embrace the project of the emasculation of meaning in the suicide of Western civilization.

Friedrich Nietzsche

The intolerance of modern liberalism is inevitable, because it is always going against the grain of the human spirit. It is true of course that liberalism indulges and caters for certain impulses in human beings; its ‘strength’ is that it ‘validates’ what people want according to the ancient Greek formula (attributed to Protagoras) that ‘man is the measure of all things’. For indeed the pursuit of emptiness is at bottom the same as the pursuit of any arbitrary thing – one is ‘open’ to everything, one ‘accepts’, ‘respects’, and ‘sympathizes’ with everything except for the spirit of ‘closure’ and ‘dogmatism’ which tries to impose values and standards that are ‘unnecessary’ and ‘out-dated’. The liberal worldview believes in a new type of empty human being who is stripped of all tradition, nationhood, racial and ethnic identity and especially of all religion. Already many of these new human types exist, or at least are trying to live according to this new model. But even Fukuyama, who seems to think that only by ‘becoming liberal’ can humanity vouchsafe a future for itself, cannot conceal a certain level of contempt for this new human, whom he calls, in the title of his book, ‘The Last Man’. This expression is taken from Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra, and refers to the exhausted state of humanity after the Death of God when the purpose of life has been reduced to materialistic (that is to say hedonistic) terms. For Nietzsche, these ‘Last Men’ are really unworthy of existence, for which reason he offers his own Superman ideal as the new ‘great hope’ for the human race. But while Fukuyama rejects the solution offered by Nietzsche, he understands, and up to a point shares, Nietzsche’s contempt for the type of human who has not only come to terms with, but actually celebrates, the universal hedonization of culture. Modern secular culture, especially when ‘fulfilled’ in the universal homogeneous state (or super-state), cancels out the divisions that have set people at war; on the other hand these divisions are based on values, traditions and ideals which form the very stuff of cultural meaning. Fukuyama cannot hide his embarrassment when in his book he tries to convince himself and his readers that the new liberal human being can still find life worth living: there remains economic and professional competition, artistic creativity, sport, and of course all kind of hobbies, among which may be included religion (being a member of a church becomes more or less equivalent to being a member of a stamp collectors’ society).

Hillary Clinton

Fukuyama’s inner resistance is obvious, but the problem – the reason that when all is said and done he holds to the universal homogeneous state – is that he cannot see any alternative. That the world has become or is well on the way to being one, is the fact from which he begins. And there can be no turning back. It is not simply that the potentially cataclysmic consequences of war now make people realize that they must accommodate and ‘tolerate’ each other. More fundamental than this is that economics and communications make the global world a fact rather than an ideal. However, to move from recognition of this fact to globalism as an ideology depends on making this fact – that people all over the world are aware of each other, trade with each other and try to understand each other – into a moral value capable of replacing traditional (especially religious) value-systems. In other words, economic and pragmatic values – which in the end are hedonistic – are asserted to be sufficient as a morality and system of meaning, at least when combined with the principle of liberalism as defended by Fukuyama and Kojève: the principle that human ‘fulfillment’ consists in prosperity plus the freedom of human beings to do what they like as long as they do not ‘harm’ others (this qualification reflecting what ‘respect’ comes down to according to liberalism). The same point can be made in respect of the slogans around ‘diversity’ that have come to dominate the cultural landscape in the West. For diversity is just a fact of life – to make a value out of it, as if life is more ‘meaningful’ on account of diversity, is logically absurd and contrary to common sense. People may ‘appreciate’ diversity or they may not; this is a matter of taste. Of course toleration of diversity is a moral value, even an important one, but this is quite different from valuing diversity as such. Moral valuation pertains to the reality or content of what is valued, but no content is indicated by ‘diversity’. A ‘diverse’ group of prison inmates – murderers, rapists, robbers, fraudsters, terrorists, of all races and ethnicities and ‘faiths’, is not superior to a racially homogeneous collection of saints. This is common sense, but so much has common sense been eroded in our relativistic age that many people do not understand it. ‘Multi-culturalism’ is widely taken to be ‘a culture’, for it is affirmed as the cultural identity of certain nations, including Australia. In fact multi-culturalism is just the more or less harmonious existence of different cultures, and is not itself a culture. It is rather liberalism that is a culture: the culture of tolerance for whatever individuals choose to put into the empty shells that are their ‘selves’. The modern ideology of liberalism, as articulated by Fukuyama, declares that the meaning of human life is simply the freedom of a materially prosperous person to fill their shell as they please. By the same token, those who do not share this belief and live by it are regarded – by Fukuyama too – as willfully ignorant of the necessary movement of history and as bound by bigotry to the prejudices of past periods.

