This is the text of a presentation given to the Sydney Traditionalist Forum on 27 September 2019 by Prof. Barry Spurr, as part of the Forum’s “Quarterly Inquiry Series”.

♣

In a recent interview, Peter Hitchens spoke of the “post-revolutionary” state of Western Civilisation. Unlike world upheavals in the European past, such as the Reformation, the English Civil War, the French Revolution, the Bolshevik uprising of 1917, world wars of the twentieth century , the violent incursions of Fascist and Communist totalitarianism, he noted that this late twentieth-century revolution has not been marked by pitched battles in the streets, with victors’ flags planted on city halls or commissars goose-stepping through communities. The outward and visible signs have not been so apparent. And it is unlike such intellectual revolutions as the mid-Victorian crisis of faith, of which, to varying degrees, most intelligent people were aware and which excited protracted and informed debate and came to influence the lives of multitudes.

The cultural revolution in our time – what Douglas Murray argues has facilitated “the strange death of Europe”, a form of cultural suicide on a massive scale – has been even more wide-ranging, but has taken place in a fashion that is not only non-violent, but in its subtle, yet ever-ramifying progress (often inconspicuous, and all the more insidious for being so) has achieved a rigorous and sustained subversion of nothing less than the entire heritage and values of Western Civilisation.

Peter Hitchens

One thinks of that notorious white-anting that can occur in an even solid and sound-appearing house, which is not identified by the owners until it is far too late, and the structure collapses.

The revolution in Western culture is now emerging in plain sight, in every dimension of public life: in government, the law, the media, and principally and most strategically, through the takeover of all levels of the education system, but especially the universities. Hitchens contends that, in spite of all this evidence, most people today still remain incompletely aware – or perhaps in a state of denial, or a sense of helplessness – that it has happened.

Certainly, they were insufficiently aware of this revolution in its early stages, in the aftermath of the counter-cultural upheavals of the 1960s. I can remember senior university people saying in the 1970s that one needed not to concern oneself over-much about the revolutionary spirit on campus, most evident in the Humanities. Its possible ongoing, lasting and very damaging consequences should not, they contended, particularly bother anybody – although even catastrophists, then, could not have imagined, in their wildest dystopic nightmares, how thorough-going the wrecking process would turn out to be, half a century later. These blinkered sages argued that, like a pendulum, the extremity of the initial stages of this white-anting of the institutions would slowly swing back to the sensible centre.

Not wanting to present myself as overly wise before the event, in my salad days, I must nonetheless say that I found this argument utterly unpersuasive then. The following decades of the destruction of the university – “the academy is dead”, according to Hitchens – have more than justified that youthful scepticism. How grimly amusing it is to read, now, that at least some commentators are waking up to the colossal damage that has been done by this revolution; more and more articles are appearing that proceed from the wondrous epiphany that their writers have had that something appears to be seriously amiss in such as our educational establishments, our fake-news-peddling media and our so-called justice system. Have they been asleep for the last fifty years? If only they had discerned this at least a generation ago, the possibility of resistance to or reclamation of what was being progressively, systematically undermined and disappeared might have been possible.

Douglas Murray

Now, the barbarians are not only within the gates, but have been in charge for years, and as many of their leaders are invariably of the Baby Boomer vintage, and, so, are on the brink of retiring from their careers of destruction, they have made it their astute business, for decades, to secure the succession of their destructive hegemony through the appointment and promotion of their creatures – a crucial aspect of what Michael Warby calls the “feral managerialism” that has now overtaken the Australian university system (for instance). These can be counted upon to sustain and continue the triumph of the revolution which has now reached such a point of lunacy, Hitchens’s “comedy of morons”, that one can only stand by in astonishment at its success.

One of the most spectacular casualties of the revolution has been the destruction of the disciplinary character of various academic subjects, such as English Literature (which I have written about in detail in Reclaiming Education, edited by Catherine Runcie and David Brooks, published last year). What I want to focus on now is a specific element – poetry – in this lamentable tale of cultural suppression, but which has larger consequences beyond merely academic or even broadly educational considerations, and going to the heart of the matter of the enrichment of human beings’ lives: intellectually, emotionally, spiritually.

