Where is the one who is wise? Where is the scribe?

Where is the debater of this age? [Where is the Great Man?]

(1 Corinthians 1:20, English Standard Version)

Many theories have been postulated about what makes a person a leader, and from where leaders arise. The literature on this topic covers a broad range of paradigms and a large amount of amassed data on leadership qualities. The purpose of this essay is to focus on the controversy resulting from the ‘Great Man Theory of History’, which was an essential Victorian description of “the stuff” of leadership (Carlyle, 1840 p. 43). Three main themes emerge from the literature surrounding this controversy:

(1) the extent to which the great man influences social progress;

(2) the nature of greatness; and

(3) the great man’s role in shaping history.

The literature is diverse. It ranges from treaties on history to peer reviewed research papers and includes beginner readers on sociology, political manifestos, works of philosophy and other essays. Sometimes authors approach the notion of the ‘great man’ directly, and sometimes indirectly. They emerge from polarised schools of thought – some arguing from a conservative traditionalist disposition and others who were stalwarts of progressive modernity. As such this paper will explain the context of the controversy and then focus on following the controversy of the ‘Great Man Theory’ from the 19th and 20th Century. It will conclude with some contemporary observations and implications of the findings.

The Historical Context of Carlyle’s ‘Great Man Theory’

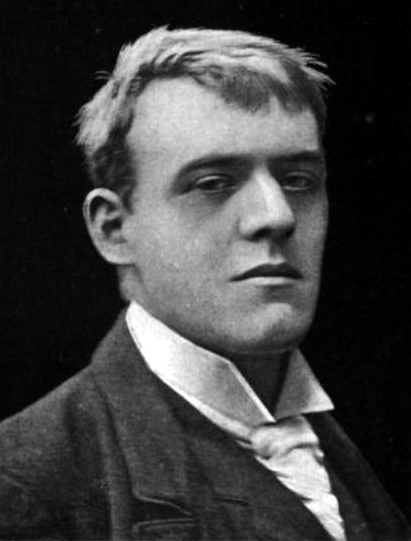

Hilaire Belloc (b. 1870 d. 1953)

In England at the beginning of the 19th Century an old, dwindling, conservative aristocracy were confronted by the existential threat of a powerfully emerging capitalist oligarchy. This new capitalist minority consisted of determined and ambitious merchants and industrialists (Belloc, 1913, p. 92-94). Their power had arisen after the Protestant Reformation and the dissolution of the monasteries resulting in the subsequent dispossession and appropriation of Catholic land by a small minority of Protestant gentry. This process of dispossession and appropriation lead to rapid urbanisation, which meant cheaply available labour for the industrialists in manufacturing towns. England was now “established upon a proletarian basis … [with] rich men possessed of the means of production on the one hand, and a majority dispossessed on the other” (ibid. p. 85). A reform driven group of Whig politicians agitated for further enfranchisement of the capitalist class and for binding of the remaining royal, and aristocratic power. These reformers, of whom Lord Thomas Macaulay was a leading light, quickened aristocratic intellectuals towards publishing a number of prophetical critiques and literary based warnings about the dangers of progress and social change. These texts came to be known as the ‘Sage Writings’ (Holloway, 1953, p. 22).

The conservative Thomas Carlyle, a bad tempered absolute monarchist and a critic of material progress, is credited with the provocative notion of the Great Man Theory (Goldberg, 1989, p.118). This is outlined in the opening pages of his sage text, On Heroes and Hero Worship:

“Universal History…of what man has accomplished … [is] but the History of the Great Men … sent into the world: the soul of the whole world’s history, it may justly be considered, were the history of these.” (1840, pp. 1-2; emphasis added)

Within this text the “Great Men” were heroic history shapers, who were “sent” and empowered by divine inspiration for the good of society. His examples included the ‘Hero’ as: ‘Divinity’ (Odin), ‘Prophet’ (Muhammad), ‘Poet’ (Dante, Shakespeare), Hero as ‘Priest’ (Luther, Knox), ‘Man of Letters’ (Johnson, Rousseau, Burns) and as ‘King’ (Cromwell, Napoléon). All of these great men rose humanity to a new plane of progress.

Carlyle recommended that people looking for leadership inspiration could examine the biographies of these greats. This text articulated popular sentiments of the Zeitgeist and would go on to influence countless historical biographies, almanacs, encyclopaedias and school curricula.

