“I think that there are six canons of conservative thought –

“I think that there are six canons of conservative thought –

- Belief in a transcendent order, or body of natural law, which rules society as well as conscience. Political problems, at bottom, are religious and moral problems. A narrow rationality, what Coleridge called the Understanding, cannot of itself satisfy human needs. ‘every Tory is a realist,’ says Keith Feiling: ‘he knows that there are great forces in heaven and earth that man’s philosophy cannot plumb or fathom.’ True politics is the art of apprehending and applying the Justice which ought to prevail in a community of souls.

- Affection for the proliferating variety and mystery of human existence, as opposed to the narrowing uniformity, egalitarianism, and utilitarian aims or most radical system; conservatives resit what Robert Graves calls ‘Logicalism’ in society. This prejudice has been called ‘the conservatism of enjoyment’ – a sense that life is worth living, according to Walter Baghot ‘the proper source of an animated Conservatism’.

- Conviction that civilized society requires order and classes, as against the notion of a ‘classless society.’ With reason, conservatives have often been called ‘the party of order.’ If natural distinctions are effaced among men, oligarchs fill the vacuum. Ultimate equality in the judgment of God, and equality before courts of law, are recognized by conservatives; but equality of condition, they think, means equality in servitude and boredom.

- Persuasion that freedom and property are closely linked: separate property from private possession, and Leviathan becomes master of all. Economic leveling, they maintain, is not economic progress.

- Faith in prescription and distrust of ‘sophisters, calculators and economists’ who would reconstruct society upon abstract designs. Custom, convention, and old prescription are checks both upon man’s anarchic impulse and upon the innovator’s lust for power.

- Recognition that change may not be salutary reform: hasty innovation may be a devouring conflagration, rather than a torch of progress. Society must alter, for prudent change is the means for social preservation; but a statesman must take Providence into his calculations, and a statesman’s chief virtue, according to Plato and Burke, is prudence.