What future can there be for great poetry, which was both formed by and expressed the Western mind in its finest linguistic manifestations, in this post-revolutionary environment? How can it survive in an intellectual Siberia of mandated thought, Warby’s “punitive conformity”, that is not merely utterly unreceptive to it, but determinedly opposed to it and committed to destroying its reading and appreciation, either by suppressing it entirely or so perverting its meaning and inculcating such grotesque misreading of it, as to advance revolutionary principles and annihilate any possibility of the informed appreciation of the worldview which it mirrors? More positively, it is worth considering what role poetry might conceivably play in providing some nourishment for those deprived of cultural, intellectual and spiritual sustenance, once the fruits of an education in the Humanities; what those of us reared in the now dear, dead days beyond recall when the appreciation of the glories of our civilisation in its literary expression (and in other forms, of course, such as music and art) regarded not as the work of the Devil of white supremacy and the patriarchy, but a worthy lifetime’s study, appreciation and joy.

Certainly, through the ages, the poets have prophesied of dark times ahead, and, in the early twentieth century, the two greatest poets of that era, T.S. Eliot and W.B. Yeats, foresaw, with astonishing accuracy, the decline of the West, even if the particular ways in which it has been prosecuted beyond their lifetimes was, inevitably, beyond their imaginations. Eliot’s masterwork of 1922, The Waste Land, written in the immediate wake of the holocaust of the Great War, has as its principal theme the laying-waste of the West, in all dimensions of human life. The poem’s extended metaphor of a wasted land, where there is no hope for the future, is concentrated on the death of Europe, but focused particularly on London:

Unreal City,

Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.

Flowed up the hill and down King William Street,

To where Saint Mary Woolnoth kept the hours

With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine.

The poem closes with the speaker reflecting:

I sat upon the shore

Fishing, with the arid plain behind me

Shall I at least set my lands in order?

London Bridge is falling down falling down falling down.

In this nightmare vision, the nursery rhyme has come true, and, reviewing all that he has said in the poem before, where so many fragments of Western culture, of drama, poetry and music have been incorporated, the poet declares: “These fragments I have shored against my ruins”.

Eliot had recognised the forces which, like the hosts of Midian, were gathering around to destroy Western Civilisation in the wake of the Great War. In a much-quoted reflection at the conclusion of his essay, “Thoughts after Lambeth”, written after the report of the conference of Anglican bishops at Lambeth Palace in 1930 had been released, he argues that the bishops (whose voices still amounted to something to be reckoned with, in those days) had failed to face up to the formidable challenges that were facing the West. He warned:

The World is trying the experiment of attempting to form a civilized but non-Christian mentality. The experiment will fail; but we must be very patient in awaiting its collapse; meanwhile redeeming the time: so that the Faith may be preserved alive through the dark ages before us; to renew and rebuild civilization, and save the World from suicide.

We have now entered those suicidal Dark Ages.

Eliot’s friend, Yeats, although more Romantic and heterodox in religious belief than the Classical and orthodox Eliot, expressed the same grim prognosis for Western Civilisation in his poem, ironically entitled ‘The Second Coming’ and written in the same years as The Waste Land. Yeats is thinking of three extraordinary upheavals: the Great War, the Bolshevik Revolution and – closer to his home – the Irish Easter Uprising of 1916:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

The difference today, a century on, is that these prophecies of the future have now come true. Hitchens’s view that we are now in the foothills of a catastrophe and Murray’s argument, in his latest book, The Madness of Crowds, delineate aspects of this concentrated decimation of the West and its heritage.

It is entirely predictable, in these circumstances, that the teaching of the intelligent appreciation of poetry – any poetry, let alone the once-canonical pieces written by such as the dead white males I have alluded to – is now decidedly on the nose. This is because poetry is the least susceptible of the literary arts to be stretched on the Procrustean bed of ideological correctness. You can fiddle with drama as much as you like, even dramatic poetry, and, indeed, that of its master, Shakespeare himself. Indeed it is now incumbent on directors to do so. To mutilate the text, serve it up like chopped salad, as a reviewer of a local production of one of the tragedies recently noted, and to have a female Julius Caesar – that would be Julia Caesar, I suppose – with a black man playing Casca. Criticise these historical absurdities, and you would be denounced as a sexist and a racist. There will be a female Hamlet, I understand, next year. Will Ophelia be a man, in this re-writing and re-imagining?

