Vladimir Solovyov’s insightful The Crisis of Western Philosophy can enlighten us today as to the importance of re-telling history to educate subsequent generations. With its reference to Man’s philosophical ability to seek truth, the book offers postmodern Man much needed perspective about our infatuation with collective movements that can only gain traction through coerced re-education.

Man’s history is the history of ideas. In turn, ideas originate in the thought of differentiated persons. The negation of this fundamental truth is tantamount to asserting that birds are capable of flight, not because they have wings, but because they live on a planet with wind. Solovyov explains that:

Philosophical knowledge is expressly an activity of the personal reason or the separate person in all the clarity of this person’s individual consciousness. The subject of philosophy is preeminently the singular I as a knower […] Philosophy is a separate world-view of separate individuals. The common world-view of nations and tribes always has a religious, not a philosophical character.1

I

The Importance of Re-Telling History in Lieu of the Re-Education Program of Radical Ideologues in Western Democracies

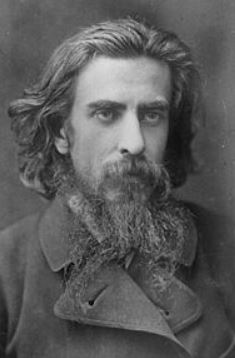

Solovyov’s contention is that philosophical vocation is incommensurate with the party-line that dictates how a thinker ought to think. Commitment to the party mentality violates the idea that the genuine man-of-letters, or what is called today the intellectual, ought to be a free thinker first and foremost.

Vladimir Sergeyevich Solovyov (b. 1853 d. 1900)

Lamentably, postmodernism has turned Western civilization into a colossal and sad re-education camp. How can truth, beauty and the moral virtues that enabled man to thrive and attain contentment in former times inform human existence in a time that asphyxiates longing for such a pathos? Intellectuals should exercise good will. What happens in the absence of good will is that man turns to political expediency, and ultimately, tyranny.

The morally vacillating and radical ideologue, Jean-Paul Sartre, is a fine example of the former. Sartre’s romantic foray into Cuban communism in the 1960s must have seem to him like a profound personal statement, given his perceived self-importance in aiding the cause of Man’s alleged universal suffrage. Sartre’s radical ideology came into conflict with his anemic moral sense. The essence of this kind of conflict was the culprit that brought Sartre’s and Albert Camus’ friendship to a halt. Sartre tells his side of the story in an article entitled “Reply to Albert Camus” that appeared in the August 1952 issue of Les Temps Modernes. Sartre’s article is a reply to a prior article by Camus entitled “A Letter to the Editor of Les Temps Modernes” that had previously appeared in that same periodical. In his merciless article, Sartre and other French communist intellectuals attacked Camus as being a bourgeois thinker. Camus criticized Sartre’s defense of the communist party, this, vis-à-vis Sartre’s embrace of Stalinism.

II

Creators of the Soviet Gulag

It seems natural that in the best interest of man’s capacity to distinguish truth from falsehood, we are periodically reminded of prime examples of the devastation that radical ideology’s nihilism brings about in human history. The latter is systematically covered up by postmodernist radical ideologues in their campaign of re-education, which emulate the slander and misinformation techniques first brought about by Lenin. The latter is now applied to all aspects of Western civilization through the social-political radicalization introduced by the crafty social-engineers of the Frankfurt School. Let’s us reflect as to what is the function of intellectuals in a totalitarian system?

Jean-Paul Sartre (b. 1905 d. 1980)

In recent times, Jürgen Habermas, the last living member of the Frankfurt School has tried to re-habilitate – save face in Asian philosophy – the Marxist ideology of the Frankfurt school, much like failing corporations often seek to re-structure the organization. Habermas’ trying to embrace metaphysics and the role of religious belief in human life in his latest work is simply a case of too little too late. The fundamental tenets of his anti-metaphysical philosophy make his social-political philosophy as rationally sound as a house of cards.

It is estimated that Stalin murdered over 1,500 writers using the resources, first of the Cheka (Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counter-revolutions and Sabotage), and later that of the GPU (State Political Administration), which was formed in 1922. These figures are based on recently declassified KGB archives that are easily accessible. This is just a conservative estimate, because in communist regimes the objective weight of data, statistics and facts disappear as quickly as its most vocal dissidents.

