I

God is the “Opiate of the People”

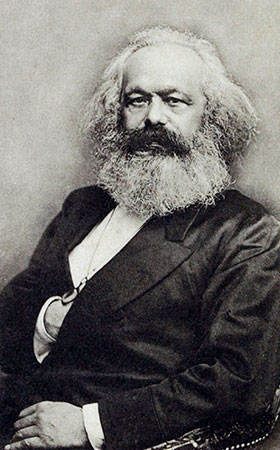

For Karl Marx, God is what he calls the “opiate of the people.” That is, belief in God is a kind of narcotic that makes man’s head hazy with irrationality. The great crime in this, as Marxism alleges, is that belief in God distracts man from paying undivided allegiance to the state.

On the other hand, Nietzsche is bothered by belief in God on metaphysical grounds. For Nietzsche, much as is the case with Jean-Paul Sartre, the world and human existence cannot be the product of a benevolent God. One reason for this is that man is a kind of cosmic joke, according to them. What kind of God would create anything, only to see it suffer and decay, if it possesses higher consciousness? What is the point of creation in the first place? such thinkers ask. Of course, regardless of what man knows about the existence of God, human reality appears to be governed by physical laws that we must respect or contend with at some level. The latter realization serves as part of the resentment that many secular thinkers display about human existence.

Karl Marx

Marxism abolishes the idea of personhood by diverting all human energy toward questions of the here-and-now. The state, specifically in the guise of international communism and socialism, should consume man’s passion and thought. This is what Marxists mean by optimism. Marxism’s messianism is coerced optimism. This is one way that man can be made happy. If man surrenders the idea of idle time – leisure – life will take on a level of worldly meaning and purpose that has never been possible in other historical eras. This is what “Marxist consciousness” promotes. God, Marx and his disciples contend, is the state, the perfection of which will transform man from a savage bourgeois that thinks about things like God, into developing a greater social conscience.

Nietzsche’s main philosophical preoccupation is with values. Values that seek transcendence and the sublime are concerns, Nietzsche affirms, that keep man an irrational savage. According to him, Christianity enslaves man. When God is vanished from man’s thought, Nietzsche tells us, only then are we free to face the abyss. Man must be made to look into the abyss and be able to rejoice. This, then, is one way that “what will not kill you, will make you stronger.”

Is this sadism? you might ask. For Nietzsche, it is nothingness itself that man must embrace. According to Nietzsche, man’s brief excursion into time – human existence – is enough to make the strongest people turn into gods. Hence, the aversion to the metaphysics of God in Nietzsche’s work is transformed into an attempt to become God itself. This proves to be an exercise in creating something out of nothing that, ironically, could never take place if man believes in God. Nietzsche understands belief in God to be detrimental for the will to power. Man, he tells us, must make himself into a God – or die trying – through the will to power over the self. While will to power over the self is not altogether a bad thing when coupled with other wisdom, Nietzsche destroys man’s ability to ponder and accept limitation in human existence.

Friedrich Nietzsche

Let us consider that one manner to deny that Jesus forms part of the Trinity is to destroy the notion that God exists. If, like Marx argues, man accepts that God is a fabricated concept, then other principles that follow from this cannot help but be false. Why concern oneself with the appendages of an organism, if one can just go for its heart? If the foundation of an idea, e.g., God exists as the first principle of the cosmos is false, what follows from this will have the solidity of a house of cards. As a consequence, anyone claiming to be the son of a deity that does not exist must be a lunatic who makes himself the object of ridicule. This is one of the many fashionable credos of atheism.

II

Contrived and Fashionable Atheism

Post-modern radical skepticism has made caricature assassination by way of derision a highly effective tool. Dating back to the earliest disinformation campaigns of international communism in 1917, the destruction of objective values has been a priority of militant secularism. It is naïve to think that this concentrated effort to annihilate Christian values does not benefit the proponents of the secular state. Communism is the take-over of all aspects of human life by the state. It is highly inaccurate to suggest that communism is merely an economic system. The personal character traits of communists and orthodox Christians are worlds apart. Communism is motivated by envy and resentment, not love and sacrifice, as the latter are indicative of a Christian worldview. Atheism is the official state religion of communist regimes. In communism, citizens must pledge allegiance to the state.

In the secular state religious belief is relegated to the realm of private life. In communism, this is not even an option. The communist mind understands the power of conviction that religious belief has over a person’s life. Hence, in communism belief is outright outlawed. This has the dual effect of segregating believers from the general population, in addition to suspecting dissidents of thought crimes. Techniques of disinformation are only effective when they inform all aspects of human life. Antonio Gramsci’s work asserts that if communism is to spread worldwide and forge the values of the new communist man, misinformation must take up a prominent role, especially in Western culture.

Jean-Paul Sartre

Christianity is fodder for Marxist propaganda. According to self-professed social-political revolutionaries, Jesus the man, remains a potent tool of sophistry. Like bread dough, the historical Jesus can be made out to serve the needs of many popular causes. Marxism, in all its variegated forms, exploits this.