René Descartes by Frans Hals

Contemporary liberals (multi-culturalists, relativists, proponents of the new universal homogeneous state) may or may not employ the term ‘civilization’ for their ideal social system. Not a few of them are worried by the idea that some societies are civilized and others are not, while they may also think that every so-called civilization in world history has been outrageously oppressive. In any case these liberals believe that the universal homogeneous state, when achieved, will be a ‘community’ grounded in real unity, including consciousness of common purpose. The resistance to this super-state naturally worries (indeed angers) the liberals but evidently does not shake their faith, for all over the Western world governments and mainstream political parties have ‘doubled-down’ in campaigns to overcome those who Hilary Clinton called ‘the deplorables’ – those who refuse to admit that traditional values and meaning-systems are untenable. The attempts to legislate tradition and religion out of existence have had partial success but only at the cost of the ‘tolerance’ that liberals pride themselves on. Here indeed liberals confront their ‘moment of truth’. The ‘community’ they want is supposed to be freely chosen because freedom is the only non-material value they recognize. Yet people are not necessarily choosing it! Will the ideal of freedom have to give way? Will the ideal of the universal homogeneous super-state have to be rethought such that it is not so ‘liberal’ after all? Will the new ideal of the empty human being who at least has freedom to choose have to be revised, to be replaced by the empty human being who is merely an economic actor and is assigned his place? And is such a system, such a ‘post-historical’ society of ‘Last Men’, capable of surviving? Could it survive even as a totalitarian Brave New World? Could it overcome the predictable challenge from those who will not give up their traditional values? Could it, for example, survive the challenge of a confident and resurgent Islam?