Albert Camus (b. 1913 d. 1960)

These pogroms took place in order for Stalin’s government to reward the writers and thinkers who promoted communism by belonging to the communist party’s union for writers. These are considered the heroes of Stalinism. This was Stalinism in-the-making; communist realism cannot tolerate dissidents. Stalinism demanded that committed writers devote their entire energy to the service of the state. Those who refused do so were considered reactionaries – intransigent at best – and were labelled enemies of the state, the alleged workers’ paradise of the new Soviet Man. This was the framework that permitted millions to be persecuted and executed. People who were alleged enemies of the state were sent to the Soviet gulag, the longest lasting and elaborate version of concentration camps. It is important to recognize that Soviet concentration camps became a vehicle of communist terror in every communist country, not just the Soviet Union. This proves how easy it is to prostitute and subvert reason to the cause of barbarity. Many Western intellectuals defend crimes committed in communist regimes as excusable, alleging ignorance of the system, or due to Western critics’ failure to understand the implications of dialectical materialism. From the outset of the October Revolution of 1917, the Bolshevik program for Russia was marked by a stringent hate for ideas, that is, genuine thought, which is apolitical.

Jürgen Habermas (b. 1929)

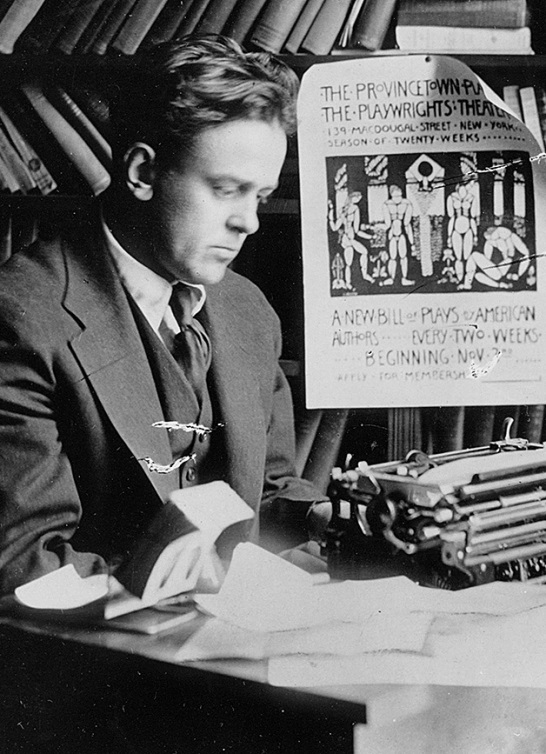

John Silas Reed, a radical American from Oregon, best known for his book about the Bolshevik takeover of Russia entitled Ten Days that Shook the World was an obstreperous Greenwich Village, rich, communist malcontent. Mr. Reed detested American democracy so intensely that he founded the American Communist Movement in 1919. For his internationalist’s loyalty, Reed was eventually rewarded by being buried in the Kremlin Wall – the same honor offered to the infamous member of the Cambridge spy ring, Kim Philby.2 In 1913 Reed was writing for a communist magazine, Masses, which was at the time edited by Max Eastman. Concerning his preference for literature, Reed has the following scathing words,

We refuse to commit ourselves to any course of action, except this: to do with the Masses exactly what we please […] we don’t even intend to reconciliate our readers […] poems, stories, drawings rejected by the capitalistic press on account of their excellence will find a welcome […] we intend to be arrogant, impertinent, in bad taste, but not vulgar […] to attack old systems, old morals, old prejudices […] to set up new ones in their places […] bound by no creed or theory of social reform, we will express them all, providing they be radical.3

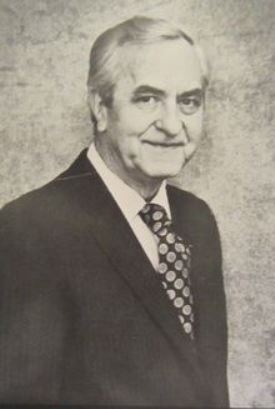

The egregious problem with this provision is that it has nothing to do with literature and everything to do with communist ideology. William Barrett, who in the estimation of many commentators, has painted one of the most in-depth and telling pictures of the hypocritical double standard of Western radical ideologue intellectuals of the Twentieth Century, explains the problem in the following way:

In politics, for example, that his own continued existence as a dissenter depends on the survival of the United States as a free nation in a world going increasingly totalitarian. If his thinking deliberately operates outside the paths of our common life, he complains that he has been alienated. In fact, in no age of history has the intellectual been more influential upon human affairs than in the modern world. Consider the intellectuals of the French Revolution: they have shaped the world we live in, and they were truants, if we may believe Edmund Burke.4