The Extent to which the Great Man Influences Social Progress

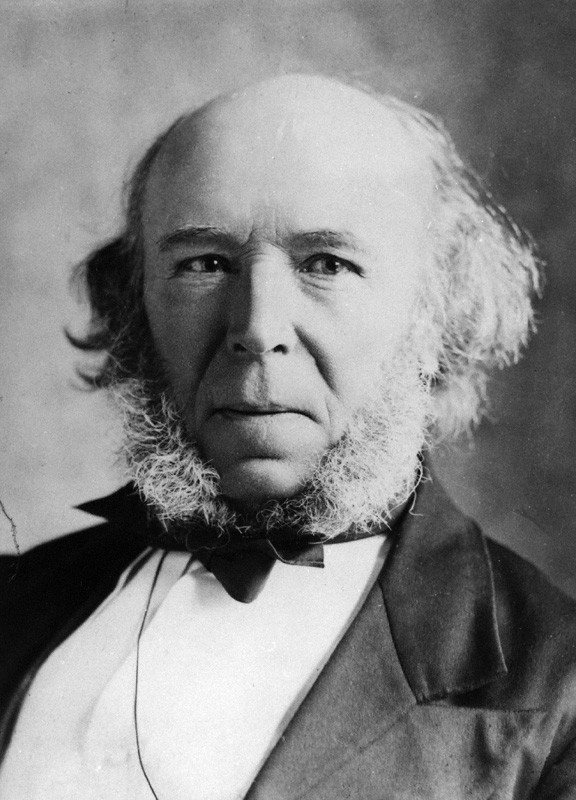

Baron Macaulay (b. 1800 d. 1859)

Heros and Hero Worship could be understood as a response to one of Carlyle’s intellectual adversaries, Lord Macaulay the Whig politician and historian. To Carlyle, Hero-worship was a profound social and religious truth; to Macaulay it was a sure sign of weakness of intellect (Goldberg, 1989, p. 118). Macaulay explained the “topoi” (time and place of the individual) as the reason for a great man’s supposed influence on human progress, in an essay on the poet Dryden:

“It is the age that forms the man, not the man that forms the age … it is evident … that without Columbus, America would [still] have been discovered. Society indeed has its great men and its little men, as the earth has its mountains and its valleys.” (Macaulay, 1828, para. 2)

Eleven years after Carlyle’s book was published, Herbert Spencer, a pioneer of sociology and social evolutionist argued persuasively about the ‘scientific’ nature of human progress in The Study of Sociology (1873) echoing Macaulay he stated:

“[If the great man] could really ‘remake his society’, his society none the less must have previously made him … he is merely the ‘proximate initiator’ … a real explanation of such changes … must be sought [not in the great man himself], but in the aggregate of social conditions, out of which he and they have arisen.” (Spencer, 1873, cited in Mallock 1898, p.27-28; emphasis added)

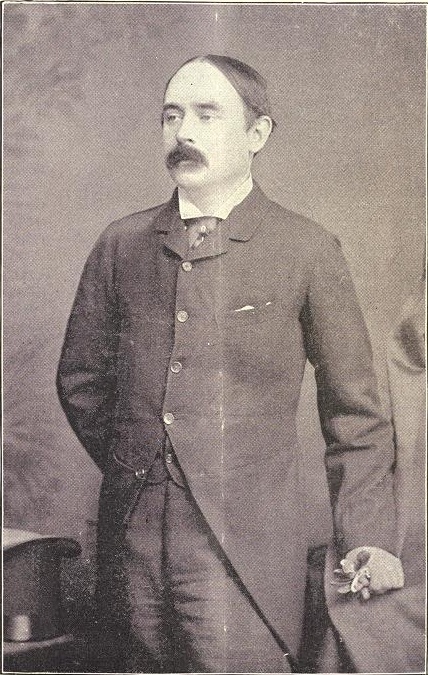

Herbert Spencer (b. 1820 d. 1903)

Spencer was attempting to counter Carlyle’s prevailing notion, and in doing so he was able to launch his own thesis on the progress of society (Mallock, 1873, p. 26). Spencer argued, rather than great men influencing society, a process of evolution shapes the “aggregate of social conditions”. For when the external environment changes, it causes changes in human behaviour, which in turn changes human institutions (social systems) in order for them to become consistent with new human behaviour – over time, all of this has become the “aggregate of social conditions” (Spencer,1873, p. 106, cited by Carneiro, 1981, p. 176).

Later in the century William Mallock, an apologist for conservatism and a member of the agrarian gentry (Cheek, 2012, para. 2), would write a defence of Carlyle against Spencer. Mallock’s own uncle had been friends with Carlyle and had written Carlyle’s biography. Mallock criticised Spencer for his failure to differentiate between the individuals and between the classes of men within the “aggregate of social conditions.” Mallock rightly identified the heart of the problem with attributing the “aggregate” as the source for the progress of society:

“The point of the issue is why, within the limits of the same industry, different men pursue it on different levels, some being masters and capitalists, some being labourers and subordinates.” (Mallock, 1898, p. 44)

Mallock continues:

“We must consider the individuals of each portion [of the aggregate] … and begin the inquiry [where] they begin it themselves: ‘Why am I … included in that portion of the aggregate which occupies an inferior position? And why are these men … more fortunate than I … included in the aggregate which occupies a superior position?’” (ibid, p. 46; emphasis added)

Mallock’s argument was that the social problems of his day (political agitation of the proletariat and the unequal distribution of wealth) “arose out of a conflict between different parts of the same aggregate” (ibid. p. 42); therefore the phenomena of the aggregate would not help grapple with any social problems. For Mallock it was obvious that even within the one aggregate substantial inequality existed between individuals and this was due to a naturally occurring hierarchy, which Spencer’s sociology ignored (ibid, p. 43). Mallock gives three reasons for these inequalities of position and then questioned whether or not these inequalities could be changed (ibid. pp. 46-48):

(1) External circumstances outside of the control of the individual;

(2) Exceptional individuals; and

(3) The homes of exceptional individuals, where opportunities to rise above the aggregate are cultivated for the progeny of the exceptional individual.