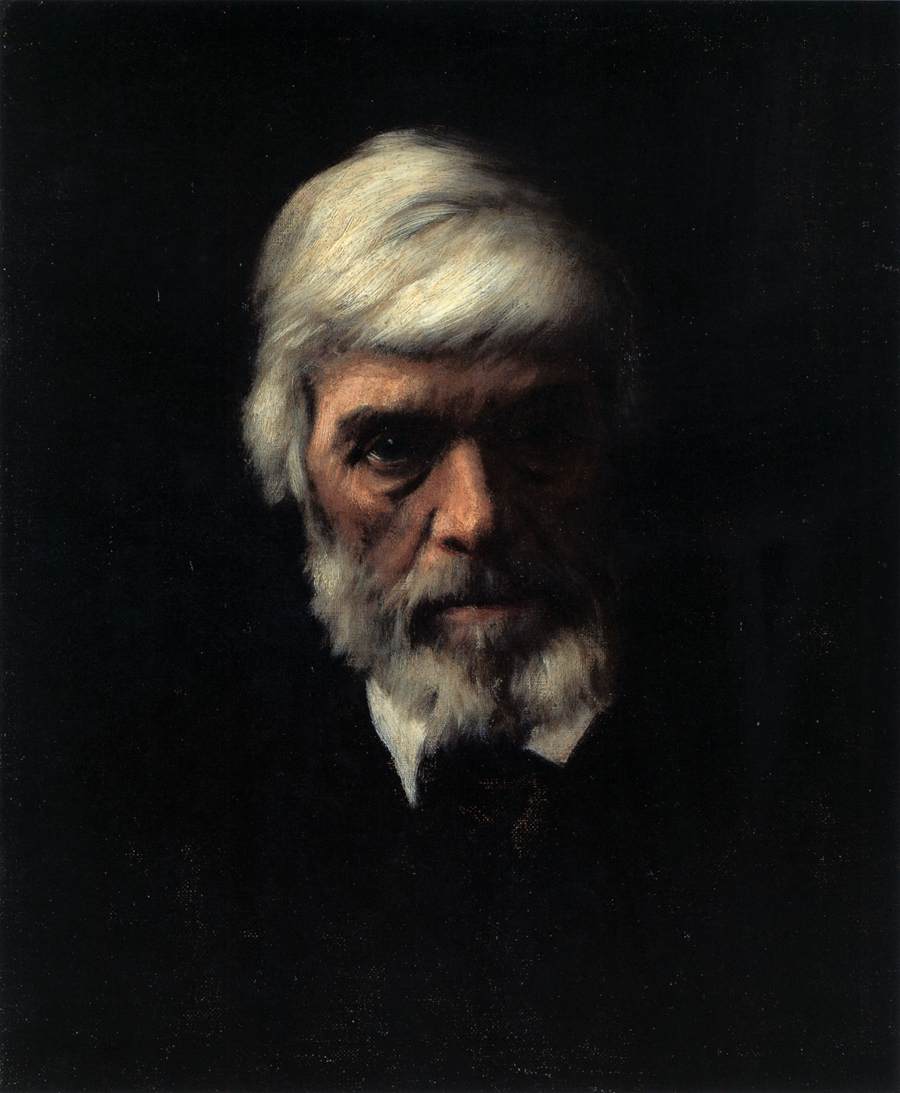

“Various deviations from this body of opinion have occurred, and there are numerous appendages to it; but in general conservatives have adhered to these convictions or sentiments with some consistency, for two centuries. To catalogue the principals of their opponents is more difficult. At least five major schools of radical thought have competed for public favor since Burke entered politics: the rationalism of the philosophes, the romantic emancipation of Rousseau and his allies, the utilitarianism of the Benthemites, the positivism of Comte’s school, and the collectivist materialism of Marx and other socialists. This list leaves out of account those scientific doctrines, Darwinism chief among them, which have done so much to undermine the first principles of a conservative order. To express these several radicalisms in terms of a common denominator probably is presumptuous, foreign to the philosophical tenets of conservatism. All the same, in a hastily generalizing fashion one may say that radicalism since 1790 has tended to attack the prescriptive arrangement of society on the following grounds –

- The perfectibility of man and the illimitable progress of society: meliorism. Radicals believe that education, positive legislation, and alteration of environment can produce men like gods; they deny that humanity has a natural proclivity towards violence and sin.

- Contempt for tradition. Reason, impulse, and materialistic determinism are severely preferred as guides o social welfare, trustier than the wisdom of our ancestors. Formal religion is rejected and various ideologies are presented as substitutes.

- Political leveling. Order and privilege are condemner; total democracy, as direct as practicable, is the professed radical ideal. Allied with this spirit, generally, is a dislike of old parliamentary arrangements and an eagerness ofr centralization and consolidation.

- Economic leveling. The ancient rights of property, especially property in land, are suspect to almost all radicals; and collectivistic reformers hack at the institution of private property root and branch.

“As a fifth point, one might try to define a common radical view of the state’s function; but here the chasm of opinion between the chief schools of innovation is too deep for any satisfactory generalization. One can only remark that radicals unite in detesting Burke’s description of the state as ordained by God, and his concept of society as joined in perpetuity by a moral bond among the dead, the living, and those yet to be born – the community of souls.”

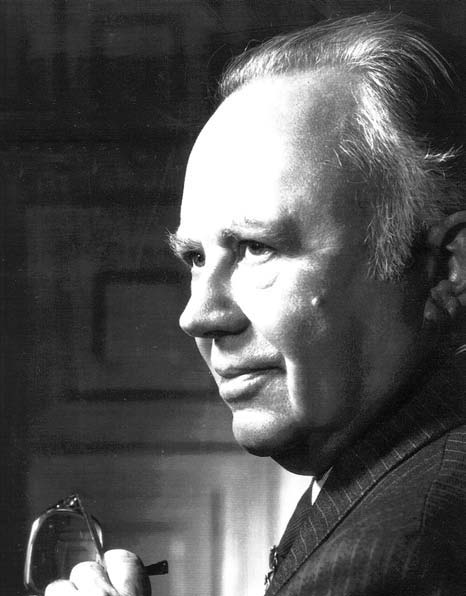

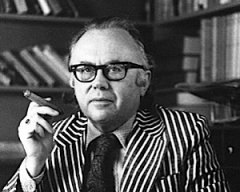

▪ Russell Kirk, The Conservative Mind – From Burke to Eliot (7th rev. ed., Regnery Publishing, 2001) pages 8 through to 10.

Leave a comment