Barrett, who was a longtime Professor of Philosophy at Columbia University, writes this from a first-hand account as former editor of Partisan Review. His is an intimate portrayal of the post WWII social-political mindset of some of the leading New York intellectuals with whom he often communicated. Among these, he includes Delmore Schwartz, Mary Therese McCarthy, Edmund Wilson, Lionel Trilling and Philip Rahv. Barrett points out in his masterful work The Truants: Adventures Among the Intellectuals that his indictment of radical ideology is on the grounds that communism depended on a great part for its alleged legitimacy on the support of Western writers and thinkers. He explains:

Never mind Burke’s own politics, consider him for the moment only as an observer. He happened to be an uncommonly sharp one, and he was in a privileged position to notice the advent of this new breed of mankind – the modern intellectual. These Frenchmen whom he observed were literary intellectuals and they loved large and sweeping abstractions, often without regard to the complex inner working of the very prosaic details that make social life at all possible. My God, how they loved The People! But Burke, as an experienced parliamentarian who had been active on many bills of legislation, knew there was no such thing at all as The People: there was only a multitude of concrete groups, furriers, weavers, farmers, merchants, with sometimes quite conflicting interests, which had to be balanced and reconciled somehow or other into the actual working of society. As soon as you have replaced this concrete plurality by the abstraction of The People, you have homogenized it into the Mass – a plastic and passive dough to be kneaded at will by the dictator. You have taken the first step toward Gulag.5

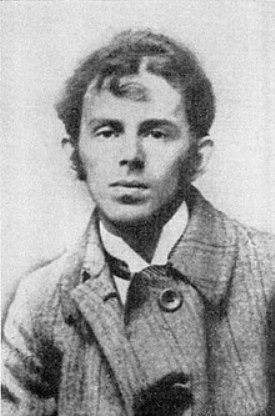

John Silas Reed (b. 1887 d. 1920)

The utility of writers in communist countries is embraced as being “engineers of the soul.” In the Soviet Union, engineers of the soul comprised the intelligentsia, which was responsible for creating the new soviet man, a subservient entity who was forged with a hammer and the butt of a bayonet. Intellectuals are invaluable to communist countries because that system receives its alleged legitimacy in the eyes of internationalists, through propaganda and misinformation that is aimed at destabilizing Western democracies.

Terror is communism’s main weapon of mass control. In order to create terror for its citizens and abroad, an elaborate mechanism of lies, the re-writing of history, re-education and brainwashing is necessary. This is why intellectuals are immensely useful in communist countries. Useful writers make a pact with the devil. Intellectuals who place their services at the mercy of the terror state find this to be their way of contributing to communist countries. They are rewarded in a degree that they would never enjoy in a democratic open society.

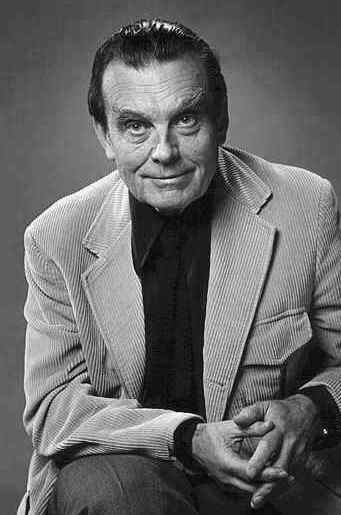

William Barrett (b. 1913 d. 1992)

In the Soviet Union, other Eastern Bloc nations and throughout the communist world, the list of writers who criticized the government, and who were persecuted for it is quite extensive. Western intellectuals cannot imagine the crude reality of the fate of dissidents in communist countries. From being ostracized by family and at work, to imprisonment, torture and execution, these individuals perished while other intellectuals enjoyed the rewards offered by the state to collaborators. Those who were released back into society from prison underwent the humiliation of being sent to re-education camps for their alleged crimes against the state. The immorality of placing a thinker or any dissident on trial because of their unwillingness to be used at the mercy of murderous regimes is unimaginable to people who live in open societies.

Prisoners in open and democratic societies are common criminals. In communist countries, political prisoners are those who oppose the one-party system. People are signaled out as political prisoners not for delinquent activities, but because in communist countries no aspect of human life can be allowed to remain un-political. The reality of total politicization of life in communist countries remains baffling to people who live in democratic societies and have lived in communist countries.