William Mallock (b. 1849 d. 1923)

His conclusion was that parliamentary legislation could help to relieve the first of these reasons, but that the remaining two reasons have to do with “congenital” talent, that is, talent from birth or from the advantages secured by birth into exceptional families (ibid. p. 53). Furthermore, in relation to the extent of the great man’s influence on social progress, Spencer and some other notables of his day claimed that the great man was merely the “proximate initiator” and not the cause of social progress; “often the same discovery is made by several men at once” they argued (Spencer, Kidd, Bellamy & Webb, cited by Mallock, 1898, p. 66). His counter-argument is that “[s]imultaneous discovery only shows that several men, instead of one, are greater than others.” (ibid. p. 67). Another argument that saw the great man as a mere proximate initiator was that “the difference between the great and ordinary man is slight” (Macaulay, Spencer, Kidd, Bellamy & Webb, cited by Mallock, ibid. p. 66). Mallock answered this by subverting one of Macaulay’s (1828) own illustrations from the physical world: like the differences on the surface of the earth are considered to be slight when astronomers calculate the revolutions of the earth, yet for the geographer or engineer the differences between the earth’s surfaces could be immense, so for the philosopher of sociology, the difference between the great man and the average man appears slight, yet for the average man affected by the works of great man – it is immense (Mallock, ibid. pp. 69 -70). Mallock’s clearest critique of Macaulay & Spencer et. al. runs as follows:

“Shakespeare’s contemporaries had the same national antecedents the he had; but they could not do what he did.” (ibid, pp.75-76)

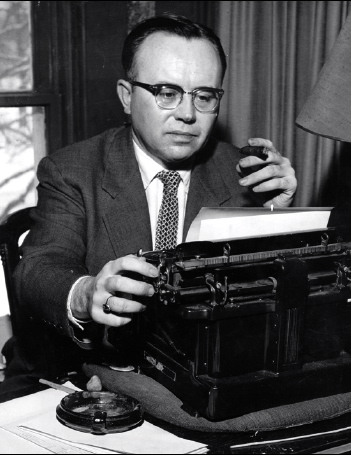

Russell Kirk (b. 1918 d. 1994)

Poetry, music and the arts are perhaps the most important examples that counter the “social aggregate” theory, because they are deeply unique, original and personal examples of superiority. Even the materialist Macaulay realised this – “In this respect, the works of Shakspeare, in particular, are miracles of art.” [Emphasis added] (1828, para. 31). Finally Mallock catches Spencer out as an intellectual hypocrite, when Spencer refers to Napoleon’s “immense ability” and for crediting Sir H. Bessemer with improvements to steal manufacturing (Spencer, cited in Mallock, ibid. pp. 85-87). Mallock even had the gall to assert that Spencer himself is a proponent of the ‘Great Man Theory’:

“[Spencer] divides the human race into the clever, the ordinary and the stupid … therefore progress must be due to the clever…who are the scattered few … and here we have in Mr. Spencer’s own language … the great man theory developed. That progress is due not to mankind at large, but to a minority of exceptional individuals.” (p. 114)

It is important to note that Mallock was not uncritical of Carlyle either, for he would then comment:

“Mr Spencer has assisted us [bringing the theory] into actual accordance with the facts of social life, and, unlike the wild exaggerations of Carlyle, it will be found to accord the more closely with them the more fully it is analysed. The error of writers like Carlyle was that they took the part for the whole. They recognised no great men at all except great men of the greatest kind – the heroic kind which appeared once or twice in a century.” (p. 116; emphasis added)

This brings us to the crescendo of Mallocks thesis:

“Whatever is done by great men of the heroic type, something similar, if not so striking, is done by a number of lesser great men also; that whilst the action of the heroic great men is intermittent, the action of the lesser great men is constant; and that the latter, as a body, although not individually, do incalculably more to promote progress than the former.” (p. 116)

