“I hold it to be the inalienable right of anybody to go to hell in his own way.”

— Robert Frost

Robert Frost (1874-1963)

One of the most confusing developments of the late 20th/early 21st century is the sudden eruption of the cause of “natural rights” in the Left. Natural rights were, of course, the fundamental cause of the Classical Liberals. From there, the idea was ushered into Conservatism via the Fusionist process, and Conservatives who had no time for the idea were gradually phased out. The far-Left was originally content with agitating with workers’ rights only, but now they brandish the term far and wide, with all the finesse of a sans-culottes. It’s entirely part of our vernacular. Which, of course, doesn’t mean it’s at all a reasonable idea to begin with.

For better or worse, a post-Enlightenment society is entirely tethered to the idea of natural rights. We all believe we have them, we all define them differently, and we all demand that they be met. But the idea that we have rights at all is an anomaly. Put into historical context, the “rights of man” became such a bother in the mid- to late- 18th century because a group of thinkers—among them Locke and Rousseau, drawing from the earlier work of Hobbes—decided we were born in a state of lawlessness (often called barbarism) and give up our rights to live in a harmonious society.

From there, the whole twisted debate has proceeded. Men assert their right to philander. Women assert their right to vote. Same-sex couples assert their right to marry. Conservatives assert their right to bear arms. Liberals assert their right to take them away. It’s all rather nonsensical. There’s no scientific, rational, or religious grounding for the idea of “natural rights”.

Curiously, however, science, reason, and religion all speak of laws.

I. Law & Right

Patrick White (1912-1990)

In science, for example, we speak of the law of gravity. Gravitational forces pull objects toward the center of gravity. That center of gravity is different on the Earth than it is on the sun: if you somehow manage to throw a baseball from the surface of the sun, it won’t fly toward the Earth. And vice-versa. A baseball doesn’t have the “right” to fly at the sun, it has the obligation to. It’s entirely against its will. So, too, humans don’t have the “right” to obey or disobey gravity. There’s a wonderful line from Patrick White’s Ham Funeral—“Will said: a man only ‘as to bounce like a ball to know ‘ow much of ‘is will is free.”

In the West, with our abundant food and shelter, we pride ourselves on how “free” we are—we can put on a white shirt one morning, and a black shirt the next; we can read Dickens one day and Belloc the next; we can eat lamb one day and tofu the next. But if we were to find ourselves stranded in the middle of the Sahara, those freedoms would disappear. Our rights are so often contingent on our time and place. If we have no clothes, we can’t choose what we wear. If we haven’t any books we can’t choose what we read. If there’s no food available we’ll starve. Those are scientific laws, laws of nature and the physical realities we have no influence on.

Rationally, too, the idea that we are born with rights doesn’t quite pan out. You might say to me, “I think it’s perfectly reasonable that I have the right to smoke pot.” Where did you get that idea? Either from the idea of positive liberty, where the nature of the universe is such that you’re endowed from birth with the right to smoke pot at your pleasure, or from negative liberty, where no one is endowed with the right to stop you.

The argument from positive liberty is weak: if you have the right to smoke weed, I say I have the right to stop you. You want to smoke weed, I don’t want you to. Ultimately, we admit, it’s a matter of personal sovereignty—but what gives you so much autonomy over your body? Because you want it to be so. You feel your natural state is one where you can do whatever you want, usually with the condition of “so long as it harms no one.” Now who’s to decide if it does or doesn’t harm me? If I’m a raving moralist—absolutely distraught and plunged into profound suffering by the idea of anyone smoking weed—does your recreational pleasure come before my physical health? There are many such moralists; the Republican Party is full of them. Thousands of cranky old men and women’s mental health will suffer gravely at the expense of the pothead’s selfish desire. You tell them to get over it and stop cramping your style; they tell you to get over it and stop cramping theirs.

This is more or less the debate that rages over drug legalization, and the principle it’s grounded in is utterly convoluted. Wants and rights are usually equivocal. Of course there are folks who say, “I would never smoke pot myself, but I think others have the right to.” Yet you don’t hear people say, “I don’t want the right to smoke pot, but I think other people should have that right.” We believe in the rights that we want to exist.