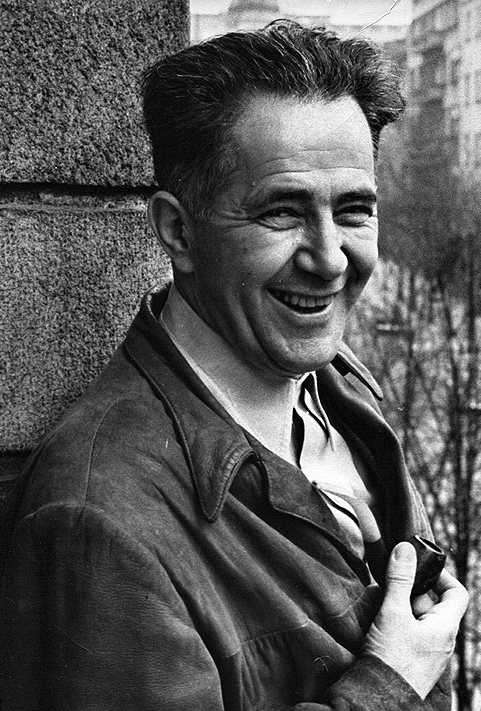

Boris Pasternak (b. 1890 d. 1960)

This is an aspect of communist ideology that was first introduced to Western democracies by Marxist intellectuals of the Frankfurt School in the 1930s, and on a massive scale beginning in the late 1960s. Gathering strength throughout the last sixty odd years, today this very same politicization of all aspects of life in open societies – in the form of political correct censorship – is the foremost threat to the continual stability of Western democracies. With its sinister campaign of re-education for political opponents fully in place today, political correctness has converted the liberties enjoyed in open societies into the same spiteful double morality practiced in communist countries. The censorship of political correctness creates distrust and cynicism among citizens in Western democracies.

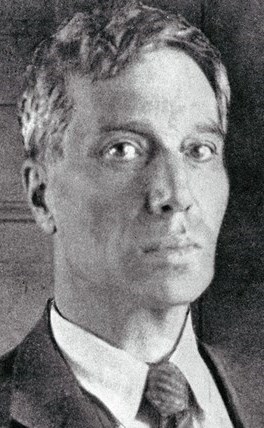

We need only to mention a few of the writers who have been victimized by communism to begin to witness the scope of this human tragedy. Among these outstanding writers and thinkers, we encounter Boris Pasternak, writer of the monumental novel Doctor Zhivago, who was expelled from the Union of Soviet Writers and forced to publicly renounce his Nobel Prize in 1958.

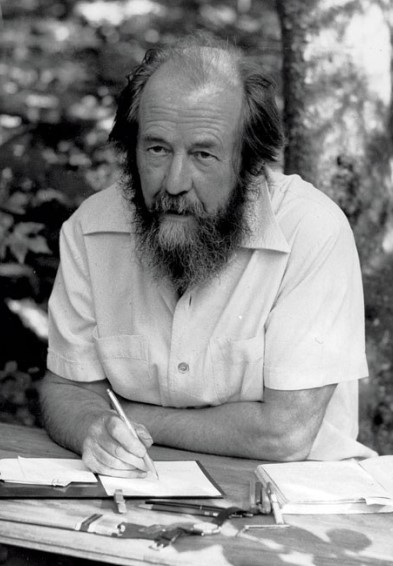

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (b. 1918 d. 2008)

We have also witnessed the well-known case of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, a writer who had to immigrate to the United States after being deported to Germany in 1974. Solzhenitsyn’s books Cancer Ward and The Gulag Archipelago have helped to open the eyes of people in Western democracies to the horrors of Soviet communism. Solzhenitsyn served with the Red Army in World War II, but was later arrested and imprisoned from 1945 to 1953 for criticizing Stalin. Solzhenitsyn is a fine example of one who was re-habilitated in 1956. One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich is his account of life as a political prisoner – the gulag – in the Soviet Union.

Still today, there are many Western intellectuals who continue to defend the legacy of communism by alleging that the former communist countries were not Marxists at all. This is a last-minute effort to separate themselves from the aberrant failures of communism and its many postmodern variant forms.

