Is Practicality Practical?

Is practicality practical? The answer is, probably not, or at least that it is hard to tell, and that practicality, in any field, might only be practical – or for that matter, recognizable – in the long term; and yet also that, in achieving its zenith of practicality, an innovation might only remain in that state for a limited vital period, after which its practicality would swiftly diminish, as though in accord with an inner law. Another probability is that anything eventually proving itself practical (a term that requires definition) likely originates in an idea that, in its moment, critics and naysayers, who look always for an opportunity to wag their tongues, roundly derided as impractical or fantastic, and which might indeed have been so in the context of its origination.

I

The Aerial Steam Carriage

From 1945 until about 1980 global air travel was an achieved, even a perfected, practicality. It qualified as practical in a number of ways. Technically speaking, the aeronautics industry, based on experience in building short-range passenger aircraft in the 1930s and long-range strategic bombers in the period 1935 – 1945, could now design and manufacture safe, reliable four-engine machines capable of crossing the Atlantic or the North American continent with forty or fifty passengers at about two hundred and fifty miles per hour. The Pacific airline routes were logistically more complicated than those others, but the new machines, mostly flying boats, did much to streamline passenger schedules by reducing the need for refueling stops. Previously, only the Zeppelin airships offered an alternative to sea-travel between Europe and the Americas, but their shortcomings told against them. A trans-Atlantic crossing on the Graf Zeppelin or the Hindenburg took four days, in the course of which passengers endured the restrictions of their small cabins and limited hygienic facilities. Hydrogen-filled airships also entailed an existential risk, as the fiery demise of the Hindenburg on attempting to tie up at Lakehurst, New Jersey, on 6 May 1937, demonstrated. The Hindenburg’s was not the only passenger-carrying airship disaster. The British airship R-101, in its time the largest and most technically advanced airship ever built, crashed in France on 4 October 1930 during a thunder-storm on a journey that would have taken her from Cardington to her final destination in Karachi. Enter the airliner, which would take up where the airship left off.

William Samuel Henson

In the immediate postwar decade, the American Douglas Type 4, Type 6, and Type 7, and the Lockheed Constellation embodied the paradigm of the successful continent- or ocean-crossing commercial airliner in the propeller age. Joining them somewhat later, the Vickers Viscount, employing turboprops, pioneered what the mid-range routes. Britain’s De Havilland Comet was the first jet-powered airliner, entering commercial service in 1952, followed by America’s Boeing 707 and Douglas DC 8, both of which entered service in 1958. Today’s air-travelers would be surprised – and no doubt pleased – by the passenger experience of that halcyon era. For one thing, the “jet way” had not yet been invented. Ticket-holders, formally dressed even when vacationing en famille, left the lounge, walked the tarmac to a portable stairway, and boarded the airliner from the ground en plein air. There was as yet no police-style herding and funneling of passengers in airports. Before the invention of the so-called hub-system in the 1980s, moreover, direct coast-to-coast and city-to-city flights were the norm for North-American air-travel; the airlines did not force travelers to fly, as they often do nowadays, hundreds of miles out of their way, delaying them so as to transfer from one aircraft to another, in sprawling hub-airports, in order to arrive by annoying detours at their final destinations. Advertisements from the slick magazines of the 1950s and 60s extol the ease and glamour of passenger air travel, emphasizing that such travel had adjusted itself to the needs of those who purchased the service.

The Islamic terrorist attack on the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center hammered the final nail into the coffin-lid of passenger air-travel’s clientele-friendly era. To the degree that the practicality of the institution corresponded to its convenience as considered from its clientele’s perspective, the current regime of airport-airline collaboration can no longer justify itself as practical, but merely as profitable. At best air travel is an unavoidable necessity for many people, especially businessmen, entailing gross inconvenience, ritual humiliation, and increasing uncertainty, given the laziness and cynicism of the providers, whether the flight will leave on time or arrive at the inevitable hub with sufficient promptitude for the traveler to connect with his continuation-flight, over which the same dire uncertainties hover. The patron-customer might well be refused the privilege of boarding in the first place even though he holds a valid ticket because of the dishonest scheme of overbooking flights. A modern airport resembles a Moloch-machine for treating men, women, and their children as though they were cargo or ballast – or sacrificial victims. It is nowadays a common calculation whether the distance required by an itinerary justifies submitting to the system or whether, under a certain number of miles, the personal automobile offers a better, a saner choice. The horizon of air-travel-avoidance expands regularly. This existing state of affairs roundly betrays the conceptual origin of continental and global air travel, which in its moment foresaw something like the genteel arrangements of the propeller and early jet ages. That moment of conception occurred, curiously enough, not in the 1920s or 30s, when commercial aviation was in its experimental and organizational stages, but much earlier, in the mid-Nineteenth Century.