This is more or less the debate that rages over drug legalization, and the principle it’s grounded in is utterly convoluted. Wants and rights are usually equivocal. Of course there are folks who say, “I would never smoke pot myself, but I think others have the right to.” Yet you don’t hear people say, “I don’t want the right to smoke pot, but I think other people should have that right.” We believe in the rights that we want to exist.

The negative liberty argument is already disproved: both come down to the question of, “If government exists to stop people from hurting each other, where can we logically draw the line?” The line always has been, and always will be, arbitrary. That a government should go about drawing arbitrary lines allotting freedom and regulation according to people’s conflicting desires and oftentimes improvable needs shouldn’t sit easily with anyone. One alternative is total anarchy, I suppose, but perhaps we should leave that issue for another time.

Another example is the gun rights debate. Seldom do people say, “I have the God-given right to bear arms… But I think banning them would do a world of good.” Our idea of rights is always in line with the rights we want to have, even if we don’t wish to exercise them.

Remarkably, the Christian and Jewish Bibles don’t say a word about rights as we understand them now. They speak of laws, duties, and justice. It is just to feed the poor. It is wrong to murder. It is just to clothe the naked. It is wrong to cheat on your spouse. We don’t have the right to not do those things, we only have the agency to do what is wrong. Nowhere in Western Civilization is it said, “You have the right to throw a brick through your neighbor’s house, but you’ll just go to jail.” Rights are not the same thing as agency. We have the physical capability to do certain things, and often we have the desire. But we don’t always have the right. So, too, we can’t say God gives us rights merely because He gives us agency. That we have the ability to do something doesn’t mean we have the right. So a question of “rights” can’t be settled by equating “rights” to “agency”.

If natural rights do, in fact, exist, we should at least be good enough to admit that we’re not going to figure out what they are. Anyway, if the last two hundred years are any indication, we’re not even close. But that’s not important. If we put our heads together we can work out a more sensible and tangible formulation of rights that doesn’t appeal to horrible abstractions.

II. The Social Contract

Edmund Burke (1792-1797)

The Social Contract theorists, diverse as they are, almost exclusively confess to the idea of Natural Rights. To them, we’re all born in an anarchistic state of unfettered rights, and by entering society (entirely against our will, nonetheless) we sacrifice certain freedoms to participate in that society. If we don’t agree to all the terms, oh well. If we don’t want to participate at all, too bad.

Edmund Burke alone among the Social Contract thinkers seems uncomfortable with this idea. He saw that barbarians, those stranded in the Sahara (literally or figuratively), weren’t very free at all. It would be bizarre to say that subjects of a theoretical tyranny in a country where food and shelter is abundant is more free than a man on a boat lost in the middle of the ocean without food or water. Rights, Burke claimed, are a product of, rather than a condition for, the social contract. We have rights because our forefathers killed other people’s forefathers to guarantee that we can actualize our agency. When Cambodians wanted to not suffer murder and enslavement, they overthrew Pol Pot. When Libyans got sick of Gaddafi stopping them from living prosperously and liberally, they took up arms and massacred him and his supporters. They didn’t have the luxury of toying with rational, philosophical arguments. They were brutally oppressed; they didn’t want to be anymore; they revolted.

If we were to extrapolate that sentiment with the example of Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge cadre with guns forced their will on the dissenting groups with guns. There was no arrangement between the two, so the Khmer Rouge had free reign over Cambodia. The balance of power shifted when the dissenters with guns became more numerous and/or well armed and/or more strategic than the Khmer Rouge. Both had a social arrangement: one was totalitarian and genocidal (strict terms, vicious enforcement), the dissenters’ new arrangement is more liberal (lenient terms, lenient enforcement).

