I. The Question

Anyone possessed with a literary enthusiasm has read a poem written in the last half-century or so that made them wince with pain—a poem written by someone with a strikingly obvious penchant for the c-word, the f-word; for graphic depictions of sex or violence; anything ‘edgy’ and novel that this poet can cram into their verse. Poets have retired the old tools of the craft—beauty, rhythm, and contemplation, to name a few—and surrendered themselves to the power of shock. I’m going to make a very general assumption I have no evidence for, but nonetheless I think it’s worth considering: there’s a remarkable correlation between the rise of Post-Modernism and the decline of public interest in poetry. Most adults alive today have read a bit of Tennyson, Austin, Frost, Eliot, Yeats, or Plath. In their own time, these were literary giants with public reputations and considerable followings. Even the less-decorated and short-lived careers were in the public consciousness, at least among those of a certain level of education.

Today, our average English student has maybe read a little Seamus Heaney or Billy Collins, probably some Maya Angelou… But the great writers of our time fall under the radar even of those who are supposed to dedicate their lives to the art of literature! Imagine how this must reflect public opinion. I wonder how many adults could name a living poet they admire?

There’s no point in me lying and saying I never judge the ‘public’ for their poor taste in music and literature. How Taylor Swift and Fifty Shades of Grey can be so popular and yet we haven’t all perished in nuclear war is a mystery to me. But the ‘literati’ give the public very little choice: they produce very scarce poetry that the public consents to read.

Part of the reason for this disinterest or lack of awareness, I think, is that poetry has moved so quickly: massive ‘progress’ has been made in poetic content and style between the Modernist period (early 20th century) and the present. The difference between the Humanist/Enlightenment poets (Milton, Cowper) and the Victorians (Tennyson, Browning) is not so dramatic: both—and the movements in between—used strict form to express philosophical ideas, and these ideas were at least palatable to a large portion of the public. From the Modernists to the present, the change has been jarring. In the Post-Modernist period, we see little form and little philosophy. The Surrealists, Confessionalists, and Beat poets generally concerned themselves with formality neither in style nor in content. I do not intend to dismiss these movements, nor do I mean to imply that they and all other modern literary schools are uniform in this way, but it demands no stretch of the imagination to believe that Formalism is out of vogue among modern writers.

The question is whether this is the same for modern audiences.

II. Defining Classicism

As T.S. Eliot wrote in his essay, “What is a Classic?”:

I suppose that, to a modern European suddenly precipitated into the past, the social behavior of the Romans and the Athenians would seem indifferently coarse, barbarous, and offensive. But if the poet can portray something superior to contemporary practice, it is not in the way of anticipating some later, and quite different code of behavior, but by an insight into what the conduct of his own people at his own time might be, at his best. 1

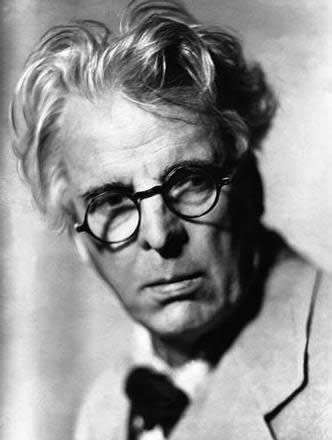

T. S. Eliot (b. 1888 d. 1965)

Likewise, a Classicist is one who hopes to write a classic.

What sort of ramifications does self-identification as a Classicist carry? Is it the vanity of an F. T. Marinetti declaring himself a Futurist and writing a manifesto for others to follow? Or the ruin we might expect if a young Chilean poet sat down one day and said to himself, “I’m going to be the next great Surrealist”? I don’t believe either of these are the case.

A Classicist is simply a writer who meditates on the importance and imminence of values and institutions—the traditions—that effect his people, but in a way that a foreign audience could consume and appreciate both as a voice of that particular culture and as an insight relevant to their own traditions. We might say Classicism is an attempt to realise a great Tradition that underlies all the lesser traditions upheld by the peoples who have inhabited the world since the beginning of human history. To understand those traditions we must first understand the artist’s relationship with his people—his Nation.