John Stringfellow

William Samuel Henson (1812 – 1888) and John Stringfellow (1799 – 1883), patent-holders of the design for the Aerial Steam Carriage (Specification No. 9478 – issued in 1842) and incorporators with Frederick Marriott and D. E. Columbine of the Aerial Transit Company (1843) were born in the Romantic era. While it is true biographically that both men seem exemplarily Victorian something essentially Romantic adheres to their project. The same might be said of their better-known contemporary Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806 – 1859), who built the steamship Great Western and attempted boldly but unsuccessfully to drive a tunnel underneath the Thames. Flying machines, in the perfection of which Henson and Stringfellow cooperated, appear already in the poetry of Erasmus Darwin, William Blake, and Percy Shelley, just before and just after the turn of the century. Darwin’s Economy of Vegetation (1791), as unlikely a title as one might invoke, imagines in its first Canto “the flying-chariot,” powered by “unconquered steam,” winging its way “through the fields of air.” Writes Darwin: “Fair crews triumphant, leaning from above, / Shall wave their fluttering kerchiefs as they move.” Blake, in the visionary introduction to his epic poem Milton (1810), invokes the famous “chariot of fire.” Shelley, in his Witch of Atlas (1820), endows his titular sorceress with a flying “pinnace” or “boat,” in whose winged hull she flits among the clouds and “outspeeds the antelopes which speediest are.” Whereas Shelley’s aerial vessel, propelled by the witch’s fancy to flit where she will, belongs in the realm of myth and magic, Darwin’s belongs in the realm of boilers and machinery. Between them they nevertheless define the character of Henson and Stringfellow’s project: To realize a commercially applicable machine that, mastering long-range air-routes, would outcompete in swiftness any ocean-passage and, in effect, shrink the world time-wise.

That both Henson and Stringfellow saw the prospect of aerial passenger conveyance not in some meanly profit-grubbing, but, on the contrary, in a visionary way, their descriptions of the Aerial Steam Carriage and of the Aerial Transit Company abundantly indicate. M. J. B. Davy’s invaluable monograph (1931) on Henson and Stringfellow, Their Work in Aeronautics (The History of a Stage in the Development of Mechanical Flight, 1846 – 1868) quotes both men at length and supplies in its appendices both the full Patent Specification of 1842 and the incorporation agreement of 1843. The idea of the Aerial Transit Company caught the public imagination of the day and supplied journalism with a provocative gist for speculation. Henson and Stringfellow foresaw in their Aerial Steam Carriage a large machine of 150 feet in wingspan (the DC 4’s span was only 117 feet) and with a wing of thirty feet in chord or cross-section; a triangular tail serving as an elevator extended to the rear of the wing-structure, which in turn supported a gondola for the accommodation the power plant and presumably the crew and passengers or cargo. The two men estimated that the steam engine would weigh some six hundred pounds, delivering thirty horsepower-units to two large pusher-propellers mounted in the trailing edges of the wings. Henson and Stringfellow had put forth a design for the largest airplane yet envisioned by aeronautical engineers and the scale of their enterprise impresses. Davy affirms that “the monoplane structure of Henson’s project was founded on thoroughly sound engineering principles” with “the car, or body, of his aeroplane… designed with a view to the reduction of wasteful drag to a minimum”.1 Davy adds that “the features of the design… were to be found incorporated, in one way or another, in the majority of aircraft during the earliest years of successful flight – i.e. from the year 1903 onwards”.2