Yevgeny Ivanovich Zamyatin (b. 1884 d. 1937)

Most importantly, we must recognize that denial is a central component of the dialectical mechanism of Marxism. By negating its prior stage of development, Marxism continually remakes itself. It remakes itself without shame in light of the colossal available data against the communist system. Marxism decries that a new and much improved Marxism is to be unveiled. This informs the notorious Soviet five-year plans. In other words, the triumphs of Marxists thought and logical outcome in practice is measured in an infinite series of five-year plans that, by design, are impossible to fulfill.

Alleging that Marxism necessitates further theoretical framework, the framers of this radical ideology do not act in the best interest of the common man, but instead for the sinister and self-serving implementation of their radical theories and power. We can compare this to a scientist who refuses to abandon previously tried, erroneous and self-contradictory theories that cannot be worked into the scheme of human reality. People who do not understand or know how to identify sophism in postmodernity will not recognize the latest embodiment of radical ideology in our time. This is the great danger today for Western open societies. This is why re-education has made the inroads that it has achieved in Western democracies.

To this day, we continue to encounter profound ignorance by intellectuals of the crimes against humanity perpetrated by communism. This has occurred because of the incessant desire to lessen the evils of communism by intellectuals who have too much time and reputations invested in Marxism.

III

Writers and Dystopia

Let us turn to the dystopian novel’s depiction of social-engineering and communism. We is a classic example of the futuristic novel – what is also known as a dystopia or anti-utopia – written by the ingenious Yevgeny Zamyatin. With a striking and visionary clarity best reserved for sages, Zamyatin was able to anticipate the future of the Soviet Union under Stalinism. It is from this novel that the British writers Aldous Huxley and George Orwell received their inspiration to write Brave New World, Animal Farm and 1984 respectively. Both men admit having read Zamyatin before beginning to write the novels for which they are best known. Zamyatin’s We is less known today than other famous dystopias because its author lived behind the Iron Curtain.

Osip Mandelstam (b. 1891 d. 1938)

Zamyatin’s work is interesting because, like other free-thinking writers in communist countries, he had to resort to allegory to tell his tales and not bring onto himself the wrath of communist-party officials. Originally a supporter of the October Revolution, the tone and themes of his writing would increasingly demonstrate greater antipathy for censorship. After the publication of We in 1927, he was no longer allowed to publish.

Let us keep in mind that the thinker who devotes himself to the service of any government does so entirely by offering his soul, body and mind. Zamyatin was accused of being a bourgeois intellectual. The reason for this accusation was because he would not conform his ideas to the official Soviet government. The charge of bourgeois intellectual is a laughable term, given our knowledge of the vast support that communism has received from Western intellectuals. Communism owes a debt to the leisure and vital energy of Western intellectuals, a bourgeoisie that embraces an egotistic form of self-loathing.

Czesław Miłosz (b. 1911 d. 2004)

Of the many Soviet poets who were critical of Soviet communism, we should mention Yevgeny Aleksandrovich Yevtushenko, Andrei Andreyevich Voznesensky and Nikolai Alekseevich Klyuev. Soviet philosophers, most whom embraced Marxism early on, with the notable exception of Ayn Rand, we must mention Nikolai Alexandrovich Berdyaev, Mikhail Afanasyevich Bulgakov and Peter Berngardovich Struve. These thinkers were attacked by the Soviet apparatchik and labeled as idealists. Idealism, as Lenin explained, was anti-materialism. These thinkers were also accused of being metaphysicians – this philosophical position, as Friedrich Engels understood it merely meant to be anti-dialectic.

We must also cite the tragic fate of Osip Mandelstam, the poet and essayist who was arrested for writing Stalin epigram, and died en route to one of the many Soviet gulags. He argued that Russia was the only nation that took poetry serious enough to murder poets: “Only in Russia poetry is respected – it gets people killed. Is there anywhere else where poetry is so common a motive for murder?” His wife, the writer, Nadezhda Mandelstam, chronicled Osip’s odyssey in her book Hope Against Hope.

IV

Why Gulags will Never Disappear: The Totalitarian Impulse

To truly understand the ethos and pathos of individuals who embrace tyranny, it is necessary to understand how these individuals foment envy and resentment, thus allowing for the creation of a social-political system that systematically pins people against each other: communism and socialism.

Milovan Đilas (b. ? d. 1995)

One of the most insightful thinkers to shed light on the plight of individuals in communist countries is the Polish writer Czesław Miłosz. Mr. Miłosz’s The Captive Mind is a book that explains in great detail what communist regimes do to writers who are opposed to communist realism. This is a work that probes the psychology of the totalitarian impulse, much as is the case with Camus’ The Rebel.

