Map of Europe showing largest ethnic minority, by national flag, per country.

While European elites incrementally embrace the dystopic nightmare of Jean Raspail’s Camp of the Saints as the inevitable future of the continent, traditionalists of the Occidental ‘dissident-right’ can only look on with horror. Our political leaders, instead of addressing the root ideological causes of the crisis, pretend to treat it seriously only by accommodating the problem with seemingly unending concessions to an intolerable situation.

The only people who have stood against a vision of Europe cast into a tempest of chaos and the inevitable totalitarianism that will accompany it are those who have recently taken to the streets in defiance of their political overlord’s suicidal altruism – such as the protesters at last Saturday’s immigration restrictionist rally in Warsaw1 – or the other mostly Central European political leaders who are trying to buck the morbid and accelerating trend. Their reward? Isolation by their Western counterparts for an alleged lack of sufficient ‘compassion’ towards the invader.

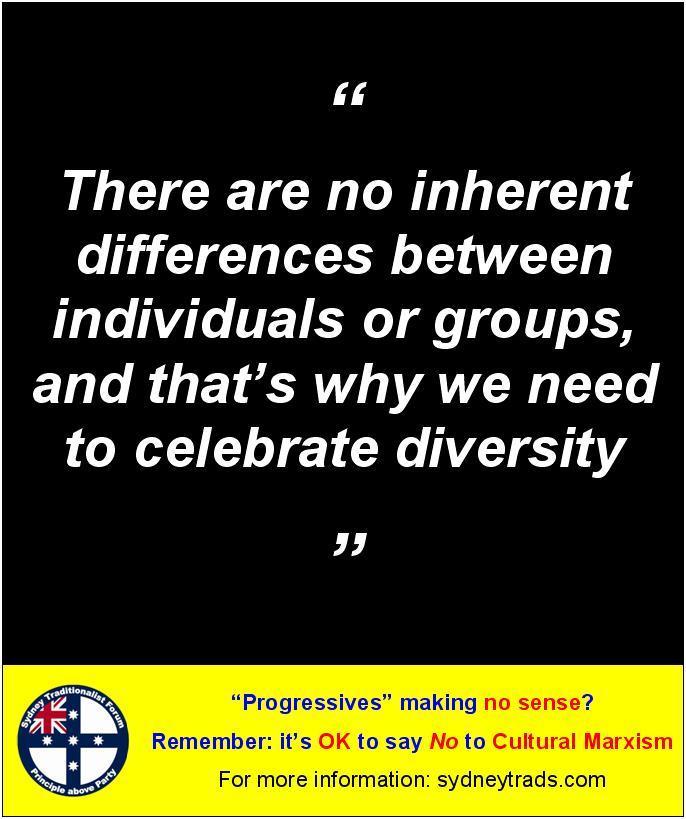

Be that as it may, behind the ideology which has facilitated the current crisis on Europe is the rejection of national particularism and the elevation of the clichéd mantra diversity is strength to the position of transnational quasi-religious doctrine. Indeed, on the occasion of the opening of the Ninth Session of the United Nations’ Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issued, the United Nations Secretary General, Ban Ki-Moon stated that “Diversity is strength – in cultures and in languages, just as it is in ecosystems.”2

Be that as it may, behind the ideology which has facilitated the current crisis on Europe is the rejection of national particularism and the elevation of the clichéd mantra diversity is strength to the position of transnational quasi-religious doctrine. Indeed, on the occasion of the opening of the Ninth Session of the United Nations’ Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issued, the United Nations Secretary General, Ban Ki-Moon stated that “Diversity is strength – in cultures and in languages, just as it is in ecosystems.”2

The question however is this: if His Excellency’s pronouncements are to be treated as a sincere expression of what he genuinely believes to be true, then why has South Korea, his homeland, not been more vociferous in offering to welcome the flood of Arabic speaking Muslim ‘refugees’ into its polis, like the United States or Australia have recently (and stupidly) done? Why has His Excellency not called on his country to express greater compassion to the allegedly so-desperate? According to the New World Encyclopaedia, Korean people are “the most homogenous people on Earth” and “for the most part Koreans have maintained their racial purity.”3 If diversity is strength, then Korea must therefore be one of the weakest societies on the planet, no? Thus, why does the UN Secretary General continue to deny his poor ethnically homogenous nation the enriching strength of the diversity that it so desperately needs?