Frederick Marriott

for the Aerial Transit Company, Columbine wrote up a prospectus in a bid to raise funds, which Davy quotes. Columbine describes the flying machine and the transit scheme together as a “Great Project” whose “utility is undoubted, as it would be a necessary possession of every empire, and it were hardly too much to say of every individual of competent means in the civilized world”.3 Columbine remarks that: “This work […] presents a wonderful instance of the adaptation of laws long since proved to the scientific world combined with established principles so judiciously and carefully arranged, as to produce a discovery perfect in all its parts and alike in harmony with the laws of Nature and of science”.4 Contemporary illustrations archly romanticize the Aerial Steam Carriage. One such shows the machine in flight over an industrial park in London, with the factories at work, their chimneys issuing in smoke and steam, with the Thames in view, and with the dome of St. Paul’s distantly visible; the Carriage itself trails smoke and steam, while the two propellers spin in rotary blurs and pennants fly from the bracing-struts.5 Another lithograph shows a speculative way-station somewhere in the Indian subcontinent. The picture represents one Carriage taking flight by descending at forty-five degrees of angle along a ramp. A second machine in flight is either just arriving or has just launched itself into the air on the next leg of its journey. Quaint Mogul-style architecture looms in the foreground while a providential elephant carries riders in native dress, who observe the arrivals and departures in wonderment.6 Yet another lithograph gives a satiric speech to a proponent of the scheme: “This is no humbug to raise the wind, or treasures from sunken ships, but a genuine English speculation to go to the Valley of Diamonds for jewels or to China for the [illegible], and get back in four days. This is the sort of thing to put a girdle round about the Earth in 40 minutes to pull it out of the way of the comet”.7

Henson and Stringfellow never raised sufficient funds to build their full-sized Aerial Steam Carriage, but they eventually managed to scrape together enough money to construct a scaled-down version, which they tested albeit unsuccessfully a number of times in the period 1844 – 47. Subsequently, working alone but benefitting from his collaboration with Henson, Stringfellow produced a new model of the same scale and retaining the overall planform of projected large machine, but with internal structural alterations and a better engine. Not only Davy, but also more recently Maurice Kelly in Steam in the Air8 and Harald Penrose in An Ancient Air9 both affirm that Stringfellow’s model achieved sustained powered flight before reliable witnesses in 1848 and on more than one occasion. On 22 August 1848, for example, the model flew over a course in the Cremorne Gardens, London, for 120 feet before the engine exhausted its water supply and stopped generating steam. The famous “first” flight by the Wright Brothers, using an internal combustion engine, reached only to 120 feet – more than half a century later. Davy writes: “Stringfellow’s achievement in model flight was not, in all probability, greatly surpassed until Professor Samuel Pierpont Langley accomplished very prolonged flights in the air during 1896 and 1897 with a machine incorporating a much higher degree of automatic stability; though, in the interim, other successful experiments had been made, notably by Alphonse Pénaud and Lawrence Hargrave”.10

Isambard Kingdom Brunel

The efforts of Henson and Stringfellow qualify as practical in the sense that they were hands-on and technical, producing actual machines, one of which, a model, eventually flew; those same efforts qualify as impractical in that subscribers remained too few to finance the large proof-of-concept machine; and the machine, given the materials available, and the low power-to-weight ratio of the compact steam engines, probably lay beyond realization. Nevertheless, had the large machine appeared, and had it seen manufacture in numbers, organizing air-routes, if only at short range – between, say, London and Manchester, or across the Channel – would have been no more difficult than organizing railroad rights-of-way or oceanic navigation routes. It might indeed have been less complicated. Although little-remembered today, the reputations of Henson, Stringfellow, and other aeronautical pioneers endured into the early decades of Twentieth Century flight and probably influenced the practical arrangements of the first passenger airline services. The ambiance of the Aerial Steam Carriage and the Aerial Transit Company might also have insinuated itself into the contemporary “Steam Punk” aesthetic, which specializes in genre-fiction and cinema wherein visionary schemes such as Henson and Stringfellow’s counterfactually proved themselves in their time, leading to the early appearance of technologies that chronologically became practical only much later. A machine resembling the Aerial Steam Carriage appears in Czech filmmaker Karel Zeman’s film The Fabulous World of Jules Verne (1962).11 Director Stephen Norrington taps the same source of inspiration in his film The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003),12 where steam drives everything. Such nostalgia for what picturesquely might have been, but sadly was not, is, all by itself, culturally significant.