This might sound like a “might makes right” sort of argument, but the reality is that Mother Nature or Aristotle or God isn’t going to physically stop anyone from taking away what you consider your “rights”. If someone tries, you have to stop him. Whatever the more profound philosophical implications are, that’s how the world works. All the universalist organizations such as the United Nations or the International Courts of Justice put together couldn’t change the fact that men can use violence to take what they want. As Burke said, “When bad men combine, the good must associate; else they will fall one by one, an unpitied sacrifice in a contemptible struggle.”

(Note also that none of this assumes that the absence of individual rights necessarily gives those “rights” to the government. If you don’t have the natural right to bear arms, that doesn’t imply that the government has the right to take your arms away, etc.)

If we can agree that a “right” is, (a) not natural, and (b) determined by the power of those who enforce its terms, the decisions we make in the future of government will be much less volatile and more conducive to the public wellbeing, as all political discourse is when the participants accept reality in place of unfounded abstractions.

III. Natural Law

The Conservative alone seems to understand this and grounds his thinking in natural laws rather than natural rights. Classical liberals fawn over the free market, yet you’ll never hear them say, “I think Marxism is better for humanity, but the market has its rights and must be obeyed.” They believe in the free market because they want it to be that way. Marxists, too, seldom say, “I think the free market would benefit mankind infinitely more than Socialism, but Communism is inevitable.” They believe in the rights of the capitalists and the workers, respectively, because they think they’re the best system we’ve got. Their belief in rights isn’t really rooted in reason or science—for science and reason are used to justify both Capitalism and Socialism—but because they want them to be right.

As Roger Scruton says,

Here, very briefly, is what serious intellectual conservatives believe: society is an association of individuals who are not free by nature but who may become free through their social relations. It is not a contract, because the majority of its members, being either dead or unborn, are not in a position to signify their assent to the arrangement, and because even the living members acquire the ability to contract only as a result of their social membership and not prior to it. Individuals have rights, but only because they also have duties and responsibilities, and none of these things are “natural”.

What we might say, as an aside, is that Burke’s and Scruton’s differences with the idea of a “social contract” is a question of semantics: both essentially say the same thing. Burke explains:

[The Social Contract] is a partnership in all science; a partnership in all art; a partnership in every virtue, and in all perfection. As the ends of such a partnership cannot be obtained in many generations, it becomes a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are to be born. Each contract of each particular state is but a clause in the great primaeval contract of eternal society, linking the lower with the higher natures, connecting the visible and the invisible world, according to a fixed compact sanctioned by the inviolable oath which holds all physical and all moral natures, each in their appointed place. This law is not subject to the will of those, who by an obligation above them, and infinitely superior, are bound to submit their will to that law.

Roger Scruton, British author and philosopher.

We needn’t take issue with whether or not we call the arrangement a Social Contract. Personally, I don’t see why we shouldn’t use the term and understand that it includes multiple generations’ negotiation and renegotiation of the terms of that contract.

Indeed, what Scruton takes issue with is the idea of a fixed contract, one where a violent revolution establishes some set-in-stone constitution that future generations must adhere to without question (the United States, France). Usually they claim that these terms are inviolable because they’re God-given or otherwise perfectly natural to human beings. So, then, how can we say governments can’t quarter troops in private homes during peacetime? Because it’s perfectly “natural”, as though it’s written in the trees, in the stones, in the babbling brooks. Property, too, can’t be a self-evident right, as though it were physically impossible for a thief to break into a house and steal a woman’s jewelry box. A thief can’t break into a house and steal the house—the law of gravity won’t allow that. But there’s no law of nature that will stop him from taking a few trinkets. No, these rights aren’t natural. They’re afforded in an agreement between people and maintained by force. That’s the reality.

This may sound like more of an argument for absolute democracy than conservatism, but democracy implies that a democratically run government (even if only literally a “government”—that which governs the conduct of certain people) has certain rights.

Rather, we have what Burke calls entailed inheritance: that the powers of the individual and the government are the product of our ancestors’ struggle to secure our ability to act on our agency—our true rights. If our rights are sacred, it is because our Forefathers shed their blood securing them for us. And, when the time comes, we will be called upon to shed our blood that those rights might be passed to our ancestors.