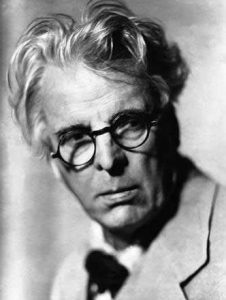

William Butler Yeats

The toxic marriage of revolutionary principles with postmodernist theory has meant that any text, in fact, that you read is available for you to read however you like – you take ownership of it. Truth being an illusion, you impose whatever ersatz-truth you like on what is before you. There is no objective meaning to be discovered – that is a fantasy – except the one you want to find there and feel ‘safe’ with. In our post-truth world, English philosopher, Sir Roger Scruton, has recently noted, all that remains once the pursuit of truth has died (as it has in the universities, to their everlasting shame) is whatever power is invested in those, fuelled by a range of resentments in a culture of repudiation, who shout the loudest, have the noisiest slogans and whose fists have grasped the levers of authority, with the consequent power to appoint and promote the compliant Elect, with their “correct” views.

[Trigger warning: the male pronoun in the following paragraph is used non-gender-specifically. Some readers may be offended] Poetry doesn’t lend itself as readily to these perversions, for the obvious reason that the entire point of reading it is to try to understand and enjoy what the poet has actually written, word-for-word, phrase after careful phrase, and the idea or emotion he is trying to communicate (as opposed to what he is not saying, and what would never have entered into his head to say) and, especially, in the course of technical appreciation of language, how he is saying it, with the precisely accurate and memorable use of vocabulary and imagery and symbols – the peculiar intensity of linguistic concentration that separates poetry from (and, in my view, elevates it above) all other forms of writing. If you start fiddling with the words, in order to bring the meaning into conformity with race, gender and class orthodoxy, then – obviously – the poem ceases to exist.

The problem in the educational domain with the heritage of poetry today, beyond its resistance to the now-customary de-mythologisation and personalising of literary texts that is pervasive in the reading of novels and drama texts, is that you only have to go to any reputable anthology of poetry in English, such as the admirable Norton Anthology of Poetry from Harvard, to find that by far the most typical contributor to this golden treasury of verse is a dead, white male. And by far the most typical subject-matter and store of references, to such as other stories and texts, and cultural memory at large, which the poets have drawn on in their own compositions, recall the main subjects, themes and values of Western Judeo-Christian history and culture, with the Bible being the most cited source – the Great Code, as Northrop Frye termed it, the single most important influence in the imaginative tradition of Western art and literature.

Prof. Keith Windschuttle

So if you have been brainwashed, as all our school students now have been for at least a generation, and from their earliest years, to believe that anything and everything from that history and tradition is not merely irrelevant to them (in the course of what historian, Keith Windschuttle has called “the killing of history” and literary scholar, Michael Wilding, “the denial of history”), but disreputable and worthless, and ripe for suppression, then the likelihood of poetry that is deeply embedded in it being given the opportunity to be heard by you, is virtually nil. As a result, we have the situation, just to take one example, in one of our leading academic schools, where the only poetry scheduled for study for the entirety of Year 9 in the English classes is an anthology of Aboriginal poetry, aptly-entitled “Deadly”. In some schools, a whole year will go by without any poetry at all being studied in English, and a term can pass without any literature of any kind at all being read. In the case of a student I know in Year 10 this year, a whole term in so-called English is looming where the sole text that has been scheduled is the latest film starring Ben Stiller.

The future of great poetry in the post-revolutionary wasteland in which we now find ourselves is the bleakest it has ever been in literary history. There was never a golden age when everybody was reading and reciting poetry and we need to remember that universal literacy only become a realisable ideal in the West during the nineteenth century. But since that time, there had been an ever-growing readership for and appreciation of poetry to the point where, in the mid-twentieth century, let us say, no-one would have considered themselves, nor any-one considered them to be a well-read and educated man and woman in an English-speaking society, such as Australia’s, who could not recite some poems from memory and who would not recognise quotations from famous works of literature, more generally, as well as from the great poets.