II

The Antikythera Mechanism

Modernity defines the practical first as what is materially and logistically possible and second as what is productively or logistically efficient: Praxis, for modernity, means doing things with the minimum of energy at the front-end (although that minimal quantity of energy might be quite large) so as to insure the maximum of physical results at the back-end. Any human concern is external. When modernity apprehends such non-physical notions as spiritual efficacy, cultural significance, and cosmic attunement, however, it knows not what to make of them; it would instinctively never assign them within the circle of practicality, but would laugh them out of court. Even a cell phone, which seems inert, moves people around by supplying them with cues and motives where to go (“let’s flash-mob the shopping-mall!”) thereby reducing them to so many logistical units. A mechanism, no matter how subtly wrought, that did nothing in the world of matter but let us say claimed only to generate metaphysical significance would likely strike a Twentieth-Century mentality as a gimmick, like a magic eight ball, but it could never truly understand it. A telling test-case of this assertion exists in an item discovered by Greek sponge-divers in 1898 in the submerged wreckage of a First Century BC Roman merchantman that foundered in a storm off the island of Antikythera and spilled its lavish contents across the ocean floor. In that extravagant debris were bronze statues in the Hellenistic manner, fine glassware, and hundreds of amphorae, the large elongated ceramic containers used for the shipping and storage of wine, grain, oil, cured olives, and pickled fish. All of that, for which Rome offered an eager market, is perfectly understandable in a modern-practical way, but one bit of salvage constituted an anomaly. A mass of corroded bronze encrusted with limestone revealed itself on close examination to be a tantalizing but not immediately decipherable mess of compact gears and rods – in other words, a mechanism.

Antikythera Mechanism

Hence the “Antikythera Mechanism.” The object – whatever it was – went with the rest of the loot to the National Museum in Athens, where it soon began to attract attention. For one thing, the consensus of scholarship assumed Antiquity never to have developed geared mechanisms, or at any rate to have produced only crude devices with two or three large wooden gears meant for banal applications, as in stevedoring. The puzzling brassy lump, as opaque as it was due to the dissolution of the metal and the infiltration of its structure by self-hardening sediments, nevertheless revealed even to superficial examination hints of a clockwork-like complexity hitherto thought to have come into being only in Western Europe in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries. Jo Marchant, in Decoding the Heavens: A 2,000-Year-Old Computer – and the Century-Long Search to Discover its Secrets,13 writes how early examiners took the Antikythera Mechanism for an astrolabe and sought to displace it to a later century by assuming, quite fancifully, another shipwreck on exactly the same site. The fact that one decipherable feature of the Mechanism appeared to be a moirognomonion or graduated scale reinforced the assumption. As Marchant writes, “The essence of an astrolabe, however, was something that […] new technologies could never replace.”14 Why would anyone substitute for the astrolabe’s elegant simplicity a complicated device with dozens or scores of close-fitting, geared parts? Yet John Svoronos and Pericles Rediadis, the earliest investigators of the Mechanism, could imagine for it no other function. Svoronos deliberately ignored the archaeological context of the find so as assign it a date in the Third Century AD. By the mid-1930s, research had stalled. World War Two would intervene before interest revived.

The resumption of research after the war swiftly saw two stubborn prejudices, which stood in the way of understanding the object, put to rest. Thanks to the intervention of none other than Jacques Cousteau, whose team swam down to the wreck and collected new data, the Late Hellenistic origin of the Mechanism affirmed itself in such a way as to become incontestable; and the idea of the Mechanism as a navigational instrument became unsupportable. As Marchant narrates, the picture gradually resolved itself of a cargo-ship being commandeered by a Roman general, probably Sulla (138 – 78 BC), on campaign in Ionia in order to transport back to Rome the tribute and booty accruing from his marches and sieges. The ship, whose class can be identified, indeed seems to have been seriously overburdened in its hold and thus vulnerable to the rough waters that it must have encountered. Even the point of departure and one of the ports-of-call could be plausibly inferred: The ship likely set out from the harbor at Pergamum and it likely stopped, possibly to load additional cargo, at Rhodes. The Rhodian connection is important. The island’s rulers could fairly claim to sponsor the most advanced scientific activity of the day, particularly in astronomy and mechanics, its research institutions having surpassed in their achievements those of Egyptian Alexandria. Some of the Rhodian scientists, moreover, worked in a tradition of mathematics and mechanics going back to Archimedes (287 – 212 BC), who is rumored to have experimented with gears and to have built working devices, some of which had a military application.