What naturally follows is the question, “To what extent can we claim these ‘rights’?” Liberal conservatives might freeze those rights here and now: free markets with a permissive society. Reactionary conservatives1 would see many of those rights repealed. Classical Liberals, socialists, progressives, and other left-wing thinkers (including our friends at the Frankfurt School) reject entailed inheritance altogether and embrace the idea of natural rights with great vigor; their illogic is lost to us.

The Traditionalist, otherwise known as the Classical or Burkean Conservative, approaches the matter of conserving and progressing rights more holistically, more scientifically. The difference between Classical, Liberal, and Reactionary conservatives is more one of framing than anything else. The Classical and Liberal Conservative are both comfortable with modernity—that is, they’re at ease with the fact that it is not the same day today that it was two hundred years ago on the same calendar date. We understand that time moves forward, yet we do not allow it to push us forward nor do we fight against its current. The Classical and Reactionary Conservative, on the other hand, are both uncomfortable with the modern world. The Liberal Conservative is overall comfortable with the modern state of affairs—such as multiculturalism, the welfare state, free market capitalism, and/or relaxed laws concerning victimless crimes. He places great value in personal freedom, and believes more freedom is almost always a good thing. The Reactionary Conservative fights the flow of time rather than the modern world. The Reactionary Conservative is often a Medievalist or a Victorianist or some other Era-ist, believing the course of history was positive until a certain point, and would turn back the clock to that exact period.

Henry George (1839-1897)

The Traditionalist is suspicious of absolute political values: neither freedom nor order, progress nor stagnancy, are always good in gigantic doses. Value judgments are made according to the wellbeing of society and the individuals that comprise that society. In economics, for example, the Traditionalist often has sympathies with Distributism: history has taught us that both private property and economic autonomy benefit society, though pure Capitalism and pure Communalism have proved ruinous. The social views of the Traditionalist are based in natural observations: man and woman create child; therefore, that essential unit is beneficial to society and should be given a place of special regard, guarded, and encouraged. Men are well served when they possess the right to bear arms, but private ownership of, say, a functioning tank would be a recipe for disaster. So gun rights must be permitted, but not unrestrictedly. None of these are natural rights; none of these are regarded as permanently fixed. They just happen to work, and have worked for a very, very long time.

The governing principle of these rights is, of course, justice: our agency must be limited by what is just and unjust. As Henry George phrased it (approximately), “That which is unjust can really profit no one, and that which is just can really harm no one.” We can’t authoritatively speak of right and wrong, but of just and unjust.

IV. The Foundations of Order

Why do we even desire freedom, anyway? On the one hand, we have the moral relativist or neutralist case: All or most of my actions do not have measurable moral significance. The assumption, then, is that governments should not restrict citizens based on a moral appraisal. The moral objectivist case is, instead: I don’t want to be subjected to the potentially immoral decisions of my government. This, I believe, is the original argument for increased liberties in Western society: rather than a rejection of public morality, it was more a rejection of what they perceived to be their government’s own poor standing in relation to the moral compass. I doubt anyone was thinking, “I have the right to bread,” so much as, “It’s wrong to deny me bread when you have more than enough.”

Whatever we think of the French Revolution (I try to think of it as little as possible), that common-men were deprived of possibly available necessities is indisputable. This inequality was upheld by a perceived Divine Right of Kings that extended to the aristocracy. So the French Revolution wasn’t a revolution of Those-Who-Believed-in-Rights against Those-Who-Didn’t. Most of the revolutionaries didn’t take up arms in pursuit of a philosophical idea, and there wouldn’t have been any Revolution at all if they were well fed. They fought from their empty stomachs, resentful of those who lived luxurious lifestyles while they went hungry.

Whatever we think of the French Revolution (I try to think of it as little as possible), that common-men were deprived of possibly available necessities is indisputable. This inequality was upheld by a perceived Divine Right of Kings that extended to the aristocracy. So the French Revolution wasn’t a revolution of Those-Who-Believed-in-Rights against Those-Who-Didn’t. Most of the revolutionaries didn’t take up arms in pursuit of a philosophical idea, and there wouldn’t have been any Revolution at all if they were well fed. They fought from their empty stomachs, resentful of those who lived luxurious lifestyles while they went hungry.