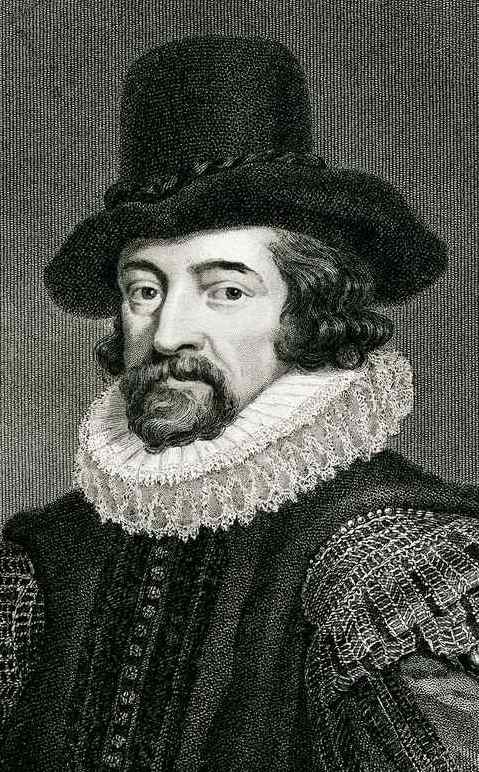

Most people acknowledge that over the last century much that belonged historically to the Western tradition has been discarded. But tradition has become so remote to so many people in the West that they do not understand what has been discarded. Living in the present, Westerners have lost a sense of what tradition and culture mean. For the first time in history many people feel that they do not have or need a tradition or even a culture. Western man has become uprooted and rootless, and has come to think of this condition as ‘normal’. It has come to be widely accepted that the ‘mature’ human being breaks out of tradition and achieves ‘autonomy’ in an ‘enlightened’ society. In the early seventeenth century already, René Descartes, often regarded as the father of modern philosophy, declared that everything belonging to tradition must be set aside in the rationalistic search for truth. A similar attitude was taken by the empiricists Francis Bacon and Thomas Hobbes, so that before the seventeenth century ended a tone had been set which has lasted to the present day: ‘truth’ is not to be found in religion or tradition or art but exclusively in science or in the logical deductions of a mind cleansed of ‘prejudice’. The Enlightenment of the eighteenth century looked to a new cosmopolitan super-culture that would replace Christianity: individuals would be uprooted not only from their national or ethnic or local traditions – which could only be the source of prejudices – but also from the similarly cosmopolitan super-culture of Christianity. The new mature enlightened individual would stand naked and proud ‘above’ all tradition, needing only his ‘freedom’ and prosperity. It is impossible to understand what is now happening in the Western ‘culture wars’ without looking back to the project of this new super-culture that formed in early modern times and has become the ‘faith’ of ‘modern civilization’. As Nietzsche knew, this is the decadent faith of the ‘Last Men’. The proponents of the universal homogeneous state are deluded, for they do not comprehend on what thin ice they are building. This is because, ultimately, they do not comprehend what man is. They believe that man can, and wants to, ‘live on bread alone’. They do not understand the spirit of man.

Francis Bacon

The future of Western civilization cannot be the way naïve liberals believe it will be. This is because the spirit of man will not acquiesce in it. People will not indefinitely consent to a culture of empty material prosperity: all the benefits, security, thrills, pleasures, entertainments, devices and diversions will not suffice. The idolatry which is inseparable from liberalism – for as Luther said, ‘man always has God or an idol’, and liberalism rejects God – will not satisfy man for very long. This means, then, that the less naïve liberals (who are not strictly speaking liberals any more) will have to take over the project, setting consent aside in totalitarian confidence, pushing ahead to the ideal of a universal homogeneous state comprised of empty but equal individuals – some being more equal than others. Totalitarianism is the only possible outcome of the liberal project as sketched by Fukuyama and Kojève. But even so it is a dream. For as the liberal spirit comes increasingly to dominate the West, the power to resist external challenges becomes weaker: the fundamental uncertainty characteristic of relativism makes people reluctant to acknowledge enemies and take measures against them. In practical contemporary terms, Western governments and a good part of the Western public do not want to believe that Islam has political designs on what are now Western countries and areas of influence; indeed many liberals are convinced that Muslims have a genuine grievance vis-à-vis the West, and that Muslim demands for ‘power-sharing’ in Western countries (through Sharia law) should be acceded to. There is in any case an ongoing process of cultural retreat in the West whereby Islam is consolidating at the expense of Christianity and quasi-Christian morality. To be sure, the official position of liberalism is that Muslims can be accommodated into the ‘cultural mix’ that is the modern West. But this presupposes that Muslims will want to practice their religion like liberals, namely ‘as a private interest’, this being the way that Christians too, and those belonging to every religion, are expected to conduct themselves. More so than other religions, however, Islam is political, and in the long run cannot be expected to reduce itself in the manner liberals demand. Given current trends, the likelihood is that Islam will continue to grow in Western countries until it gets to the point of a real power struggle against a culturally enfeebled West. The universal homogeneous super-state, whether envisaged along the lines of soft liberalism or hard dogmatic socialism, is thus not sustainable, because a state, and a civilization, depends on unity, and the de-spiritualized value-system of liberalism and socialism can never provide this.