What is to be done about this desperate situation not only of cultural forgetting, but deliberate, enforced cultural suppression? Where can an intervention be made? The universities are a lost cause and, as historian Dr David Starkey has said, the “only way to improve education is to close all Departments of Education”. The attempt by the Ramsay Centre to plant itself in the universities to offer courses in Western Civilisation, including the Great Books, has been the futile exercise we have seen for the simple reason that a less receptive environment for what the well-meaning Centre has to offer than the contemporary universities’ Humanities departments could not be imagined.

Dr David Starkey

In our age of totalitarian Newspeak, of rampant censorship and censoriousness, poetry is being preserved in Great Books courses in various liberal arts colleges in America and at such small and elite universities as Chicago and Princeton. Regrettably, in Australia, we have never developed this tradition of small liberal arts institutions. The few of our universities that amount to anything in terms of remotely recognisable tertiary standards of entry, assessment and graduation are ever-expanding gargantuan state organisations and the one, admirable attempt to establish a liberal arts college with solid foundations in the tradition of Western Civilisation and with a Catholic emphasis, Campion College, in Sydney’s west, can hardly be described as an unqualified success and, after several years, it has not encouraged any other foundations of this kind.

It would seem that, to the extent to which the people, at large, will develop an appreciation of poetry, this will occur in spite of what happens in schools and universities, rather than because of it. In this way, it is reminiscent of the religious life and its nurturing, and much great poetry focuses on spiritual and moral experience and discernment – arguably the greatest poem in English literature, John Milton’s Paradise Lost, is a sublime and epic account of the foundational Judeo-Christian story of creation, sin and redemption. When I was an undergraduate, half a century ago, this was core reading in English Literature courses, worldwide; it has now been all but eradicated from them, and you would even have professors of English today who have never read it and certainly most graduates in English would either never have even heard of it or would have been trigger-warned off the writings of a hetero-normative patriarch who allegedly abused his succession of wives and his daughters and blamed Eve for Original Sin. The disappearance of Milton would have been unimaginable fifty years ago and this is just one example of the swift and pervasive barbaric assault that has been inflicted on our heritage. No pendulum is poised to swing back from this desolation.

My advice to those who would immerse themselves in this great tradition is to do so systematically, through the use of such as the Norton Anthology (see above), with its very helpful but not intrusive notes and accompanying essays and brief biographies of poets. People balk at such an enterprise, with the usual complaint that poetry is too difficult. Is anything that is worthwhile in life, easy? As English poet, Geoffrey Hill, has observed:

Human beings are difficult. We’re difficult to ourselves, we’re difficult to each other. I would add that genuinely difficult art is truly democratic. And that tyranny requires simplification.

Totalitarianism, as George Orwell demonstrates in Nineteen Eighty-Four, depends upon linguistic simplification and jack-booted conformity to approved speech to annihilate the thoughtcrime of deviation from mandated orthodoxy. As the anti-Nazi classicist, Theodore Haecker, wrote that what despots really like is for language to be straightforward: “Any complexity of language, any ambivalence implies intelligence”, the enemy of the totalitarian project.

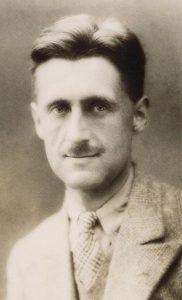

George Orwell

Even poetry that seems to be readily understandable, at first reading, can be deceptive in its simplicity. George Herbert and Emily Dickinson are good examples of this, their genius being to communicate ideas and feelings, often of the most profound subtlety, in language notable for its unusual straightforwardness of vocabulary and imagery. But theirs is a complex accomplishment that only repeated and careful readings will fully disclose. What we thought we had fully grasped becomes less clear as we re-read. Contrariwise, what seems off-puttingly complex, can with some concentrated attention, reveal its meaning and true significance and, best of all, encourage a lifetime’s enjoyment. Readers of obviously difficult poems, such as Eliot’s Four Quartets, regularly speak of the deepening of their appreciation through familiarity with the verse over the span of decades of re-reading. Such works are inexhaustible. Would we prefer a poetry – or any work of art – that offered everything that it has to offer us in our first, fleeting encounter with it? So far from deprecating the challenge to understanding, enrichment and enjoyment that poetry, through the ages, presents, we should affirm, in Yeats’s phrase, “the fascination of what’s difficult”, countering the complaint with the riposte that nothing in the history of the artistic endeavours of humanity that has been worth mastering, and coming to a deep understanding of, has been anything other than difficult. Johann Sebastian Bach’s Art of Fugue exemplifies, writes Daniel Herscovitch of the Sydney Conservatorium, “how pathos, humour, gravity, exuberance and tragedy are inextricably enmeshed in the deepest recesses of the human psyche”. Great poetry exemplifies this too, speaking of and speaking to that soul, mind and spirit.