Even the Highest of High Tories, who detests everything remotely proletarian (even, if it’s possible, La Marseillaise, that undeniably beautiful anthem) wouldn’t say, “The aristocracy had the right to starve whom they wanted, and the French people should have understood their obligation to the upper classes.” Nonsense. That’s a very Libertarian argument, perhaps, but not a Conservative one. The Conservative is more conflicted. I think the internal dialogue would be, “Well, the aristocracy should have done its part to ensure the people were fed, but the French Revolution was inexcusable.” Edmund Burke was initially in favor of the Revolution’s aims, but when the cause of liberty was washed away by the murderous pursuit of an unintelligible populism, he became its greatest enemy in the British Isles. Burke’s was the last of those generations who never feared the cause of increased freedom could mean an ideological madness—an all-consuming, unnatural egalitarianism.

This is key to understanding the roots of Conservatism. As we established with Burke’s “entailed inheritance”, to increase liberty didn’t mean to intellectually realize a new right that one decided to give one’s self. To secure a “right” meant to declare one’s independence from a moral wrongdoing. It was to respond compulsively, like a falling baseball, to the Laws of God against the lesser dictums of men. As Edouard Recejac wrote, “It is one and the same to be ‘Holy’ and ‘free’, and the mystics are right when they say there is no other evil than sin, and sin is everything which entails a loss of Freedom.” The opposite of right isn’t tyranny. The opposite of right is wrong.

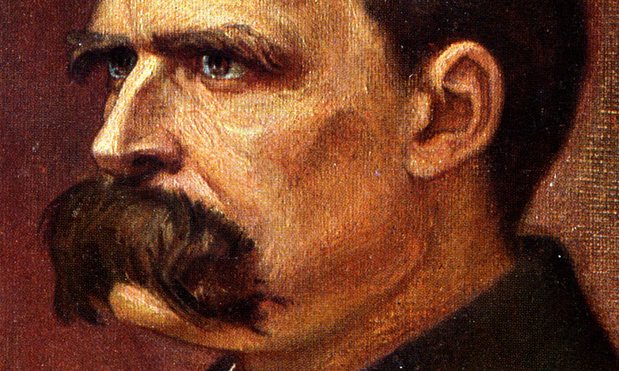

Joseph de Maistre (1753-1821)

This was the original criterion for rights. Men and women fought to free themselves from evil. Conservatives—like Burke, of course—understood this, and endorsed the cause of those who sought to right injustice. But when the idea of “natural rights” became increasingly abstract, Conservatives were at a loss to understand the cause, and could only see senseless violence.

Hundreds of years of inculcation by our post-Enlightenment education system has made us reflexively understand the French Revolution. We’re made to think like they do, and we can no longer place ourselves in the pre-Enlightenment mindset without great effort. Now, when we think rights, we understand “things people should be allowed to do regardless of what someone else’s moral or philosophical principles say.” We can see that this is almost the opposite of what our forebears understood.

As we’ve established, it would have been no help for the Duc d’Aumont to run to the gates as a mob of sans-culottes charged his estate shouting, “You can’t do this, I have the right do starve you if I want!” Whether anything of the sort actually happened, there’s no evidence that God opened up the sky and told the revolutionaries to go home. And when the Nazis occupied France, the right to Freedom of Religion was no use to those French Jews who were deported to concentration camps in the east. It has always been man’s obligation to arbitrate his own fate. We can fight for any right we want; we can have any right taken away. The question is how we establish what will give us “freedom from sin”, or, in lay terms, autonomy from another’s erroneous decisions.