III. The Nation

Ireland, a nation whose identity was radically transformed during the period of High Modernism, is an excellent example of the relationship between art and the Nation.

W. B. Yeats (b. 1865 d. 1939)

In his day, William Butler Yeats was considered the voice of Ireland. Denis Donoghue went so far as to say that Yeats invented a country and called it Ireland; though this is a strong exaggeration, one must consider what a monumental impact Yeats must have made on the Irish consciousness. This perception of Yeats’s omnipresence is still common today. Though James Joyce was a revolutionary anti-Yeatsian, like any national revolutionary his vision for the Irish Nation could not be one of pure invention, but rather draw upon national traditions with which the public, who is never as a whole toward their country and people, may recognise and embrace.

As the Australian expatriate writer Christina Stead wrote, “… I firmly believe that every artist, writer and scholar lives for his country and does best when not cut off from his country. I believe otherwise they starve and wither.” 2

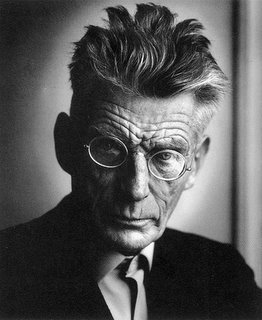

Contrast this to Beckett, who was a staggeringly un-Irish writer, often by his own design. He is both metropolitan and international while at the same having little artistic allegiance to his own country. A general theme of non-Classicist writers (think also of Imagist Ezra Pound and contemporary Situationist Gail Jones) is that their own works and their ‘disciples’ are almost tangential in the history of literature: part of the continuity, but formally and conceptually unique to a certain period. They are also tangential to their own nation’s literature: Ireland is proud of Beckett, and Australia of Jones (no one seems to wish to claim Pound), but the writers are not themselves national voices. To be a national voice, of course, that voice must address matters pertaining to a Nation, and a nation is a people united—for better or worse—by a certain culture, history, and institutions, which we may broadly label the traditions discussed in part IV. We’re likely to disagree with Stead’s declaration that their severance from a national consciousness ruins their work, but we understand the strength of the connection between Classicist and their Nation.

IV. Tradition

I made the claim that a Classicist is a writer that meditates on tradition. ‘Meditates’ is an important term to consider. A theoretical poet whose interaction with religion is that “religion is always and everywhere bad” is not a Classicist. For one, it is as objectively false to say that religion is consistently negative as is to say that religions and their adherents have never committed a despicable act.

The relationship between artistic Classicism and the philosophy of traditionalism is fairly independent of any loyalty to tradition, but not disinterested in them.

Once we grasp the relationship between tradition, the supreme ‘Tradition’, and the Nation, we may discuss how Classicists have addressed the question of these traditions. One tradition found in every nation across the world is religion.

James Joyce (b. 1882 d. 1941)

Consider once more James Joyce. While by no means a Roman Catholic apologist, his novels nonetheless grapple with the role of Roman Catholicism in Ireland, both where he perceives it has failed and where it has given the Irish people values, customs, unity, hope, and the power of will, among other positives I might more easily detect if I were Irish or Roman Catholic. His point of view is not dogmatic in any sense, and a Classicist is always conscious of the nuances involved in traditions of their people. If all traditions were all bad, then a whole people would themselves have to be ‘bad’; and, as we have observed, very few writers and audiences are willing to embrace such an idea—one overwhelming reason being that the general public isn’t composed of ideological automatons.

Conversely, though W. H. Auden was a thoroughly convinced Christian, his poetry isn’t simply text for a hymn awaiting the appropriate tune. When he addresses Christianity, he does not proselytise as a minister, but grapples with faith as a layman: for a Classicist is a master of no trade but life itself, and aspires to master nothing but his art and the perpetually-unreachable Truth.