Jo Marchant

That the Antikythera Mechanism resembled either a planetarium or a zodiacal calendar, the work of two Englishmen, Derek de Solla Price and Michael Wright, and an Australian, Allan Bromley – all of whom in a twenty-year period from the 1980s to the early 2000s built conjectural reconstructions of the Mechanism based on x-ray examinations of its interior – had made clear. Scattered in Hellenistic Greek and in early-Imperial Latin literatures were descriptions, usually quite vague, of mechanical “spheres” whose automated movements could mimic those of the heavens. These descriptions bolstered the plausibility of those conjectural reproductions. The Mechanism itself, furthermore, boasted many Greek-language inscriptions hinting at a celestial orientation. The key to understanding the Mechanism therefore appeared to be the lore of Late Hellenistic astronomy. As does Marchant in her book, Alexander Jones in his Portable Cosmos15 singles out the Rhodian polymath Hipparchus (190 – 120 BC) as having a connection, at least indirectly, to the Mechanism. Marchant writes: “The astronomy embodied in the Antikythera Mechanism was state-of-the-art, and would presumably have needed the input of a major astronomer”.16 Hipparchus studied the precise mathematical calendars of the Babylonians. As Marchant relates, he then “used the Babylonian [numerical] data to derive numbers for the [existing cosmological] models and in doing so transformed Greek astronomy from a largely theoretical science into a practical, productive one”.17 According to Jones, Hipparchus was “the earliest known astronomer [to have] studied the Moon’s motions in relation to epicycles and eccenters”.18 Jones sees Hipparchus’ discovery of precession, for example, as “one of his most important accomplishments […] because it was a remarkable instance of scientific analysis […] at the threshold of what could be detected from the observational record available in his time”.19

As better knowledge of the Antikythera Mechanism emerged, and as the model-builders incorporated the newest discoveries, it began to dawn on interested parties that the Mechanism’s gearing encoded a sophisticated mathematics of the celestial motions. One would need to spring forward to Charles Babbage’s early-Nineteenth Century calculating engines to find an equivalent. What then was the Mechanism? And perhaps more importantly what was its function? In Marchant’s summation: Through graphic representations front and back, “the Mechanism displayed the state of the skies at any chosen moment in time”.20 Marchant speculates that “one possible purpose is to cast horoscope”.21 The First-Century BC date corresponds to the rising popularity of astrology in the Hellenistic world, Marchant remarks. Referring to the vague descriptions of orreries mentioned above, Marchant writes how “modeling the heavens with geared devices ran alongside a parallel philosophical tradition of modeling living creatures [such as] people, animals and birds”.22 Marchant cites the steam-powered figures of Bacchus and his cohorts attributed to another Hellenistic engineer, Hero of Alexandria. For Marchant then the most likely function of the Mechanism, which would originally have been the private property of a wealthy commissioner, was to cast horoscopes and to predict, by precise mathematics, the most propitious year, month, and day for various practical undertakings.

Derek de Solla Price

For Jones, as his title proclaims, the Mechanism was a portable cosmos, a mechanical representation of the universe, but not only of the physical universe. In its function as several types of calendars, it also related to the cultural, and particularly to the religious, universe. The front panel of the Mechanism framed a single large multi-purpose dial: One dial but with multiple pointers. The outermost ring of the dial represents the Egyptian solar twelve-month year; the next ring the zodiacal cycle. Within the zodiacal ring is the orrery, with the Earth at the center, surrounded in the familiar Aristotelian manner by the sun, moon, and planets. The designer has represented the moon by a ball whose rotation reveals the phases from new moon to full moon. The back panel boasts two dials, both using a single pointer that moves through a spiral pathway. The upper main dial encloses two smaller inset dials while the lower dial encloses one smaller inset dial. The upper dial represents the Metonic cycle, after Meton, a Fifth-Century BC Athenian astronomer. The Metonic cycle, a nineteen-year period, reconciles the lunar with the solar year. The right-hand inset dial concerns the alternating sequence of the four sacred athletic competitions. The left-hand inset dial concerns the Callippic cycle, another long-range celestial calendar for reconciling solar and lunar movements. The lower main dial concerns the Saros cycle, which predicts solar and lunar eclipses. The single inset dial, based on the Exeligmos cycle, compensates for a regular eight-year shortcoming in the Saros cycle. The explanations of these ancient calendars and of their inter-relations exceed the possibility of a capsule summary – especially one written by a mathematical ignoramus.23