Of all literary forms, poetry requires the most sustained concentration. In my Inaugural lecture, as Professor of Poetry at the University of Sydney, entitled (in quotation from William Wordsworth), “The Bliss of Solitude”, I referred to what I called “the three Ss”, so devalued in modern society: silence, stillness, solitude. Sociologists tell us that many people today are not merely apprehensive about these experiences, but terrified of them.

Careful reading, of any kind, requires all three of those conditions of uninterruptedness. Poetry demands them, so it is little wonder that it is so neglected today. While sustained reading of a novel or non-fictional prose is to be preferred, most of us read such prose in spells, a few chapters at a sitting, without seriously hindering our appreciation, although some kinds of prose are much more demanding than others in this way. Virginia Woolf, James Joyce and William Faulkner, for example, will yield very little in intellectual satisfaction if you dip in and out of them! But that may be because various qualities, such as the abstract character or density of their prose, approach the condition of poetry. In Woolf’s experimental novel, The Waves, for example, which she described as a “playpoem”, the complex concentration of language and thought, the subtle nuances of meaning demand our sustained attention, as does the best poetry.

So let us close with some of the greatest lines ever written. This is from the speech of Satan, in Paradise Lost, as he takes possession of Hell, the Prince of Darkness in his kingdom of darkness. In our Dark Ages, Milton’s configuration of Satan’s perverse triumph, his “bad eminence”, although written 400 years ago, rings disturbingly true of the diabolical forces abroad and apparently triumphant today:

Is this the Region, this the Soil, the Clime,

Said then the lost Arch-Angel, this the seat

That we must change for Heav’n, this mournful gloom

For that celestial light? Be it so, since he

Who now is Sovran can dispose and bid

What shall be right: fardest from him is best

Whom reason hath equald, force hath made supream

Above his equals. Farewel happy Fields

Where Joy for ever dwells: Hail horrours, hail

Infernal world, and thou profoundest Hell

Receive thy new Possessor: One who brings

A mind not to be chang’d by Place or Time.

The mind is its own place, and in it self

Can make a Heav’n of Hell, a Hell of Heav’n.

What matter where, if I be still the same,

And what I should be, all but less then he

Whom Thunder hath made greater? Here at least

We shall be free; th’ Almighty hath not built

Here for his envy, will not drive us hence:

Here we may reign secure, and in my choyce

To reign is worth ambition though in Hell:

Better to reign in Hell, then serve in Heav’n.

Prof. BARRY SPURR is the Literary Editor of Quadrant and was Australia’s first Professor of Poetry and Poetics. Professor Spurr’s numerous books and other publications cover the fields of literature, and theological and liturgical aspects of it, from the Renaissance to contemporary poetry. His best known monographs are Studying Poetry (Palgrave Macmillan, 2006) which is now in its second edition, See the Virgin Blest: Representations of the Virgin Mary in English Poetry (Palgrave Macmillan, 2007) and, most recently, ‘Anglo-Catholic in Religion’: T.S. Eliot and Christianity (Lutterworth, 2010).

Prof. BARRY SPURR is the Literary Editor of Quadrant and was Australia’s first Professor of Poetry and Poetics. Professor Spurr’s numerous books and other publications cover the fields of literature, and theological and liturgical aspects of it, from the Renaissance to contemporary poetry. His best known monographs are Studying Poetry (Palgrave Macmillan, 2006) which is now in its second edition, See the Virgin Blest: Representations of the Virgin Mary in English Poetry (Palgrave Macmillan, 2007) and, most recently, ‘Anglo-Catholic in Religion’: T.S. Eliot and Christianity (Lutterworth, 2010).

Be the first to comment on "Can Great Poetry Survive the Post-revolutionary West?"