Czesław Miłosz (b. 1911 d. 2004)

The fact is that certain approaches to religion may disqualify or greatly hinder one from becoming a Classicist. An anti-revisionist Leninist might find it difficult to compromise their ideology to criticise a certain individual or party with whom they are sympathetic. As Czesław Miłosz said of socialist realism, the artistic ideology of Stalinist Russia and the Eastern Bloc, “In the field of literature it forbids what has in every age been the writer’s essential task—to look at the world from his own independent viewpoint, to tell the truth as he sees it, and so to keep watch and ward in the interest of society as a whole.”3 Likewise, a ‘Bible-thumping’ Protestant fundamentalist may find it difficult to establish a moral paradigm not simply restating the views of whatever non-denominational denomination they follow. Of course it is not impossible, but dogmatism (and fundamentalism of any kind, Marxist or Protestant or whatever, is essentially a sort of dogmatism) undermines the sense of transcendence which great art necessitates. This isn’t to say those creeds are therefore wrong: Plato, the father of Western philosophy, despised poets for their sentimentality and poetry for its ability to derail rational thought. Likewise, the Puritans abhorred most art, not for its irrationality, but for the simple fact that there are more ‘Godly’ things to do than read and write novels. At worst, they could be vehicles for doubt and heresy, which is indeed how many dogmatists might interpret that which is luminous yet ultimately unknowable. In other words, I’m not saying that the test of an idea’s validity is how well it lends itself to Classicism or even poetry, only that some faiths and philosophies are more ‘poetic’ than others and certainly more compatible with Classicism.

Indeed, one conviction that underpins Classicism is a true sense of Mystery (alternatively called the ‘numinous’ or the ‘Sublime’). That is not to say Classicists lack conviction, only that mystery is an essential element of the Classicist’s experience.

V. Politics

It is important to keep in mind that, while tradition may have political implications, that isn’t necessarily the only context in which ‘tradition’ may be used. For example, many Anglo-Catholics—the fastidiously traditionalist wing of Anglicanism—are political liberals and even socialists. On the other end of the spectrum, thinkers such as Julius Evola might be so ‘traditional’ that the idea of sticking their noses into any realm of modern democracy or populist authoritarianism disgusts them.

Observe how widely read Eliot is. My experience has been that most people are aware of “The Waste-Land” or “The Love-Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”. This might be because previous generations were meant to read excerpts from one or both poems in secondary school, but they were likely also forced to read The Red Badge of Courage, and the name Stephen Crane does not linger even in the American consciousness like the name of T. S. Eliot across the Anglosphere.

Observe how widely read Eliot is. My experience has been that most people are aware of “The Waste-Land” or “The Love-Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”. This might be because previous generations were meant to read excerpts from one or both poems in secondary school, but they were likely also forced to read The Red Badge of Courage, and the name Stephen Crane does not linger even in the American consciousness like the name of T. S. Eliot across the Anglosphere.

What allows Eliot to resonate so profoundly with modern audiences? Why do so many Americans connect with a High Tory, Anglo-Catholic expatriate who wrote half of each poem in German, Latin and French? Even the literati, who would have absolutely nothing to do with Eliot’s philosophical conservatism, cherish him as a poet. As they should; he is a hauntingly fine writer. Still, it’s interesting that a poet so highly regarded in academia happens to be a stalwart reactionary, orthodox Christian, and anti-materialist: in essence opposed to everything the modern intellectual elite stand for.

As much as he would have resented the claim, Eliot did not only sing of himself—his disillusionment and genuine existential crisis sincerely engendered a sentiment held by a vast number of the Interwar and WWII-era public. In contrast with the public, his crisis was not so much that WWI shattered his illusion of modern society: he was inherently suspicious of liberal democracy and likely anticipated its collapse. Nor did he fight in the trenches as many of contemporaries had. His suffering at first stemmed from an overbearing thoughtfulness and pressing Gnosticism that made him miserable in the physical world, the “Waste-Land”. Yet his poetry resonated with his generation to the degree that he felt forced to rebuff much of the praise heaped on him for expressing what the laymen of the ‘Lost Generation’ could not.

A severely antagonistic voice might be inclined to say that his Christian faith rang true with the opiated masses, though we often forget that Eliot’s conversion did not come till after the ‘Waste-Land’ was written, published, and a critical success. “Ash Wednesday”, “Journey of the Magi”, and the Four Quartets are his great post-conversion poems, none of whose popularity can compare to his earlier work.