Perhaps, dear reader, you’ve got a sense of what the best struggles for liberty have in common: a shared set of morals. And in the West, we cannot but understand that this moral sense is derived from Christianity. To be free was to be independent from evil and conform one’s agency to good. Burke understood that aristocrats possessed a sort of Divine Right to rule, but also understood that they’d failed to live up to the very fundamental Christian charge: “For I was an hungered, and ye gave me meat…” Burke applauded those Frenchmen who threw off the injustice of glutton, but recoiled at the injustice of egalitarianism. I believe he would strongly agree with C.S. Lewis’s formulation of democracy, which includes:

I believe that if we had not fallen […] patriarchal monarchy would be the sole lawful government. But since we have learned sin, we have found, as Lord Acton says, that ‘all power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.’ The only remedy has been to take away the powers and substitute a legal fiction of equality.

No doubt “equality” is the wrong word in this context, but the idea itself is solid. Burke was not a strict absolutist (which would have been unusual for an Englishman regardless) but rather a believer in just rule. There was no magic formula—“put it to a vote” or “as the King shall decree”—for good government. There was a sense of Right and Wrong, institutions set forward to preserve those Rights, and a constant struggle between masses of men to see that the Right triumphed over the Wrong.

C. S. Lewis (1898-1963)

But, like the Revolutionaries, our modern world has rejected an objective sense of morality, and with it a coherent system of rights. When we’ve decided that there is no objective idea of a moral “Right”, then “Right” must then become synonymous with “permission”. For example: We no longer believe in the goodness of marriage, so we’re forced to ask the government for permission to marry. No longer does the State participate in a civil (let alone religious) rite, but simply facilitate a formality that the individual participants may or may not give meaning to. Despite what Progressives claim, it has nothing to do with love or happiness. The government can’t legislate either of those things. They can only permit two people to marry, and perhaps those two people love each other. That’s no one’s call but the participants. But before ideology, before political science, there was right and wrong. Happiness and love were right; promiscuity was wrong. Marriage was an institution geared toward those and other accepted goods. Now it’s not geared toward anything.

That might be a bit sad, but sentimentality isn’t justification for any political measure. Rather, we should understand that, when we surrender the most basic reason for our rights, they’re indefensible. We can more or less agree on what our responsibilities as Christians are—what conduct is proper and what is improper—and so we can clearly identify what sort of decisions we oughtn’t be subjected to. When this first premise disappears, the debate to define the naturalness in natural rights is entirely one of individual preference. Should we choose to live without Christianity, our natural and common moral order, we must also be content to continue in our present state of unguaranteed and infrequent liberties, as well as our constant and bitter struggle against our neighbors for empty influence and domination.

The French Revolution: an assertion of right, as one elite replaces another.

The extreme libertarian answer is, of course, to make rights so profoundly broad that everyone is independent from any potential influence they find morally disagreeable. As the saying goes, “We don’t know if Libertarianism works or not because it’s never been tried.” That’s certainly true, but it hasn’t been tried because, beneath our “Enlightened” upbringing, we maintain a discomfort with amoral government. The common rebuttal is that, with a government so small, there’s nothing to guarantee another band of armed thugs won’t come along and depose the armed thugs we happen to pay our taxes to. This charge, made by non-Libertarians of both the right and the left, is a tacit acceptance of the original premise of this essay: there are no rights but those we secure on firm moral grounds. Or, in other words, we’re entirely unable to resign ourselves to what we consider immoral or amoral government. So we band together with those who share our moral standards and form factions, parties, armies… And we do war with those who disagree with our moral standards. (This is, of course, once we’ve passed beyond the most basic wars of resources.)

Since we’ve obliterated our common grounding in right and wrong, our task, then, is to resolve ourselves with a new moral standard, return to our traditional one (Christianity), or let injustice reign while we squabble. The Christian code of social and economic justice seems perfectly acceptable to me. All I can do is glance over our history books and see that no people informed by any other standard have enjoyed so many true rights and enjoyed such wide prosperity: not the pagans, not the Far East, not the Muslim world, not Africa, not the Fascists, and not the Communists. Christianity has been our greatest, truest success.