The Captive Mind is similar in its philosophical analysis of the cunning utility of communist control that the Yugoslav writer, Milovan Đilas, points out. In Conversations with Stalin, Đilas offers an astute window into the mindset of Stalin, Molotov, Krushchev and Tito, to name just a few communists leaders. Equally impressive in depth and acumen are his two other classic works The New Class and his autobiographical depiction of his youth, Land without Justice. Đilas ends this work with an indictment of Stalin that is prophetic of the rise of communism:

The forces that swept him forward and that he led, with their absolute ideals, could have no other kind of leader but him, given that level of Russian and world relations, nor could they have been served by different methods. The creator of a closed social system, he was at the same time its instrument and, in changed circumstances and all too late, he became its victim. Unsurpassed in violence and crime, Stalin was no less the leader and organizer of a certain social system. Today he rates very low, pilloried for his “errors,” through which the leaders of that same system intend to redeem both the system and themselves.6

Stanisław Witkiewicz (b. 1851 d. 1915)

In Poland, we also find the genius that was Stanisław Witkiewicz (aka “Witacy”), painter and author of Insatiability, a novel that mocks cure-all radical ideological systems of government that achieve their sinister results by administering to its citizens the murti-bing pill. In Insatiability, Witkiewicz, like Zamyatin, posits the reality of a world where everyone is coerced into happiness. The great selling point of communism, Witkiewicz realized, is the alleged mass distribution of happiness. What was before seen as the realm of God is now egalitarianism forged with an iron fist. Witkiewicz wrote two manifestos of aesthetics and writing entitled New Forms in Painting and Introduction to the Theory of Pure Form in the Theatre. Witkiewicz committed suicide 1939 due to the encroaching Soviet invasion of Poland, which he foresaw.

In the former Czechoslovakia, after the Soviet invasion of 1968, we witness more of the same with the arrest of Milan Kundera and other writers. Kundera depicted the tragedy of the communist system in his 1967 novel, The Joke. He eventually immigrated to France in 1975. Also, in Czechoslovakia, Václav Havel was a dramatist and philosopher who was frequently arrested, including in 1977, when he formed the dissident group Charter 77, and in 1979, after the Velvet Revolution, when he was incarcerated for four and half years for being a subversive. Mr. Havel was elected President of the new republic through popular vote – from 1989 to 1992 – after the overthrow of the Czechoslovakian Communist Party in 1989. Havel was concerned that postmodern Man knows increasingly less and less about the meaning of his own life, and cares even less about it.

Milan Kundera (b. 1929)

In China, the central committee has victimized its citizens, especially writers, since the Communist take-over of 1949. Given that the central preoccupation of the totalitarian impulse is quantification as production, rather than respect for persons, writers, thinkers and artist who do not tow the communist line are ostracized as persona non grata: people who block the progress of the state machinery. If these entities cooperate in becoming useful to the communist party, then they are rewarded handsomely with material goods and prestige by the ruling elites. This is still the case today. Gao Xingjian (高行健), the 2000 Nobel Prize winner in literature, is a perfect case in point. Xingjian was awarded the Nobel Prize by the Swedish academy for “the bitter insights and linguistic ingenuity in his writing about the struggle for individuality in mass culture.”7 Xingjian, like so many other faceless, nameless writers had to burn his writings during Mao Tse-Tung’s 1966-76 Cultural Revolution in order to remain alive due to their content, which was critical of the regime. About his books, which have not been available in China after his being expelled from the country of his birth, Mr. Xingjian writes,

In China, I could not trust anyone, not even my family. The atmosphere was so poisoned, people were so brainwashed that even someone from your own family could turn you in.8

Gao Xingjian (高行健) (b. 1940)

Communist Cuba has been of particular interest to communist and Western leftist intellectuals because of the lure of what leftist intellectuals consider its exotic dimension. The third world continues to exist as a feel-good source of excitement for bourgeois radical ideologues of all stripes. Like Sartre, Western academics have found Cuba’s proximity to the United States their rallying point to cheer on Cuban communism. The main interest that Cuba has possessed for writers and bourgeois radicalized academics has been its opposition to the United States. Thus, proving the adage that the enemy of my enemy is my friend. Intellectual hypocrisy has exploited the Cuban people in a manner consistent with the same old-world bigotry that postmodern progressives today deride as racism.