I would, confessing to be a severely protagonistic voice, say that Eliot is not so popular because, but rather in spite of his philosophical views—views which have set him against popular opinion since the end of the Glorious Revolution. If contemporary poets stake their claim in the need to express political opinions in verse, they are, in a manner of speaking, democratically safe, but artistically endangered. The public doesn’t seem to regard political manifestos in broken prose very highly, and adhering to a popular or progressive political creed is no guarantee whatsoever of amassing a considerable public audience. One writer’s politics doesn’t even seem to guarantee or disqualify an academic following.

What, then, does modern poetry contain that makes it a ‘Great Book’, a work of creative fictional or poetic genius that will be cherished for generations to come? And is this a Great Book the same as a Classic?

VI. Experimentation and Sustainability

In contemplating what constitutes a ‘great’ literary work we come up against two very different kinds of literature. Take, for example, the poetry of W. H. Auden and the plays of Samuel Beckett. First let’s look at Auden’s “The More Loving One”:

H. W. Auden (b. 1907 d. 1973)

Looking up at the stars, I know quite well

That, for all they care, I can go to hell,

But on earth indifference is the least

We have to dread from man or beast.

How should we like it were stars to burn

With a passion for us we could not return?

If equal affection cannot be,

Let the more loving one be me.

Admirer as I think I am

Of stars that do not give a damn,

I cannot, now I see them, say

I missed one terribly all day.

Were all stars to disappear or die,

I should learn to look at an empty sky

And feel its total dark sublime,

Though this might take me a little time.

There is little innovation in Auden’s poem—and nothing really innovative about Auden’s work as a whole, except his use of contemporary vocabulary and addressing contemporary themes—which is a basic requirement to be published in any literary journal in the English-speaking world, ironic purposes excepted.

Now consider Beckett, who was a year younger than Auden but outlived him by sixteen years. This is a sample of his most well-known play, “Waiting for Godot”:

VLADIMIR:

When I think of it…all these years…but for me…where would you be…(Decisively.) You’d be doing nothing more than a little heap of bones at the present minute, no doubt about it.

ESTRAGON:

And what of it?

VLADIMIR:

(gloomily). It’s too much for one man. (Pause. Cheerfully.) On the other hand what’s the good of losing heart now, that’s what I say. We should have thought of it a million years ago, in the nineties.

ESTRAGON:

Ah stop blathering and help me off with this bloody thing.

VLADIMIR:

Hand in hand from the top of the Eiffel Tower, among the first. We were respectable in those days. Now it’s too late. They wouldn’t even let us up. (Estragon tears at his boot.) What are you doing?

ESTRAGON:

Taking off my boot. Did that never happen to you?

VLADIMIR:

Boots must be taken off every day, I’m tired of telling you that. Why don’t you listen to me?

ESTRAGON:

(feebly). Help me!

VLADIMIR:

It hurts?

ESTRAGON:

(angrily). Hurts! He wants to know if it hurts!

VLADIMIR:

(angrily). No one ever suffers but you. I don’t count. I’d like to hear what you’d say if you had what I have.

ESTRAGON:

It hurts?

VLADIMIR:

(angrily). Hurts! He wants to know if it hurts!

ESTRAGON:

(pointing). You might button up all the same.

VLADIMIR:

(stooping). True. (He buttons up his fly.) Never neglect the little things of life.

As far as its writing and content are concerned “Waiting for Godot” is about as conventional as “The More Loving One” is innovative, and yet both Auden and Beckett are pillars of 20th century literature, the acclaim of one not resolutely greater than the other’s. Most basically we can assume that great innovation is not a prerequisite for great literature.

Beckett and the more innovate or experimental writers frequently do secure their place among the Great Books as well as the more tempered and conventional writers who master the ‘givens’ of prose and poetry and use only the material they have inherited from previous generations of writers. One might see parallels in questions of statesmanship: just as national leaders may be revered for their valour in wartime and others their benevolent and constructive use of times of peace. Is a Classicist, then, a pioneering innovator, or a master of the conventional?

Consider W. B. Yeats, a philosophical traditionalist and self-described Romantic who can hardly be aligned with the Victorian restraint of his early contemporaries who comprised his early contemporaries, given his sexual and occult obsessions. Nevertheless, his poetry is strongly rooted in the national traditions of both Ireland and all of Western Europe. Yeats is also a master of lyricism and formalism—a master of the conventional. Eliot (again), a self-described classicist, was also a remarkable innovator, the veritable father of English language free-verse and of High Modernism. Eliot’s work is also fundamentally rooted in the values and conflict of Western Europe, though his form is not so traditional.