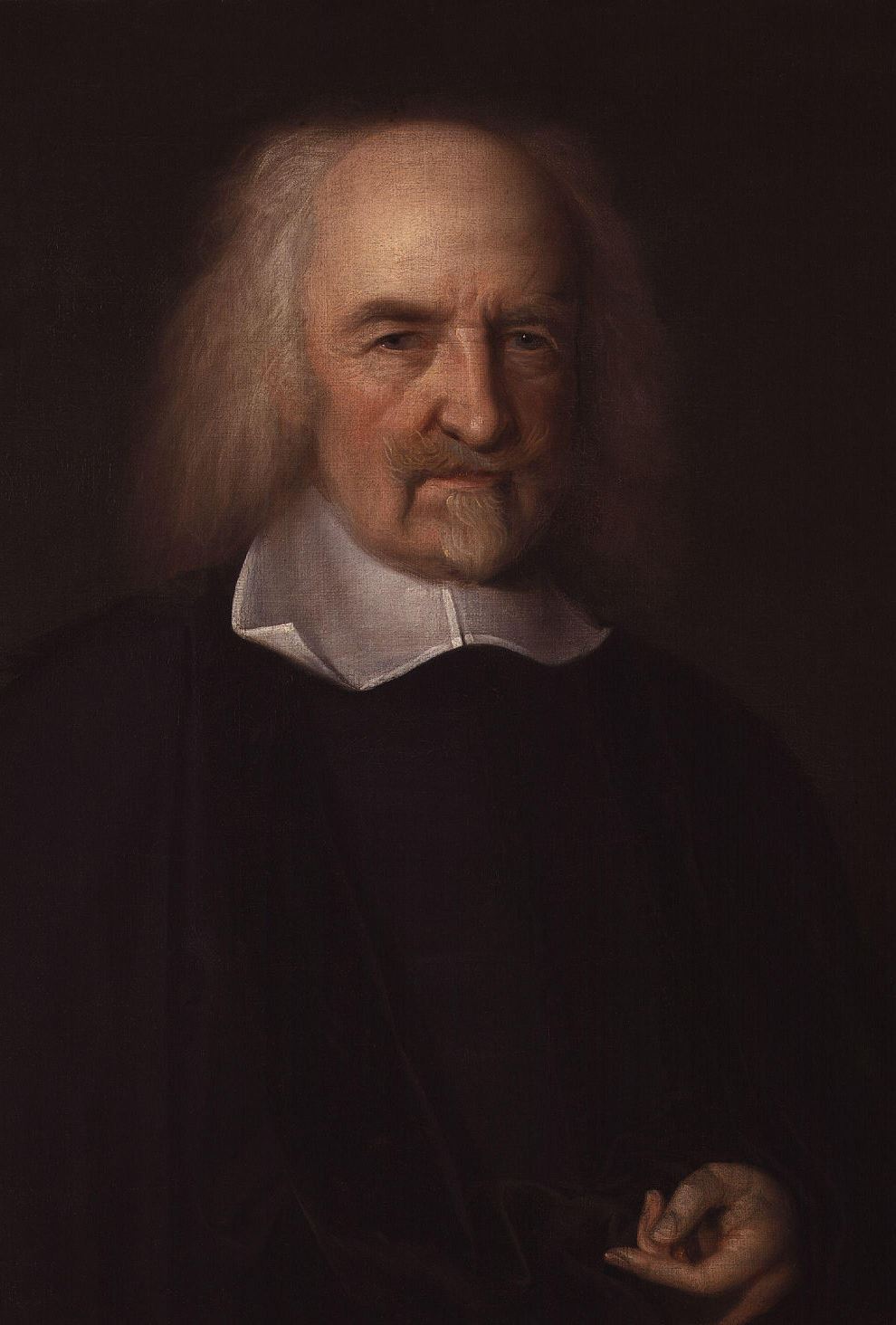

Thomas Hobbes by John Michael Wright

As much as the movement to a universal homogeneous state seems like a juggernaut, there have been and continue to be forces of resistance. The election of Donald Trump in the United States, the vote for Brexit in the United Kingdom, gains for some anti-EU parties in Western Europe, and strong anti-globalist sentiment in Eastern Europe, show that modern and postmodern liberalism cannot expect to go unimpeded from one triumph to the next. From the liberal point of view, of course, anti-globalism can be rooted only in the bigotry and ignorance of the past, and in time will fade away. It is vital, however, that opponents of globalism should not be content with temporary victories built on fundamentally unsound foundations. Of course the propaganda of liberal globalism excoriates nationalism as akin to fascism and Nazism, and this must be rejected as absurd – quite apart from the fact that the globalists themselves make all kinds of exceptions in their condemnation of nationalism – but it should be realized, nevertheless, that nationalism is fundamentally insufficient as a basis for culture and civilization. In the past, before Enlightenment secularism had done its corrosive work, the unity of Western civilization was guaranteed by the Christian religion. The same point applies to every civilization: only spiritual unity, expressed in a religion, can create or maintain a true culture as opposed to an unstable social amalgam. There is no inconsistency between a limited nationalism and spiritualism, indeed only the latter can hold nationalism back from the fetishistic forms it has taken on all too often.

It is a delusion to think that the universal homogeneous state – which in the end can be nothing other than a totalitarian society of debased humans – can be avoided by something less than religion or spiritualism. It is not a matter of ‘returning to the past’ but of distinguishing between the eternal and the temporal – over time new forms of religion will doubtless emerge, but this is not to say that traditional forms have not been, and do not remain, valid means for expressing eternal values. The great problem with Christianity today – this applies to other religions too but Christianity seems to be the worst case – is that it has compromised with the liberal and