The Nature of Greatness

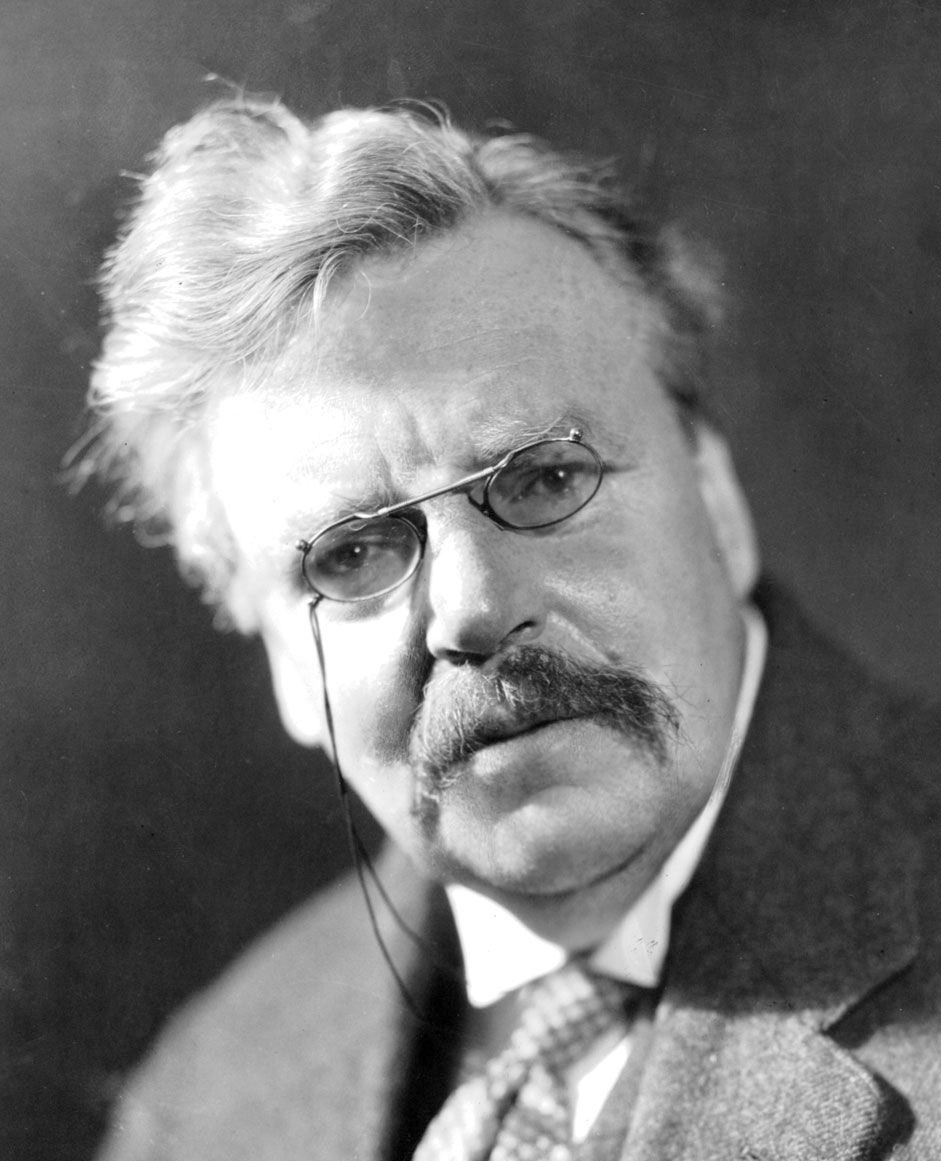

G. K. Chesterton (b. 1874 d. 1936)

We will now turn to the notion of greatness itself. Mallock’s thesis on greatness foreshadows much of the future ‘contingency’ theories of leadership. “Greatness, as an agent of social progress is in most cases not a single quality, but a peculiar combination of many.” These great men are “[f]or the most part great in relation to special results only … [these results] are great to varying degrees and many of them in other relations may be ordinary. It must be understood that greatness is not an absolute thing.” (Mallock, 1898, p. 127; emphasis added). For Mallock, greatness was contingent on the situation. The great qualities that might get a person great results in one situation may leave them totally insufficient in another.

Let us return to Carlyle, who perceived that rather than being contingent on the situation, greatness was an all-round characteristic. He admonishes his readers to find the all-round “Ableman” and follow him as the absolute sovereign:

“Find in any country the Ablest Man that exists there; raise him to the supreme place, and loyally reverence him: you have a perfect government for that country … It is in the perfect state; an ideal country.

“The Ablest Man; he means also the truest-hearted, justest, the Noblest Man: what he tells us to do must be precisely the wisest, fittest, that we could anywhere or anyhow learn; — the thing which it will in all ways behove us, with right loyal thankfulness, and nothing doubting, to do!” (Carlyle, 1840, pp. 218-219; emphasis added)

While Russell Kirk (1953, p. 243) calls the above notion a “disastrous delusion”, G. K. Chesterton provides us with a gentler critique of Carlyle’s ‘great man’ which may sweeten some of Carlyle’s critics:

“The notion that Carlyle’s theory of hero worship was a theory of terrified submission to stern and arrogant men [is wrong] … He admired great men primarily … because he thought that they were more human than other men.” (Chesterton, 1902, para. 9; emphasis added)

