In December 1817 the romantic poet, John Keats (1795-1821), wrote a letter to his two brothers, George and Thomas, where his now famous expression negative capability first appeared. Keats was returning home with his friends, Charles Wentworth Dilke and Charles Brown, when he and Dilke began to discuss what qualities go into forming a man of achievement.

Negative capability is a simple expression that saw the light of day in a personal letter. Yet the essence and mood of negative capability is essential to the perennial philosophy, or what the ancient Greek philosophers, especially the stoics, called the philosophy of life. Negative capability was not meant to carry the vacuous, Avant Garde connotation that many modish literary critics attribute to it today. The expression is the conclusion of an argument that spells out an exulted sentiment for life. Negative capability is the articulation of an intuition that Keats felt for his own existence: life understood from the inside out.

Gabriel Honoré Marcel

Negative capability is the opposite of the myopia that positivism demonstrates in negating the existence of a supreme being. By negative capability we should understand man’s capacity to allow ourselves to be dazzled by the ontological mystery of human existence. This attitude toward life brilliantly anticipates the purgation that hubris brings about to people whose lives are dominated by a nihilistic cul-de-sac. Negative capability is the opposite of nihilism because it signals a noble form of human existence that is inspired by the recognition of objective values.

Keats’ letter to his brothers expresses the poet’s displeasure with the scope of the scientific method, which he rejected. Keats reacted to the overreach of science and philosophical materialism, which in our own time has morphed into scientism, physicalism, biologism and many other forms of reductionism that destroy man’s capacity for self-reflection, and ultimately, the attainment of wisdom.

The idea that man should have a theory of everything was repulsive to Keats. He is vindicated in his belief, for we have enough historical knowledge and an abundance of data to understand the destructive implications of a theory of everything on man’s psyche in post-modernity. Today we have created an altar to glorify aberrations of untold stripes many a generation ago. It does not take much imagination and intelligence to realize that a theory of everything destroys the fabric of innocence and spontaneity. Man, the romantic poet suggests, exists as part of a grand totality of which man is a finite manifestation.

Rather than being intimidated by the cloak of not-knowing, Keats reasoned that ontological mystery fuels human history and makes life worth living and enjoyable. To make sense of our lack of knowledge – what Socrates called his ignorance – is itself a form of knowledge and wisdom.

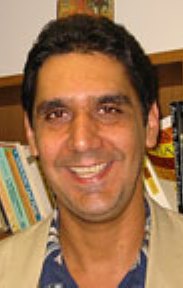

William Blake by Thomas Phillips, oil on canvas, 1807

Negative capability has become one of several staple characteristics of Romanticism, for the sentiment that informs negative capability nourishes reflection on human existence on many levels. We encounter this same sentiment in the thought of many existentialists. For instance, Gabriel Marcel, the French Catholic existentialist invokes concern for negative capability by contending that problem and mystery are different realms of human existence. Marcel understood that science merely deals with objects and physical processes. In other words, science concerns itself with technical problems. Scientific problems lack an existential dimension, for they remain external to man’s inner life. Marcel contends that persons experience life as a vital, ontological mystery.

Keats used Negative capability to reject the idea that man’s knowledge can become exhausted. Instead, negative capability does not startle the soul with too much knowledge or “amaze it with itself.” Keats adds in his letter:

Several things dovetailed in my mind, and at once it struck me, what quality went to form a man of achievement especially in literature and which Shakespeare possessed so enormously – I mean Negative Capability, that is when man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.¹

Part of Keats’ brilliance as a poet is his embrace of metaphysical postulates, the essence of which all forms of positivism aim to vanish from human life. Keats’ metaphysics is constructive, unlike positivist epistemology, which fuels the many-headed hydra of scientism that asphyxiates post-modern life. However, Keats’ rebuke of positivism is only one component of his romanticism. Negative capability also engenders a form of courage and heroism that comes about from letting life take its course – letting life be. This is comparable to Quijotismo in Cervantes’ Don Quijote.

For romantic poets and intellectually honest thinkers, human existence is rooted in mystery, though, not shrouded in it. Mystery itself is one of the truths of the human condition. Keats is not interested in erecting self-conscious epistemological fortresses. This is one reason why negative capability is vehemently opposed to all forms of positivism.

Martin Heidegger

Yet negative capability does not suggest that man turn away from science, for science is a natural response of human reasoning to questions that demand reflection. Science is only one of several tools that man utilizes to make sense of human reality.

The romantic poet is cognizant that the scientific method cannot solve the ontological mystery. One example of this is the question of why there is something rather than nothing, which existential thinkers like Heidegger and romantic poets like Blake embrace. Negative capability is an existential mood that enables man to be awed by the sublime. Given man’s inner dimension, we must ask ourselves what is the function, if not the purpose of existential interiority? By transcending the domain of the senses man learns to amplify the scope of reason.

For Keats, poetic sentiment enables man to remain open to Socratic irony. The realization that the more I know – the more I realize that I do not know it all – keeps man humble. Of course, the latter presupposes intellectual honesty.

The vast majority of people throughout history have lived by the rhythm of sunrise and sunset, and the seasons. It was not until the age of electricity that man’s scientific narcissism attempted to create a science of everything. What horrors does the latter entail?

Keats reacts to scientism and technology not because the findings of the scientific method are wrong, but because they are incomplete. Not permitting his worldview to become conditioned by the passing fashions of material existence, Keats’ thought suggests that an existentially vacuous existence bodes dangerous for man, for existential self-reflection conveys understanding – the form of reflection that leads to self-knowledge. Keats makes this clear in another letter to George and Georgiana Keats on April 21, 1819, where he writes;

There may be intelligences as sparks of the divinity

in millions – but they are not Souls till they acquire

identities, till each one is personally itself.²

Prof. Pedro Blas González

— Pedro Blas González is Professor of Philosophy at Barry University, Miami Shores, Florida. He earned his doctoral degree in Philosophy at DePaul University in 1995. Dr. González has published extensively on leading Spanish philosophers, such as Ortega y Gasset and Unamuno. His books have included Unamuno: A Lyrical Essay (Floricanto Press, 2007), Ortega’s ‘Revolt of the Masses’ and the Triumph of the New Man (Algora Publishing, 2007), Fragments: Essays in Subjectivity, Individuality and Autonomy (Algora Press, 2005) and Human Existence as Radical Reality: Ortega’s Philosophy of Subjectivity (Paragon House). He also published a translation and introduction of José Ortega y Gasset’s last work to appear in English, “Medio siglo de Filosofia” (1951) in Philosophy Today Vol. 42 Issue 2 (Summer 1998).

Endnotes:

- David Perkins (ed.), English Romantic Writers (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1967) p. 1209.

- Stanley Kunitz (ed.), Poems of John Keats (Thomas Y. Crowell, 1964) p. 125.

Leave a comment