In search of Classicism, we might ask ourselves what exactly separates or joins a Beckett and a Yeats or a Beckett and an Eliot. What makes sense to me is to distinguish between an experimental and a sustainable literary movement.

In search of Classicism, we might ask ourselves what exactly separates or joins a Beckett and a Yeats or a Beckett and an Eliot. What makes sense to me is to distinguish between an experimental and a sustainable literary movement.

Beckett’s obsessive minimalism, a direct reaction to Joyce’s stylistic decadence, was a ‘one-shot deal’. Not only is he credited with bringing the Modernist period to a close, but like a Napoleon Bonaparte, he built a magnificent empire in the Theatre of the Absurd and left his successors nothing to build on. Beckett was the first and last of his kind. Any attempt to ‘inherit’ Beckett would result in a second-rate imitation. That isn’t to say any and all influence Beckett impresses on a playwright or novelist is harmful, only that as a writer he was so unique in both form and content that one cannot say he leaves much to be said. Beckett was a nineteenth-century Modernist building a nineteenth-century literary empire in a nineteenth-century style and with nineteenth-century themes. (This isn’t at all a swipe at Beckett; the different roles played by Avant-Gardists and Classicists will be discussed later.) The same is not the case with, say, a W. B. Yeats or a James Joyce, both of whom still impress massive influence on poets and writers across the English-speaking world and especially in Ireland. The same cannot really be said for Beckett; where Absurdists still exist, their work is obscene or confounded to the point of being unpalatable to the common tongue. An Avant-Gardist earns their place in history by being dynamically creative and going against the grain of literary history, but it is impossible to create a sustained Avant-Garde movement. That would require multiple generations within the same nation with sustained popular support—essentially, a tradition of the Avant-Garde, which is a contradiction in terms.

VII. Why we need Classicists today

It makes sense that our contemporary writers wish to be Avant-Gardists: the modern world glorifies novelty for its own sake and will have nothing to do with Western Civilization pre-1960s. Believing the modern world began some half a century ago, and not wanting to thrust their noses into the primordial ash of whatever Pompeii stood there before, they cannot conceive of any tradition to draw upon. A few of them might admire Jane Austen, believing that any literate woman in the 1800s must have been a model feminist, but for the most part they are far too progressive to read Bunting, Browning, or Belloc. So they set about trying to reinvent the wheel.

The disappearance of Classicists has had an appalling impact on Western culture. Contemporary art has been relegated to a position where it does not inspire emotion or thought, only a Ph.D. thesis for the elites—and cringe of discomfort in the plebs—of literary society. Those who claim to tear down the barriers erected by traditional Western Civilization have made literature more inaccessible than it has ever been. As Roger Scruton points out in his documentary Why Beauty Matters:

The art of today shows us the world as it is: the here and now, and all its imperfections. But is the result really art? Surely something is not a work of art just because it offers a slice of reality, ugliness included, and calls itself art. (12:08-12:27)4

Postmodernists have decided that art has no fixed qualities—not naturalism or transcendence, beauty or ugliness, commonness or sublimity; therefore, everything can be art. The problem of course is that there’s a horrible popular reaction against this kind of thinking because people do intrinsically believe in transcendence, beauty, and sublimity. We experience those sensations almost daily, and those days where they are beyond our grasp are so gruelling and depressing. Do modern writers know this? In another essay Scruton goes on to explain that, yes, they do know this is all a lie, but they choose to lie to themselves about human nature—about art—and promise us, their audience an illusorily glimpse of our own progressive genius if we join them in their lie.