In his Afterword on “The Meaning of the Mechanism,” Jones offers a thesis, how “each one of the Mechanism’s astronomical and chronological functions had a rich context in ancient Greek life and thought”.24 Jones treats with harsh skepticism attempts to explain the Mechanism by finding for it some quotidian application. In consequence of this attitude, Jones fits himself to probe somewhat more deeply than Marchant. “I do not believe,” he writes, “that [the Mechanism’s] purpose was to compute data or make predictions to be applied in some practical context.” To make as transparent as possible the miracle of the rare device, Jones puts two preliminary questions: “Who needed the full range of its displays?” and “what advantage did mechanization offer to outweigh cost?”25 After surveying a number of possibilities, Jones advances the conclusion that “what the Mechanism was really suited for is instruction – not so much the training of astronomers… but the diffusion of the basics of astronomy among students of philosophy and the educated elite”.26 No one should imagine a pedantic demonstration. As Jones writes, the Mechanism is “a moving image of the cosmos, [which] showed the coordination and counterpoint of celestial and mundane phenomena, all governed by the flow of time while obeying deep principles of regularity”.27 Jones’ term “image” is important. Greek would render it as idea, a word with a Platonic resonance. Jones’ phrase “deep principles of regularity” is likewise important, implying as it does that the cosmos is logical, in the sense of being articulate, and that phenomena therefore correspond to something like a grammar.

Michael Wright

That would be a divine grammar. For the Greeks and the Hellenistic peoples the planets appeared both as celestial objects and divinities. The Greek viewpoint imbued the whole celestial panorama with an aura of religious mystery. That the front dial of the Mechanism uses the Egyptian names for the months of the year links it as much to Neo-Platonism and syncretism as it does to the pure mathematics of Hipparchus and Geminus, which is foremost in Jones’ mind when he makes his characterization. The Hellenistic document known as The Divine Pymander of Hermes, for example, mixes religious mystery with astronomy and cosmology in a Neo-Platonic framework, in such a way that disentangling the strands defies any attempt in advance. When one thinks of the Antikythera Mechanism as Jones does, in the image of a portable cosmos, one should remain aware of the inextricable linkage of religion, science, and philosophy in the Hellenistic Era. Hermes, who figures in the Pymander under his Egyptian name Thoth, receives wisdom from Mind, the supreme principle of the universe. Mind says to Hermes: “For Generation and Time, in Heaven and in Earth, are of a double Nature; in Heaven they are unchangeable and incorruptible; but on Earth they are changeable and corruptible”.28 Again: “See also the Seven Worlds set over us, adorned with an everlasting order, and filling Eternity with a different course”.29 And again: “Behold the Earth in the middle of the Whole, the firm and stable Foundation of the Fair world, the Feeder and Nurse of Earthly things”.30

Marchant’s intuition that the Antikythera Mechanism belongs with the class of “engines” ascribed to Hero of Alexandria converges nicely with the theurgic context for the device just now proposed. Theurgy refers not only to the practice of rituals and formulas to make the gods appear but also to the theatrical preparations that ensure, at the end of the ritual or in response to the formula, that an appearance of such an appearance will occur. Thus to Hero commentary attributes, for example, mechanisms to make temple doors seemingly open themselves and images of the gods come startlingly to life. In the view of the modern mentality, theurgy belongs to the realm of hoaxes and frauds, but the modern mentality fails to understand the ancient practice. In the Platonic view, everything in this world is an image of an eternal model. At issue is the degree to which a thing, natural or artificial, adequately represents its eternal model. The more that artfulness can make the artificial representation resemble what intelligence strains to imagine that the model might be, the truer, the more admirable, the representation becomes, and the more likely it is to make a true impression on the one to whom its similitude to the eternal model is demonstrated. The maker of the Antikythera Mechanism strove through his complexity of gears and dials to represent a sublime truth, as much religious as scientific, as near to perfectly as he could. The Mechanism would have had as its “practical purpose” to effect an intellectual alteration in the witnesses of its operation such that each witness might come closer to the recognition of that truth, the axiomatic character of which meant that it could never be proven by a syllogism, but could only be revealed in its fullness.

III

Is there a Lesson for Conservatism?