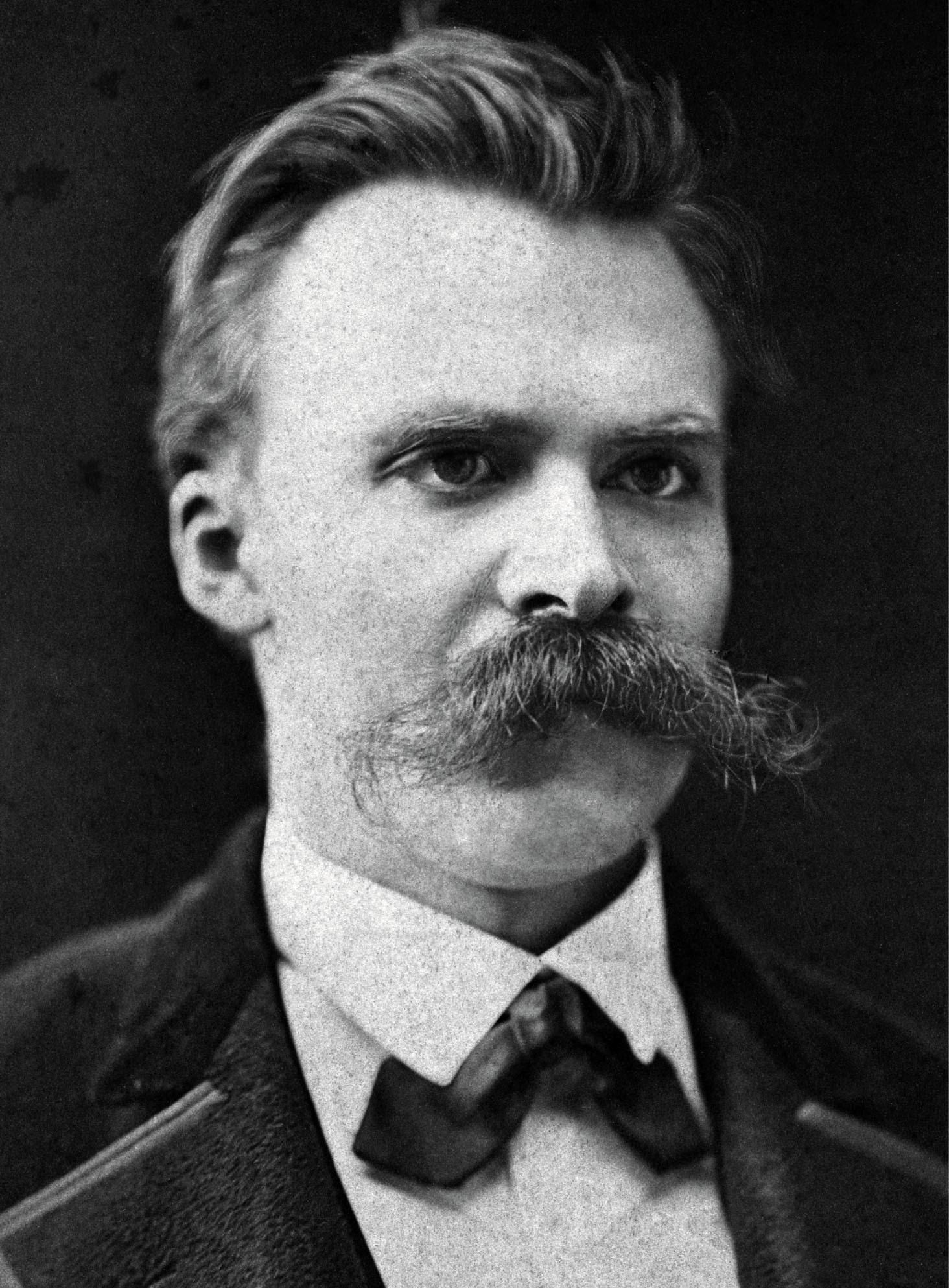

Friedrich Nietzsche (b. 1844 d. 1900)

If Carlyle’s ‘great man’ was “more human”, was he to be an all round superhuman? In the same century, philosophical literature from the European continent such as Friedrich Nietzsche’s “Übermensch” (Superman) from his text Thus Spoke Zarathustra (Nietzsche, 1885; Breazeale, 1997) and Søren Kierkgaard’s “Knight of Faith” from his text Fear and Trembling (Kierkgaard, 1843 cited in Evans & Walsh, 2006) may both share a resemblance with Carlyle’s great man, for they are superior, effective and not restrained by the common. They expect the impossible and have faith for the here and now – with “will to power”, or through “great faith” they achieve greatness and effect social progress.

Matthew Arnold can shed more sweetness and light upon this question. His writings can be seen as both modelled on Carlyle and, at times, in reaction to Carlyle (Starzyk, 1970). In his work Culture and Anarchy, while wishing to reprove progressive materialists in his day, he wrote about greatness in the following way:

“Everyone must have observed … late discussions as to the possible failure of our supplies of coal. Our coal, thousands of people were saying, is the real basis of our national greatness; if our coal runs short, there is an end of the greatness of England. But what is greatness? ... Greatness is a spiritual condition worthy to excite love, interest, and admiration; and the outward proof of possessing greatness is that we excite love, interest, and admiration. If England were swallowed up by the sea to-morrow, which of the [two], a hundred years hence, would most excite the love, interest, and admiration of mankind … the England of the last 20 years [1829-1869] or the England of Elizabeth, of a time of splendid spiritual effort, but when our coal, and our industrial operations depending on coal, were very little developed? Well then, what an unsound habit of mind it must be, which makes us talk of things like coal ore iron as constituting the greatness of England.” (1869, p. 43; emphasis added)