The answer is of course rather obvious to those with eyes that see: the push to ‘enrich’ and ‘diversify’ societies is suspiciously focused on certain types of societies, i.e. those composed of, or settled by, Western European peoples; no other type of society seems to be under the same or similar pressures to accommodate the desperate escapees of the Third World. How many local Islamic and Arab states (which are not embroiled in wars or conflict, and which possess the financial resources to help their disenfranchised religious and ethnic brethren) have offered or been asked to take on the responsibility of assisting the ‘refugees’ currently flooding Europe? How many empty ‘ghost cities’ in China could be filled with these allegedly ‘enterprising’ and ‘enriching’ Arab and North African Muslims?

The answer is of course rather obvious to those with eyes that see: the push to ‘enrich’ and ‘diversify’ societies is suspiciously focused on certain types of societies, i.e. those composed of, or settled by, Western European peoples; no other type of society seems to be under the same or similar pressures to accommodate the desperate escapees of the Third World. How many local Islamic and Arab states (which are not embroiled in wars or conflict, and which possess the financial resources to help their disenfranchised religious and ethnic brethren) have offered or been asked to take on the responsibility of assisting the ‘refugees’ currently flooding Europe? How many empty ‘ghost cities’ in China could be filled with these allegedly ‘enterprising’ and ‘enriching’ Arab and North African Muslims?

Obviously, this diversity is strength nonsense is pushed only on the gullible, because only the gullible believe obvious nonsense to be true. No people with a healthy sense of self-respect and pride in its own unique identity would believe such a dangerously suicidal falsehood. Korean society is certainly not weak for being largely homogenous; such homogeneity can provide the social capital necessary for economic solidarity,4 and an argument could be made that such solidarity might have had a positive impact on Korea’s ability to weather the 2009 global financial crisis.5 The Koreans are no fools. Kyoung-Hee Moon of Changwon National University writes in the East Asia Forum that:

“The total number of foreign residents in Korea, the majority of whom are temporarily visiting migrants or students, accounts for only 2.2 per cent of the country’s total population. In addition, Chinese residents represent, at 57 per cent, the highest share of these foreign residents, and about half of these Chinese residents have Korean ancestry. Korean society is still largely ethnically homogeneous and racially distinctive, and the term ‘multiethnic Korea’ remains an unconvincing descriptor.”6

Victor Orbán, President of Hungary

So even the existing Korean ‘diversity’ – such as it is – is rather invisible by European or Anglosphere standards because most of the foreign workers are from poorer Asian countries. But even this has been problematic. A 21 October 2009 Amnesty International Report criticised the rising instances of racial discrimination in that country.7 This is because, as Kyoung-Hee Moon writes, to many Koreans their land “is a homogeneous nation that should maintain a strong ethnic national identity based on shared blood and ancestry.”8 The existence of foreign ethnic groups, albeit Asian, still has the potential to cause social discord and disharmony. Korean “multiculturalism” was therefore largely designed to assimilate the spouses of ethnic Koreans instead of engaging in the melting-pot social experiments of Western progressive obsessives.