Alexander Jones

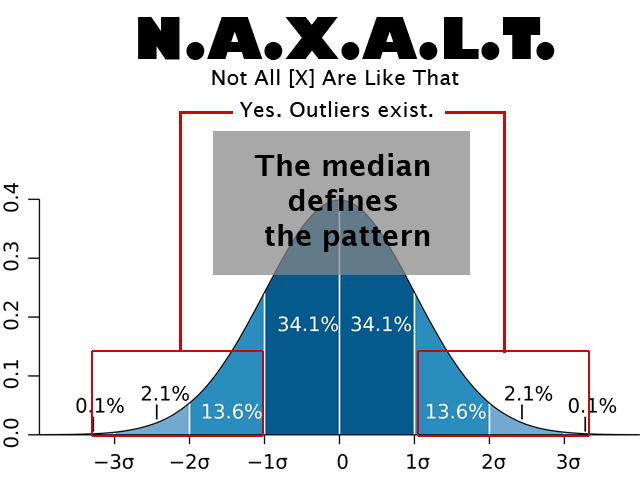

Insofar as the endeavors of a traditionalist type of conservatism are grounded, as the Antikythera Mechanism is, in the Logos or divine grammar of the cosmos, including the human part of the cosmos; and insofar as those endeavors subordinate the merely technical and the merely logistical to the fully human, as the plan of the Aerial Transit Company did, they will fall under the rubric of practical. Under its definition of practicality, of course, the liberal-modern order will declare any and every traditional or conservative enterprise, whether in politics or in the market, to be impractical. It will be useful in this regard to review what the liberal-modern order considers, not indeed as practical, but as impractical. The liberal-modern order considers the policing of borders as impractical and, on that argument, disdains to police borders. The proof that policing borders is practical is that it has been undertaken, successfully, many times in the past, and is still undertaken today, successfully, by many nations. The liberal-modern order considers discipline in the schools as impractical and, on that argument, disdains to implement discipline in the schools. The result is a public education system that has for decades produced an uneducated public conveniently amenable, from the viewpoint of social engineering, to having its marionette-strings pulled by hysterical propaganda campaigns. The liberal-modern order regards all prohibitions that originate in religion as impractical. This means, of course, that the liberal-modern order regards morality as impractical and, on that argument, disdains to heed it. Quite likely the liberal-modern order regards consciousness as impractical given that consciousness is partly moral conscience informed by religion.

Insofar as the thesis was true, it would follow that thinking was impractical – because a thing that does not exist can hardly exert practical influence in the material realm. The liberal-modern order indeed actively discourages thinking, as in its abysmal schools and universities, replacing actual thought with slogans and orders propagated through the ever-expanding, non-conscious “social-media” networks. The purpose of a cell phone, as earlier suggested, is to move people around en masse around on cue.

Samuel Pierpont Langley

What the liberal-modern order regards as practical, on the other hand, is in fact suicidal. It lacks all wisdom. When liberals tell conservatives that their proposals are impractical, it certifies the exact opposite. “Impractical” is simply another word for something that liberals oppose. Often in the liberal-modern vocabulary the word impossible substitutes for impractical, designating again something that liberals oppose. British voters could not possibly certify the motion to leave the European Union. Donald Trump could not possibly be elected President of the United States. Events like these teach the lesson that liberalism has no idea what is practical or impractical, possible or impossible, but only knows what it opposes. The liberal-modern order in all its manifestations is an aggressive Know-Nothingism which having fixed itself in place by taking over the institutions resists anything and everything that dissents from its fossilized, slogan-based second reality. The liberal-modern order is good at petulantly pretending, but not at clearly cognizing. None of this, by the way, contradicts the claim made earlier that the liberal-modern order defines the practical first as what is materially and logistically possible and second as what is productively or logistically efficient. Whereas it is difficult to build a wall and then again to maintain it; it is comparatively easy to knock down a wall. If rubble was the goal – and rubble seems to be the main product of the liberal-modern reaction against civilized achievement – then on its easy success the liberal-modern order might boast, and so it does, about its logistical efficiency.