Matthew Arnold (b. 1822 d. 1888)

Arnold’s notion of “greatness” is a spiritual reality – he maintained that while not being perfectible in any utopian sense, humans should strive to become perfect by developing the fullness of their humanity. This was to be done not merely through “science”, “machinery” or “light” (Ibid. p.44), what Joseph Conrad symbolised as the “torch of progress” in the Heart of Darkness (1899), but through “sweetness” – culture, aesthetics and the pursuit of the ideal and the great. Greatness is then the possession and continuation of the good, the beautiful and the true – both sweetness and light. Thus ‘great men’ – to allow both Arnold and Chesterton to improve Carlyle – are not Nietzschien ‘supermen’ beyond good and evil, to whom a people submit out of terror, but rather they are more perfect men, whom excite in a people an affection and admiration. They are the best of men – morally, spiritually, culturally and intellectually.

The Great Man’s Role in Shaping History

Carlyle’s 1840 text, dripping with sentiment that is characteristic of German Romanticism, sought to bolster a belief in a divine or spiritual right of the aristocracy – a society ruled by the excellent, or the ‘Able-man’ (ibid. p. 217). Carlyle was no enthusiast of the reform acts of parliament, and had argued for all the power of state to be with the Monarch (Kirk, 1953, p. 5), therefore his understanding of history centred on the ‘great man’ and divine purpose. Spencer, a political libertarian who held an “anti-aristocratic bias” (Francis, 2007, p. 247), ardently disputed the historical importance of great men in his book Social Statics (1851, p. 433):

“Those who regard the histories of societies as the histories of their great men, and think that these great men shape the fates of their societies, overlook the truth that such great men are the products of their societies.”

When talking about the nature of history in his essay What Knowledge is of Most Worth? (1884) Spencer could say:

“Only [recently] have historians [given] us … truly valuable information. As in past ages the king was everything and the people nothing; in past history, the doings of the king fill the entire picture … [now] the welfare of nations rather than of rulers is becoming the dominant idea … historians [are] beginning to occupy themselves with the phenomena of social progress. The thing it really concerns us to know is the natural history of society.” (p. 29-30; emphasis added)

Spencer’s take on history was that it demonstrated the march of progress and could be formulated through scientific method, enabling general inferences to be made and for overarching laws to be devised. However Spencer had permitted that great men were important, but limited to “the history of primitive societies… [where] the great leader [was] all-important [in] endeavours to destroy one another” (cited in Mallock, 1873, p. 56). Mallock latched onto this admission and extrapolated the reasons of the great man’s success in primitive war to industrial peace-time:

“How does a great man fulfill his function in war? By ordering others.

“Such a leader leads, because of [his] superior qualities … He supplies the fighting men an intelligence not their own – often with courage, a presence of mind, and a resolution. He dictates to them … the direction … the manner … [and] the movements.” (Mallock, 1873, p. 58)

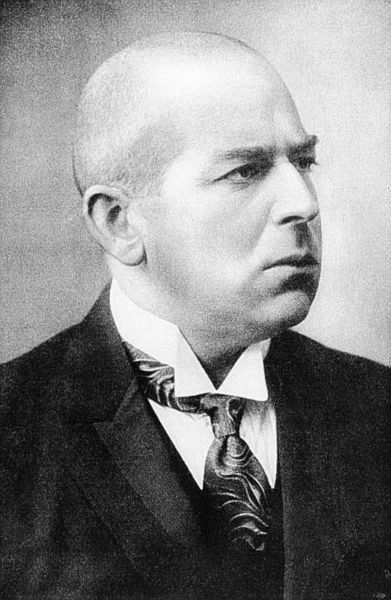

Oswald Spengler (b. 1880 d. 1936)

He goes on to explain, that “the great man, in peace, does precisely the same thing…the great man of business orders his employees” (ibid. pp. 59-61). In doing so, Mallock argued for a view of history that is shaped by a large number of ordinary leaders rather then the few great heroes.

La Monte (1907) identified this in his ideologically driven Socialism: Positive and Negative. In which heargued for a Marxian materialistic conception of history based on “the economic factor [being] the dominant, determining factor in every day human life” La Monte labelled Mallock a “servile literary apologist of capitalism” (La Monte, 1907, p. 17) implying that Mallock’s ordinary leaders were the capitalist class. For La Monte, Socialism was a “scientific prediction” that would serve, as an “ideal” for human society to work towards, much like Carlyle’s conception of the great man.