While Cuba was a satellite of the Soviets, it was a de facto colony of the new colonization that was Soviet imperialism. These are fine details that radical intellectuals manage to occlude. It is also an undying testament to the religious fervor that is a central aspect of the psyche of radical ideologues.9 In Cuba, the role of the intellectual is often played out in secrecy through sheer survival instinct, much the same as in eastern bloc and other Soviet satellite regimes. It is a well-known fact that the Cuban Direccion General de Inteligencia (DGI) was set-up and controlled by the Soviets under the direction of General Viktor Simenov. In Cuba, the Bulgarian Darjavna Sigurnost (Държавна сигурност), one of the most ruthless terror organizations in the world, as well as the East German secret police, the infamous Stasi (Staatssicherheitsdienst), played an instrumental role in training the Cuban secret police. Intellectuals in Cuba are mere puppets of the central committee for the defense of the revolution. In other words, whoever opposes the official communist government line is committed to a life of endless suffering in the form of harassment, unemployment, imprisonment or firing squad.

Reinaldo Arenas (b. 1943 d. 1990)

Reinaldo Arenas, the exiled emerging Cuban writer, came to the United States in 1980 and testified to the international community about human rights violations in Cuba. Arenas (1943-1990) is the writer of Celestino antes del alba, (Celestino Before Dawn), a novel written in 1967 that is critical of the Castro regime, as well as El mundo aluciante (Hallucinations) and El color del verano (The Color of Summer) among other books. Arenas was placed in a re-education camp, later imprisoned and had his works banned on the island. Arenas’ novel Antes Que Anochesca (Before Night Falls) was turned into a motion picture. Another well-publicized case of a Cuban writer who has been victimized by communist tyranny is that of Maria Elena Cruz Varela, a woman who spent many years in prison for her work. Mrs. Varela is the writer of the novel Dios En Las Carceles De Cuba (God In the Prisons of Cuba). She currently lives in exile.

Maria Elena Cruz Varela (b. 1953)

It is also important to recognize that Cuba has thousands of political dissidents, many who have attempted to practice independent journalism, others who are imprisoned for their desire to establish what is called the Free Library Movement that enables neighbors to exchange books with each other. These grotesque offenses against humanity are taking place in the twentieth first century – in the age of the Internet.

We ought also to be reminded of the murder of Bulgarian novelist and playwright, Georgi Ivanov Markov, in London in 1978. Markov was a marked man by communist secret agents since his defection in 1969. He was sentenced in absentia for six and a half years for this act, which communist authorities considered an act of treason. Markov was guilty of slandering comrade Zhivkov, the then Bulgarian dictator.

As a journalist for the BBC World Service and Radio Free Europe, Markov criticized Bulgarian communism. Unfortunately, his death has passed on to resemble a novel of espionage in its method and technique of intrigue. While waiting for a bus near the edge of the river Thames, Markov was bumped from behind by a man who dropped his umbrella in the process. He then felt a stinging pain on his leg throughout the day. Later that evening the pain became intense and coupled with fever. That night Markov was admitted into a hospital, where he died three days later. Markov had been poisoned. The man carrying the umbrella jabbed him with a tiny pellet of platinum and iridium.10

Ioan Petru Culianu (b. 1950 d. 1991)

A similar case is that of Ioan Petru Culianu, a professor of History at the University of Chicago, who was murdered in a restroom stall of that same department in 1991. Culianu’s case reminds us of the contempt that communist ideology holds for thought and free thinkers. Culianu, as well as his compatriot, the historian of religion, Mircea Eliade, who encouraged Culianu to come to the University of Chicago were proponents of the values fostered by an open society. Culianu, an exiled Romanian was a strong critic of the Ceausescu regime, until a member of that governments’ secret police – the Securitate – silenced him with a single shot from a .25 revolver. The murder took place after the official fall of communism.11

I conclude by suggesting that conscientious thinkers must be guided by sincere respect for truth and rational discipline. The open society can guide the existence of its most receptive citizens into lives of freedom, dignity and the ability to cultivate their moral worth as persons. The exercise of virtue serves to set a good example for citizens of the open society. Virtue empowers people into leading meaningful lives. It is concern for the welfare of the individual that makes the best leaders, not radical ideology. Let us keep in mind that politics, as Aristotle believed, is the art of governing – well.