Korean political society, far from embracing Western leftists’ favourite Orwellian slogans, has instead taken a blunt position in respect of illegals within its borders: “Crackdown and forced deportation is the government’s key policy to get rid of undocumented migrants, and 23 detention facilities have been set up nationwide.”9 Despite this, it is difficult to locate Western progressives’ denunciations of Korean ‘nativism’ comparable to what Victor Obán’s Hungary has had to weather in recent weeks. Although there is some evidence of changing social attitudes to ethnicity and citizenship in Korea, the consensus has not embraced the fashionable Western ethnomasochism of Frankfurt School derived Cultural Marxism. Choe Sang-Hun writes in the New York Times that:

“a recent forum to discuss proposed legislation against racial discrimination turned into a shouting match when several critics who had networked through the Internet showed up. They charged that such a law would only encourage even more migrant workers to come to South Korea, pushing native workers out of jobs and creating crime-infested slums. They also said it was too difficult to define what was racially or culturally offensive. ‘Our ethnic homogeneity is a blessing,’ said one of the critics, Lee Sung-bok, a bricklayer who said his job was threatened by migrant workers. ‘If they keep flooding in, who can guarantee our country won’t be torn apart by ethnic war as in Sri Lanka?’”10

Ban Ki Moon, General Secretary of the United Nations

Some academic authorities in Korea concede that the cultural fixation on racial purity has been a function of the peninsula’s turbulent history, particularly it Japanese occupation during the Second World War, and the concept of “racially homogeneity” is in fact “new and ideological.”11 Nevertheless, the Korean establishment is reluctant to do an about-face and assume the ‘subscription identity’ ideology so popular among bon hommes of the West. Kang Shin-Who writes in The Korea Times:

“The Ministry of Education, Science and Technology has no immediate plans to completely erase the term ‘homogeneous Korean people,’ thought it has toned down the parts emphasizing it. ‘It’s still a bit too early to remove the term homogenous people,’ said Min Byung-kwan, the ministry director in charge of textbooks.”12

What those pushing for more European states to take in more migrants from the Middle East and North Africa are effectively saying is diversity for you but not for me. One wonders though, if it’s such an obviously good thing, why would these activists on the enlightened and compassionate left be so generous in their alleged good-will towards the civilisation that their ideology is historically mobilised to undermine and eliminate.

There are those among the ‘alternative right’ who have suggested that anti-racism is coded rhetoric for an essentially anti-Western and anti-European ideology of hate. Given the obvious hypocrisies on display in recent weeks, it is difficult to deny that they may indeed have a point; denouncing those who question the underlying assumptions of the status quo as ‘extremists’ will surely lose its sting in the near future given that the incompetence, impotence and utter moral bankruptcy of the mainstream is becoming increasingly evident with each passing day.

– SydneyTrads Editors

Endnotes:

- Editorial, “Rally Protesting Forced Mass Third-World Immigration, Warsaw Poland” SydneyTrads – Weblog of the Sydney Traditionalist Forum (12 September 2015) <sydneytrads.com> (accessed 13 September 2015).

- Statement: Secretary General’s Remarks at Opening of the Ninth Session of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, New York, 19 April 2010 <un.org> (accessed 11 September 2015).

- “Demographics of South Korea” New World Encyclopaedia (undated, last modified 6 May 2015 at 17:07) <newworldencyclopedia.org> (accessed 11 September 2015).

- See generally: Pyong Gap Ming, Ethnic Solidarity for Economic Survival – Korean Greengrocers in New York City (Russel Sage Foundation, 2011).

- See generally: Gil Soon Han, Nouveau-riche Nationalism and Multiculturalism in Korea: A Media Narrative Analysis (Routledge, 2015).

- Kyoung-Hee Moon, “The challenge of becoming a ‘multiethnic Korea’ in the 21st Century” East Asia Forum (online) (18 March 2010) <eastasiaforum.org> (accessed 11 September 2015).

- Choe Sang-Hun, “South Korean Struggle with Race” New York Times (online) (1 November 2009) <nytimes.com> (accessed 11 September 2015).

- Kyoung-Hee Moon, op. cit.

- Ibid.

- Choe Sang-Hun, op. cit.

- Kang Shin-Who, “Is Korea Homogenous Country” The Korea Times (online) (22 December 2008) <koreatimes.co.kr> (accessed 11 September 2015).

- Ibid.

Leave a comment