On the nature of history, Oswald Spengler a German historian and champion of elitism and high culture would argue in The Decline of the West (1918), that rather than driving towards progress, human societies have a “definite duration” and are cyclical in nature, rising, maturing then falling (p. 36). Great men, or heroes must emerge out of historic necessity to aide the transition of a culture from one phase to another. The Western world is in the final phase and would capitulate because it had become materialistic:

“Power can be overthrown only by another power, not by a principle, and only one power that can confront money is left. Money is overthrown and abolished by blood. Life is alpha and omega … ever in history it is life and life only – race-quality, the triumph of the will-to-power … we have the freedom to do the necessary or to do nothing. And the task that historic necessity has set will be accomplished with the individual or against him.” (Spengler, trans. Knopf, 1965, p. 415; emphasis added)

For Spengler, Marx was a false prophet and “money” signified the materialism inherent in both dead capitalism and stillborn socialism, both leading to the end of a culture. It is the triumphant-individual, who by force (blood) can bring forth the birth of a new ‘culture’. Anachronistically, Macaulay’s views on the nature of history are most striking in contrast with Spengler’s:

“Those who compare the age on which their lot has fallen with a golden age which exists only in their imagination may talk of degeneracy and decay: but no man who is correctly informed as to the past will be disposed to take a morose or desponding view of the present.” [Emphasis added] (Macaulay, 1848, para. 3)

Macaulay was a product of the enlightenment, proudly materialistic and a champion of science and the torch human progress (Kirk, 1953, pp. 187-197). In fact his The History of England (1848) outlined that all history was directed towards human progress: “For the history of our country during the last hundred and sixty years is eminently the history of physical, of moral, and of intellectual improvement.” Compare this with Carlyle’s opening line – “Universal History … of what man has accomplished … [is] but the History of the Great Men … sent into the world” (1840, p. 1). It reads as if Macaulay were offering a direct challenge to Carlyle’s notion of the heroic in history’s progress.

Georg Hegel (b. 1770 d. 1831)

The German philosopher Hegel was a contemporary of Carlyle, who embraced a parallel view of the role of exceptional personalities in history in his Philosophy of History (1837). For Hegel, great people served as vehicles for the gradual “unfolding” of the God-Spirit, or Geist in the world. These individuals, may not be conscience that they are actors in a unfolding divine fatalistic drama for “they are men … who appear to draw the impulse of their life from themselves …” their actions “appear to be only their interest, and their work …[they] were practical, political men … thinking men” who had an insight into what was required at the time, what “was ripe for development” (Hegel, 1837, para. 33; emphasis added). Hegel went on to define exactly what makes a ‘great man’:

“World-historical men — the Heroes of an epoch — must, therefore, be recognised as it’s clear-sighted ones; their deeds, their words are the best of that time … for it was they who best understood affairs; from whom others learned, and approved, or at least acquiesced in their policy.” (ibid. emphasis added)

This makes Hegel’s great men contingent on the times, on matching the right man with the right epoch. Heroes, he wrote, are not agents who act independently; rather, they serve as agents for the inevitable Geist in moving history forward. (Hegel, 1837, cited in Renaud, 2011, Para. 9)

In his text, The Hero in History (1943), Sidney Hook opposed all forms of Hegelian determinism and argued that humans work an “event-making” role in constructing the future. Human progress is neither a historical necessity nor finished. For Hook this conviction was crucial. He argued that, when a society is at the crossroads of choosing the direction of further development, an individual can play a dramatic role and become the one on whom the choice of the historical pathway depends (Hook, 1943, p. 175)

Concluding Observations and Remarks

The literature surrounding the ‘Great Man Theory’ controversy has revealed three things:

(1) history can either be perceived as heading towards human progress or human decline;

(2) This is either occurring inevitably or it can be assisted or halted through the powers of an individual or by groups of people; and

(3) Greatness is non material, either contingent on the situation or, that in every situation a truly great man’s greatness will be demonstrated.

‘Saint John the Evangelist’ – oil on canvas by Bernardo Cavallino, circa 1641-43

Into the 21st Century, the ‘Great Man Theory’ has become an underpinning of management and leadership courses offered in many business schools and universities. During this time empirically driven research has emerged around the idea of ‘Trait Theory’, which is essentially ‘great man’ in nature (Hoffman, et. al. 2010) as is the ‘Charismatic’ Leader (Shils, 1965). Finally, some argue that the ‘great man’s’ dominance is intuitive and almost inevitable – a biological fact found within our DNA, such as Knipe & Maclay’s Dominant Man (1972) and Christakis, Dawes, De Neve, Fowler, & Mikhaylov’s twin study (2012). If greatness were truly part of our DNA, it would hold significant implications for a society driving towards all forms of equality. Would it not imply that attempts at equality are fighting against nature and the natural order? Will legislating for equality lead to tyranny – for equality loathes all forms of superiority and may endeavour to suppress it through technocratic means. Spengler argues that egalitarian measures inextricably lead to tyranny and mediocrity. For the opposite of equality is not inequality, but rather quality and in supressing quality, a culture descends into a base competition jostling for victimhood status. (Spengler, 1933, cited in Bertonneau, 2012). Perhaps, alternatively, the capitalist class will turn the ‘leadership gene’ into a commodity, engraining the materialism that continues to lead our culture into decay (Spengler, 1918). Would a great man arise for this epoch, and rescue us from such madness?