Prof. Pedro Blas Gonzalez

— Pedro Blas González is Professor of Philosophy at Barry University, Miami Shores, Florida. He earned his doctoral degree in Philosophy at DePaul University in 1995. Dr. González has published extensively on leading Spanish philosophers, such as Ortega y Gasset and Unamuno. His books have included Unamuno: A Lyrical Essay (Floricanto Press, 2007), Ortega’s ‘Revolt of the Masses’ and the Triumph of the New Man (Algora Publishing, 2007), Fragments: Essays in Subjectivity, Individuality and Autonomy (Algora Press, 2005) and Human Existence as Radical Reality: Ortega’s Philosophy of Subjectivity (Paragon House). He also published a translation and introduction of José Ortega y Gasset’s last work to appear in English, “Medio siglo de Filosofia” (1951) in Philosophy Today Vol. 42 Issue 2 (Summer 1998).

Endnotes:

- Vladimir Solovyov, The Crisis of Western Philosophy: Against the Positivists Boris Jakim (trans., ed.) (Hudson, New York: Lindisfarne Press, 1996) p. 13.

- Philip Knightley, The Master Spy: The Story of Kim Philby (New York: Vintage Books, 1990) p. 263. The author writes: “Wheatcroft argues eloquently that Philby and his ilk were power worshippers. He says they must have known the nature of the murderous dictatorship of Lenin and Stalin and yet they continued to believe it. Why? He says that, like any religious faith, communism required a suspension of belief, but that blind credulity could not be the whole answer because men as intelligent as Philby, Burgess, Blunt and their like could not fail to notice the truth.”

- John Reed, Ten Days That Shook the World V. Lenin (fwd.) (New York: Vintage Books, 1960) p. xix.

- William Barrett, The Truants: Adventures Among the Intellectuals. (Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor Books, 1979) p. 13.

- Ibid. p. 14.

- Milovan Djilas, Conversation with Stalin Michael B. Petrovich (trans.) (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., New York, 1963) p. 191.

- Vide: M. August. Associated Press (13 October 2000).

- Ibid.

- James Monahan and Kenneth O. Gilmore, The Great Deception: The Inside Story of How the Kremlin Took Over Cuba. (New York: Farrar, Straus and Company, 1963).

- Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB (New York: Basic Books, 1999). Andrew explains: “The KGB eventually became embroiled in DS special political actions. Early in 1978 General Dimitar Stoyanov, Bulgarian interior minister and head of the DS, appealed to the Centre for help in liquidating Georgi Markov, then living in London and accused of ‘slandering Comrade Zhivko’ in his many radio broadcasts. The request was considered at a meeting chaired by Andropov and attended by Kryuchkov, Vice Admiral Mikhail Usatov (Kryuchkov’s deputy Oleg Kalugin, head of FCD counterintelligence). Though reluctant to take the risks involved in helping the Bulgarians, Andropov eventually accepted Kryuchkov’s argument that to refuse would be an unacceptable slight of Zhivkov. ‘But,’ he insisted, ‘there is to be no direct participation on our part. Give the Bulgarians whatever they need, show them how to use it and send someone to Sofia to train their people. But that’s all.’ The Centre made available to the DS the resources of its top-secret poisons laboratory, the successor to the Kamera of the Stalinist era, attached to the OUT (Operational Technical) Directorate and under the direct control of the KGB chairman. Sergei Mikhailovich Golubev, head of FCD security and a poison specialist, was put in charge of liaison with the Bulgarians. The murder weapon eventually chosen was concealed in an American umbrella, one of a number purchased at Golubev’s request by the Washington residency in order to disguise the KGB connection if the weapon was ever discovered. The tip was converted by OUT technicians into a silenced gun capable of firing a tiny pellet containing a lethal dose of ricin, a highly toxic poison made from castor-oil seeds. On September 7, 1978, while Markov was waiting at a bus stop on Waterloo Bridge, he felt a sudden sting in his right thigh. Turning instinctively, he saw a man behind him who had dropped his umbrella. The stranger apologized, picked up his umbrella and got into a taxi waiting nearby. Though Markov felt no immediate ill effects, he became seriously ill next day and died in hospital on September 11. During the autopsy a tiny pellet was recovered from Markov’s thigh, but the ricin, as Golubev had calculated, had decomposed.” pp. 388 to 389.

- Ted Anton, Eros, Magic, and the Murder of Professor Culianu (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1996).

Dear Sir/Madam

Thank you indeed for this post. Prof Gonzalez had produced a thoughtful and important piece. I am much appreciative.

Please keep up the good work. I keep a separate file for my Sydney Trad material!

Yours faithfully

Dr John J Coe