V. In closing

The Frankfurt School depends on us indulging them in idea of “natural rights”. It’s become the most wickedly defended myth in Western civilization. One may transgress religion, or monarchy, or patriotism, or family, or honor—but never Natural Rights. They’ve plucked workers’ rights exclusively from the vast illusory garden; widened their scope to such extremes as “gay rights”, “refugee rights” Etc.; and constructed a whole dogma to proclaim its coming in glory. And so they must. No reasonable person could any longer look back at the disasters of Communism and consider subjecting themselves to the same. The appeal of their rhetoric is ashen and dead, so they no longer try to convince us of the goodness of Communism (since we’ve thrown out such trifles altogether). Now they emphasize that Communism is inevitable, meaning that works rights are only natural. “Better to stand on the winning side of history,” the radical Leftist says, abhorrent as the outcome might be. Then again, if it is “natural”, who could we be to stand in the way of that tumultuous Progress anyway?

But wherever we may have benefited from the Age of Enlightenment, we must face the fact that we’ve only disoriented ourselves by abandoning the common principles that allowed us to see the world reasonably. We’re told to view our civilization like a horse race, to put our money on the jockey we predict will win out in the end. The safe bet, they say—the modest but assured return, the three-to-one—is Marxism. From what we know, it’s almost always brutal and lifeless and oppressive; its most idealistic incarnation has never been seen on this earth and is incomprehensible to us. Yet we ought to place our bets with the far-Left: after all, their victory is inevitable. They’re only fighting for natural rights.

But wherever we may have benefited from the Age of Enlightenment, we must face the fact that we’ve only disoriented ourselves by abandoning the common principles that allowed us to see the world reasonably. We’re told to view our civilization like a horse race, to put our money on the jockey we predict will win out in the end. The safe bet, they say—the modest but assured return, the three-to-one—is Marxism. From what we know, it’s almost always brutal and lifeless and oppressive; its most idealistic incarnation has never been seen on this earth and is incomprehensible to us. Yet we ought to place our bets with the far-Left: after all, their victory is inevitable. They’re only fighting for natural rights.

Our only hope, in the face of these tried-and-true distortions, is to bring ourselves back to the Traditional frame of mind. We mustn’t think “right and wrong” are separable from “right and tyranny”. What is right is always liberating, and what is wrong is always tyrannous. To secure our Rights—justice, virtue, and freedom—it’s up to us to plant our feet in the ground and claim them. The world, we know, won’t do us any favors. God seems inclined only to help those who help themselves. All we have is our conscience and the ability to speak to the most reasonable and humane parts of our fellow man. Our common sense and our ethical sense are both innate and never contradictory. So we must then proceed to speak diplomatically to one another. Human nature consists of greed, defiance, and pride; it also shelters traces of compassion, altruism, and high-mindedness. It’s the latter hemisphere we must draw nearer to.

In the final essay in this series, we’ll discuss Distributism, the system most promising to basic common sense and to the human conscience. We won’t rely on arguments of, “I have the natural right to x”, but we may say, “Per our traditional moral code, I am trusted with x so long as I respect my obligation to y in my fellow man.” Distributism is rational near to the point of stupidity, so virtuous as to be inconceivable. Nevertheless, as we state the facts plainly, there will be no doubt that Distributism is the Right, the just, and the ultimately good way to conduct our affairs. Whether we rise to the challenge of achieving Distributism isn’t a joyful inevitability. It will be achieved by the force of human will to secure an inheritance for our children that is spiritually life-giving and materially stable, prosperous but not gluttonous, and liberal without injustice. That is, if we ever achieve it at all.

– Michael Warren Davis

The author is a native Bostonian currently studying at the University of Sydney. He is an officer of the Australian Monarchist League. His personal blog is “The American High Tory”.

End note

- True Reactionaries (such as Joseph de Maistre) allow “legitimate” authorities—Churches, Kings, etc.—to have natural rights as political governors. Deus Vult arguments, without making a judgment of their validity, are irrelevant for the purposes of this discussion.

Editorial Note

- All caption text by SydneyTrads Editors.

Be the first to comment on "Essays on the Frankfurt School, Part IV: Natural Rights"