Examining the claims of Christianity may be the place to conclude the great man question. Concluding with Christianity is paradoxical – it advocates entrusting oneself under the greatness of another, whom through his own ‘will to power’ gave up his life and in so doing, conquered death itself (Hebrews 2:14). It calls forth a master of heaven and earth who is both the Carlyle-Chesterton-Arnold ‘Able-man’ and the ancient ‘God-man’ – who becomes a brother, in flesh and blood (Hebrews 2:14), to sympathise with our pathos and elevate us to the throne room of God. If equality is a false god, and ‘great men’ are few and far between – then to have faith in Christ, is a realistic response to the natural order of greatness.

Saint John the Apostle had a vision that one day, this Christ would return to judge the nations and make war on his enemies. It is a startling picture that announces the end of all the ages (Revelation 19:11-21, English Standard Version):

11 Then I saw heaven opened, and behold, a white horse! The one sitting on it is called Faithful and True, and in righteousness he judges and makes war.12 His eyes are like a flame of fire, and on his head are many crowns, and he has a name written that no one knows but himself. 13 He is clothed in a robe dipped in blood, and the name by which he is called is The Word of God. 14 And the armies of heaven, arrayed in fine linen, white and pure, were following him on white horses. 15 From his mouth comes a sharp sword with which to strike down the nations, and he will rule them with a rod of iron. He will tread the wine press of the fury of the wrath of God the Almighty. 16 On his robe and on his thigh he has a name written, King of kings and Lord of lords [Great Man of Great Men].

– Dewi Sant

The author, who publishes under this pseudonym, is a Religion and Visual Arts pedagogue in a prestigious Sydney boys school.

Bibliography:

- M. Arnold, Culture and Anarchy (Tredition Classics, 1869).

- H. Belloc, The Servile State (Liberty Fund, 1913).

- T. Bertonneau, “Oswald Spengler on Democracy, Equality, and ‘Historylessness’” The Brussels Journal (31 May 2012 @ 18:00) <www.brusselsjournal.com> (accessed 11 June 2013).

- D. Breazeale, Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy: Friedrich Nietzsche, Untimely Meditations (Cambridge University Press, 1997).

- T. Carlyle, On Heroes, Hero-Worship and the Heroic in History (Frederick A. Stokes & Brother, 1840).

- R. Carneiro, “Herbet Spencer as an Anthropologist” The Journal of Libertarian Studies 5:2 (Spring 1981).

- L. Cheek, “W. H. Mallock revisited” The Imaginative Conservative (3 January 2012) <www.theimaginativeconservative.org> (accessed 10 June 2013).

- G. K. Chesterton, Twelve Types (Arthur L. Humphreys, 1912).

- N. Christakis, C. Dawes, J. De Neve, J. Fowler, and S. Mikhaylov, “Born to Lead?: A Twin Design and Genetic Association Study of Leadership Role Occupancy” The Leadership Quarterly 24:1 (February 2013) [DOI: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.08.001].

- J. Conrad, The Heart of Darkness (Penguin, 1899).

- C. Evans, and S. Walsh, Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy: Søren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

- M. Francis, Herbert Spencer and the Invention of Modern Life (Cornell University Press, 2007).

- M. Goldberg, “‘Demigods and Philistines’: Macaulay and Carlyle, a Study of Contrasts” Studies in Scottish Literature 24:1 art. 11 (1989).

- G. Hegel, Lectures on the Philosophy of History (1837) (accessed online 11 June 2013).

- B. Hoffman, B. Lyons, R. Maldagen-Youngjohn, and D. Woehr, “Great Man or Great Myth?: A Quantitative Review of the Relationship Between Individual Differences and Leader Effectiveness” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 84:2 (June 2011) [DOI: 10.1348/096317909X485207].

- J. Holloway, The Victorian Sage: Studies in Argument (Macmillan, 1953).

- S. Hook, The Hero in History (Cosimo, 1943).

- R. Kirk, The Conservative Mind: From Burke to Eliot (Regency, 1953).

- H. Knipe, and G. Maclay, The Dominant Man: the Mystique of Personality and Prestige (Souvenir, 1972).

- R. La Monte, Socialism: Positive and Negative (Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1907).

- T. Macaulay, “Dryden” Edinburgh Review 47 (January 1828).

- T. Macaulay, The History of England from the Ascension of James the Second (Porter & Coates, 1848).

- W. Mallock, Aristocracy and Evolution: A Study of the Rights, the Origin, and the Social Functions of the Wealthier Classes (Adam and Charles Black, 1898).

- M. Renaud, “#55 iHeroes, ireligion and ihistory” The Naked Theologian (12 October 2011) <thenakedtheologian.com> (accessed 9 June 2013).

- E. Shils, “Charisma, order and status” American Sociological Review 30:2 (April 1965).

- H. Spencer, Social Statics (John Chapman, 1851).

- H. Spencer, The Study of Sociology (10th ed., C. Kegan Paul & Co., 1873).

- H. Spencer, What Knowledge is of Most Worth? (J. B. Alden, 1884).

- O. Spengler, The Decline of the West (Oxford University Press, 1918).

- L. J. Starzyk, “Arnold and Carlyle” Criticism 12:4 art. 3 (1970).

Reblogged this on Manticore Press.

See also at EXCERPTS FROM THE LATTER DAY PAMPHLETS: NO. IV