Faking depends on a measure of complicity between the perpetrator and the victim, who together conspire to believe what they don’t believe and to feel what they are incapable of feeling. There are fake beliefs, fake opinions, fake kinds of expertise. There is also fake emotion, which comes about when people debase the forms and the language in which true feeling can take root, so that they are no longer fully aware of the difference between the true and the false. Kitsch is one very important example of this. The kitsch work of art is not a response to the real world, but a fabrication designed to replace it. Yet both producer and consumer conspire to persuade each other that what they feel in and through the kitsch work of art is something deep, important and real.5

Roger Scruton

Poetry was once an art that few could master and all could enjoy; now, poetry is an art that all can master and none can enjoy. What we’re left with is an apoetic society. (Others would say a ‘prosaic’ society, but that undermines the beauty of prose. A mythical land where everyone read Hermann Hesse, Ivan Turgenev and Aldous Huxley would be infinitely more beautiful than our own.)

The point has been made—and made more deftly than I could attempt—that human beings do indeed hunger for beauty, truth, goodness, and other glimpses of a higher realm. For the average man or woman, this is the ultimate redundancy; only the Post-Modernist seems to have trouble grasping the concept.

There’s an impulse among many of Classicist sympathies to reject any attempt to enter into the world of modern culture even with the best intentions; they’ll claim an ardent love of and fascination with the Greeks and Romans, the Medievals and Renaissancians, the Romantics and the Victorians. They believe, and I’m sure sincerely, that modern art is a lost cause, that any attempt to foray into modern poetry will be a waste of time and effort. They relegate culture to the past like a beautiful bird long extinct, and when they see at a great old painting or watch a great old opera they conceive of a remarkable fossil rather than a living organism. This sort of thinking is extremely dangerous.

If we take Eliot’s definition of a ‘classic seriously, we see another reflection from Scruton highlighting the grave necessity of a living tradition of Classicism:

A high culture [which is analogous to a civilization’s body of classics] is the self-consciousness of a society. It contains the works of art, literature, scholarship and philosophy that establish a shared frame of reference among educated people. High culture is a precarious achievement, and endures only if it is underpinned by a sense of tradition, and by a broad endorsement of the surrounding social norms.6

We cannot do without our self-consciousness as a society. Civilization will not survive if we observe it behind plated glass. Unless our modern artists engage directly with our ancestors, our contemporaries, and even with our progeny, culture will stall in its tracks. Modern art that celebrates anarchism, Marxism, feminism sexual and racial minorities—none it affirms the artists’ countrymen or their conscience as a whole.

There is a rather oppressive expectation that gay or black or female writers can and must only write about issues pertaining to their own place in society, as though they could never count themselves as part of society as a whole. This modern, ‘progressive’ concept of art alienates so-called minority artists from Western Civilization and their own Nation more than any conservative force ever could: it is a call to self-marginalisation. Again, marginality this is seen as a positive, and neoterism is the greatest inherent good.

But consider how some gay writers—in Australia, for example, Patrick White and David Malouf—have defiantly refused to hyper-sexualize their work, refused to designate themselves as a voice only for those whose sexuality they share. When Malouf writes about homosexuality in his epic novel Ransom (set during the Trojan War) it is not to glorify his own sexuality or antagonize conservative heterosexuals, but rather to serve as a deeper philosophical perspective that is lost in Homer’s Iliad concerning the grief of Achilles over the death of Patroclus. Malouf does not treat his ideas about sexuality as a cause for himself to champion, an innovation, or a rupture in the continuity of the West. Rather, he portrays love as love, as it should be, and as it has existed throughout time; his novel is not a political stump but simply a work of art, and if one happens to disagree with his views on sexuality the beauty of the work is not at all lost. Our crowd of Modern Artists, however, do not accept Malouf’s temperament, and insist on banging their heads against the wall of public opinion, as though restating ideas that are at present heterodox will somehow become acceptable with no justification—rational or aesthetic—whatever. They treat their own views as unjustifiable lies and invite modern audiences to join them in indulging those lies. Needless to say, this strategy has failed miserably. Conversely, the success of Patrick White and David Malouf is unquestionable.