relativist spirit of modernity and has therefore disarmed itself as well as making itself less appealing to the mass of people who are in search of truth and meaning. The secularist culture of today is always browbeating, deriding, and attempting to punish those who oppose it. The non-secularists and non-liberals can therefore easily feel isolated, intimidated and threatened, possibly to the point of despairing submission. It should be remembered, however, that the secularists are so fanatical in seeking to root out every last remnant of spirituality because they understand the power of the spirit, even if reduced to a remnant. It seems that the juggernaut cannot be stopped, but this impression is based on a foreshortened historical perspective. Those who do not ‘believe in liberalism’ may not have any practical program for turning the juggernaut around. What they have to do is wait, and testify to the truth.

— Dr. Ted Sadler was born and currently resides in Sydney. Now retired, he lectured in philosophy at the University of Sydney, The Australian Catholic University, and the Catholic Institute of Sydney. He specializes in modern German philosophy and is the author of Nietzsche: Truth and Redemption – Critique of the Postmodernist Nietzsche (Bloomsbury, 2000) and Heidegger and Aristotle – The Question of Being (Bloomsbury, 2000).

— Dr. Ted Sadler was born and currently resides in Sydney. Now retired, he lectured in philosophy at the University of Sydney, The Australian Catholic University, and the Catholic Institute of Sydney. He specializes in modern German philosophy and is the author of Nietzsche: Truth and Redemption – Critique of the Postmodernist Nietzsche (Bloomsbury, 2000) and Heidegger and Aristotle – The Question of Being (Bloomsbury, 2000).

Bibliography (and comment by author):

In my view the historian Christopher Dawson provides incomparably the greatest insight into the cultural and spiritual crisis of the contemporary West. All his writings are of great value for understanding the history of Western civilization, but the most relevant for this essay are:

- Understanding Europe (CUA, 1952)

- Religion and the Modern State (Sheed & Ward, 1936)

- The Judgement of the Nations (CUA, 1942)

- The Crisis of Western Education (CUA, 1961)

Many relevant articles can be found in the archives of the following web-sites:

Leave a comment