This is why “death-of-God-theology” clings to the notion that while God, in some abstract and vague form exists, Jesus has no rightful claim to align himself with this entity. For Marxism, the historical Jesus serves as an excellent model of how to achieve Marxist praxis. Marxism is careful not to squander the cash value of the latter.

Marxism contends that is hard to conceive that men and women, through the span of over two thousand years and diverse cultures, remain interested and/or captivated by the local squabbles of Jewish Rabbi’s in Jesus’ time. The torrid squabbles between Pharisees, Sadducees and Essenes over questions of life after death, reincarnation and the details of the coming of the Messiah, as the ancient Jewish historian Josephus describes, do little to inspire devotion to Jesus. Instead, the historical Jesus can in principle be our neighbor Peter or Uncle Theodore.

If Jesus is not the Son of God, given that God does not exist, then people are free to create “theologies” of this-and-that on demand. This in itself is a powerful elixir of secular power and atheism. Nietzsche is correct that the death of God says more about man than it does about God. Post-modern man’s desire to create an ever-expansive, customized God is motivated by social-political and cultural needs. This is unprecedented in human history.

Antonio Francesco Gramsci

One way to destroy the integrity of a belief system, metaphysics and epistemology that seek to know reality is to trivialize these. Trivialization makes genuine thought and reflection on serious matters a thing of the past. It also destroys man’s capacity to express sincere and spontaneous emotion.

Can post-modernity’s contradictory theories about the nature of man, human existence and God, to cite just a few of these, truly exist on the same plane without cancelling each other out? Doesn’t man have a duty to exercise reason and allow inference to deliver us to truth, regardless of the unsavory truths that we uncover? Perhaps Nietzsche’s assertion that man cannot handle too much truth is correct.

Contemporary human existence has been trivialized, even paralyzed by the incessant zest for abstraction and theory that border on the pathological. Post-modernity has conditioned man to view all aspects of life through the prism of social-political categories. This is the true legacy of Marxism. It is no longer possible to engage in spontaneous thought and reflection. This mania for abstraction and theory is indicative of contemporary man’s inability to entertain the vagaries of unknowing. This condition has reached a negative apotheosis. Man no longer understands that human reality cannot be contorted ad infinitum to accommodate all our whims and desires. This epic neurosis now encompasses the fashionable negation of belief in God.

The recognition that we live in a universe that is not of our own creation enables us to wonder about the source of its creation. However, even this concern has suffered from reductionism, which posits that human reality has a physical-chemical foundation. This form of reductionism deals not with why, but rather how things happen. Yet existential questions are rooted in why human reality is what it is, not how. Existential man asks, why is man privy to something – being – and not nothing? This question is grounded in an existential concern for one’s own being. This form of reflection cannot originate from the outside, as spectators watching a sporting event. On the contrary, existential reflection glances inward, which consists of a subjective turn.

The recognition that we live in a universe that is not of our own creation enables us to wonder about the source of its creation. However, even this concern has suffered from reductionism, which posits that human reality has a physical-chemical foundation. This form of reductionism deals not with why, but rather how things happen. Yet existential questions are rooted in why human reality is what it is, not how. Existential man asks, why is man privy to something – being – and not nothing? This question is grounded in an existential concern for one’s own being. This form of reflection cannot originate from the outside, as spectators watching a sporting event. On the contrary, existential reflection glances inward, which consists of a subjective turn.

For reasons of methodology and personal temperament, scientists concentrate their attention on questions that have little or nothing to do with self-reflection. That is, existential concerns. The latter form of questioning informs perennial philosophy. Perennial philosophy serves as the ground of wisdom that has accumulated through much trial, tribulation and human suffering. This is one reason why man cannot reduce moral and metaphysical questions to scientific principles.

A rudimentary understanding of human history bears out the reality that before man practiced science, he already had to grapple with moral and metaphysical questions. That is, with questions of a vital nature. Man’s understanding of natural phenomenon is rooted in our desire to know how things work. Yet existential self-reflection is about the cultivation of personhood.

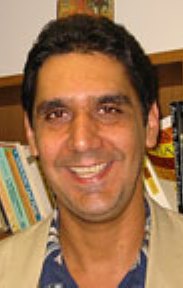

Prof. Pedro Blas Gonzalez

— Pedro Blas González is Professor of Philosophy at Barry University, Miami Shores, Florida. He earned his doctoral degree in Philosophy at DePaul University in 1995. Dr. González has published extensively on leading Spanish philosophers, such as Ortega y Gasset and Unamuno. His books have included Unamuno: A Lyrical Essay (Floricanto Press, 2007), Ortega’s ‘Revolt of the Masses’ and the Triumph of the New Man (Algora Publishing, 2007), Fragments: Essays in Subjectivity, Individuality and Autonomy (Algora Press, 2005) and Human Existence as Radical Reality: Ortega’s Philosophy of Subjectivity (Paragon House). He also published a translation and introduction of José Ortega y Gasset’s last work to appear in English, “Medio siglo de Filosofia” (1951) in Philosophy Today Vol. 42 Issue 2 (Summer 1998).

Leave a comment