VIII. Final thoughts

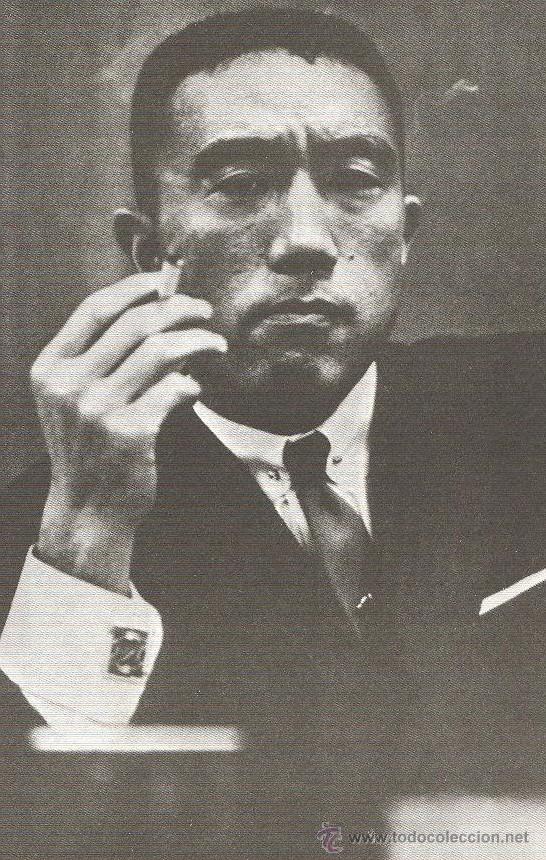

Yukio Mishima (b. 1925 d. 1970)

If Classicism comes across as an uneasy mixture of elitism and populism, that’s because it is. As Yukio Mishima said, “The highest point at which human life and art meet is in the ordinary. To look down on the ordinary is to despise what you can’t have.” Every man is not an artist, but the artist is an everyman. Yeats likened the poet to an alchemist, changing the raw elements of the earth into gold. But his poetry also celebrates those raw elements: the earth, the flesh, the heart, the soul. The worth of poetry is that it is all of these common and sacred things combined, as if by magic, into something unlike any one of them individually. There must be a certain humility in this perspective: the poet is not a lonely, tortured genius conceiving revolutionary works ex nihilo. The farmer, the artisan, the doctor, the machinist, the politician, the philosopher, the soldier, the priest: the poet is one of them, and all of them are countrymen to the poet. The Classicist celebrates this fraternity and strives to do right by his brothers and sisters. He is the keeper of their forefathers’ truth, beauty, and wisdom; when they ask, he offers what he knows; when they’re stubborn, he forces them to see what is right, even at his own peril. We see from history that the Classicist isn’t always the friendliest or the most pleasant character, but nonetheless he faithfully executes his mysterious duty—if not for the love of his fellow man, than for love of what they once were, and for what they might be once more.

IX. Short list of modern and contemporary Classicists and their nationality

-

-

- John Updike, American

- Jorge Luis Borges, Argentinian

- Liam Guilar, Australian

- David Malouf, Australian

- Les Murray, Australian

- Robertson Davies, Canadian

- Hugh Kenner, Canadian

- Simon Van Booy, British

- Salman Rushdie, British/Indian

- V.S. Naipaul, British/Trinidadian

- Rabindranath Tagore, Indian

- Seamus Heaney, Irish

- Frank McCourt, Irish

- Yukio Mishma, Japanse

- Edward Said, Palestinian

- Roy Campbell, South African

- J. M. Coetzee, South African

- Arturo Perez Reverte, Spanish

-

– M. W. Davis

The author is an American-born writer currently studying at the University of Sydney. He is an executive in the Australian Monarchist League—Sydney and Young Monarchists branch, the American Monarchist Association, and the Royalist Party USA. His personal blog is “The American High Tory”.

Endnotes

- T. S. Eliot, “What Is a Classic?” in Frank Kermode (ed.) Selected Prose of T.S. Eliot (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975) pp 115-131.

- Christina Stead, “Why I Left” The Independent Monthly (December 1994/January 1995) pp 42-43.

- Czesław Miłosz (Jane Zielonko, trn.) The Captive Mind (Secker & Warburg, 1953) pp vii-xiv.

- Roger Scruton (wtr. prod.), Why Beauty Matters (B.B.C., 2009).

- Roger Scruton, “The Great Swindle” Aeon (17 December 2012) (accessed, 8 October 2013)

- Ibid.

Leave a comment