Lieutenant M J B Davy

A liberal-modern study of the Aerial Transit Company would no doubt consist solely in denouncing it for being an instance of colonialism and racism. A liberal-modern study of the Antikythera Mechanism would no doubt consist solely in the attempt to attribute the device to an ancient Nubian feminist. The broadside satire of the Aerial Steam Carriage reproduced in Davy’s study, although it concerns a technical enterprise, instantiates a characteristic of liberal-modern rhetoric in respect of traditionalist and conservative propositions: It swaps the actual idea or proposal for a ridiculous caricature and then beats the caricature to death on the basis of its impracticality or its impossibility. Mr. Columbine lists the Aerial Transit Company’s proven tenets and describes it plausibly his prospective as “in harmony with the laws of Nature and of science” whereupon the broadside satirist claims that it is a plan to engirdle the earth with a great sling so as to drag it from the path of a comet. More important than the question whether a thing is practical or impractical, possible or impossible, from a traditional-conservative perspective, is the other, perennial question whether it is good, beautiful, and true. Certainly there is a great deal of beauty in Henson and Stringfellow’s vision of the Aerial Steam Carriage and there is a treasure-trove of profound truths – many of them unsuspected by scholarly commentary – in the miraculous gear-work of the Antikythera Mechanism.

Prof. Thomas Bertonneau

— Prof. Thomas F. Bertonneau is an American intellectual and professor. He has taught at a variety of institutions, and has been a member of the English Faculty at State University of New York, Oswego, since 2001. His articles and essays have appeared in a diverse array of scholarly journals including William Carlos Williams Review, Wallace Stevens Journal, Studies in American Jewish Literature, North Dakota Quarterly, Michigan Academician, Paroles Gelées: UCLA French Studies, and Profils Americains. He was a major contributor to the English section of The Brussels Journal. More recently, his work has appeared in The University Bookman, the John William Pope Center for Higher Education Policy as well as the websites The People of Shambhala and The Orthosphere. Prof. Bertonneau’s last contribution to the Sydney Traditionalist Forum was to its First 2017 Symposium (“The Future of Western Identity: Problems and Possibilities, Obstacles and Opportunities”) titled “Identity: The Future of a Paradox.”

Endnotes:

- M. J. B. Davy, Henson and Stringfellow: Their Work in Aeronautics – The History of a Stage in the Development of Mechanical Flight, 1840-1868 (London: Published by His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1931) p 98.

- Ibid.

- Cited in M. J. B. Davy op. cit. at p. 39.

- Ibid.

- See M. J. B. Davy op. cit. at front piece.

- Ibid. at Plate VI.

- Ibid. at Plate IX.

- Maurice Kelly, Steam in the Air: The Application of Steam Power in Aviation During the 19th and 20th Centuries (Pen and Sword Books, Ltd., Barnsley, South Yorkshire, 2006).

- Harald Penrose, An Ancient Air: A Biography of John Stringfellow of Chard, the Victorian Aeronautical Pioneer (Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C., 1989).

- M. J. B. Davy op. cit. at p. 73.

- “The Fabulous World of Julius Verne” (Director: Karel Zeman; Writers: Karel Zeman, František Hrubín, Jiří Brdečka, Milan Vacha; Released: Ceskoslovensky Statni Film, 1958).

- “The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen” (Director: Stephen Norrington; Screenplay by: James Dale Robinson [Based on the work of Alan Moore]; Released: 20th Century Fox, 11 July 2003).

- Jo Marchant, Decoding the Heavens: A 2,000-Year-Old Computer – and the Century-Long Search to Discover its Secrets. (Da Capo Press, London, 2009).

- Ibid. p. 47.

- Alexander Jones, A Portable Cosmos: Revealing the Antikythera Mechanism, Scientific Wonder of the Ancient World (Oxford University Press (America), 2017).

- Jo Marchant, op. cit. p. 265.

- Ibid. p. 270.

- Alexander Jones, op. cit. p. 192.

- Ibid. p. 113

- Jo Marchant, op. cit. p. 271.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. p. 276.

- Those wishing to know the details in their magnificent breadth and depth should consult Jones, especially his Chapter 3, “Looking at the Mechanism.”

- Jo Marchant, op. cit. p. 233.

- Ibid. p. 235.

- Ibid. p. 236.

- Ibid. p. 238.

- Dr. Everard (pseudonym) (trans.), The Divine Pymander of Hermes Mercurius Trismegistus (Edition of Charles H. Seers, Argyle St, Bath, 1883; reprinted by Wizard’s Bookshelf, San Diego, California, 1994 [1650]) p. 62.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

Citation Style:

This article is to be cited according to the following convention:

Thomas F. Bertonneau, “Is Practicality Practical” SydneyTrads – Weblog of the Sydney Traditionalist Forum (24 December 2017) <sydneytrads.com/2017/12/24/symposium-ii-thomas-f-bertonneau> (accessed [date]).

Leave a comment