Shostakovich’s “Leningrad” Symphony:

Art Transcending Politics

The topic is not only compound but complex, associating itself with numerous difficulties. The term transcendence, for example, is more often associated with religion and art than it is with politics. In the second decade of the Twenty-First Century, indeed, the Western nations find themselves subjugated without exception under regimes that are determinedly and explicitly anti-transcendent. The elites of these nations hate religion and beauty. They devise programs of indoctrination that condition the masses to despise religion and beauty while inducing them to adulate opinion and celebrity and to respond indulgently to the gross forms of titillation that pass for entertainment. These immanentist regimes relentlessly inculcate the super-conformity of political correctness, in adhering vehemently to which, however, the de-natured subject undoubtedly experiences physiological and psychological effects that he feels as type of ecstasy.

Gustave Le Bon (1841-1931)

Gustave Le Bon1 remarks in his study of The Crowd (1895)2 that when the suggestible individual loses himself in the irrational multitude, he enters into a mental phase “hovering on the borderland of unconsciousness” which is characterized by “violence of feeling.” It is no wonder that the crowd’s appetite should run to the insipid and at the same time to the nasty. Regimes want this result, as it increases the malleability of the masses, immobilizing them temporarily in simple satiety, while convincing them of a specious independence. Le Bon writes that, “the improbable does not exist for the crowd”,3 which falsely regards itself as a superhuman entity. Nikolai Berdyaev,4 the Russian religious thinker, agrees with Le Bon. In Freedom and the Spirit (1927),5 Berdyaev writes of the pseudo-mysticism typical of political movements in an age of crassness and materialism: “There are orgiastic types of mysticism in which the spirit is swallowed up by the ‘psychical’ or corporeal elements, and remains wedded to them.”6 According to Berdyaev, “true mysticism frees us from the sense of oppression which arises from everything which is alien to us, and imposed, as it were, from without.”7

In modernity, real transcendence is vanishingly rare while false transcendence is a common – one might say the commonest – occurrence, existing in many only slightly varied and equally jejune forms.

Berdyaev, who began as an aesthetician, before he became a theologian, frequently comments on the relation of art to transcendence or to mysticism. In The Meaning of the Creative Act (1916),8 Berdyaev turns his attention briefly to music, noting that, like everything else in modernity, music has become banal and purely functional, giving what he calls “illusory transport to another world,” while being in subservience to the empirical order. It is the case nevertheless that “in the spirit of music there is prophecy of incarnate beauty yet to be.” Berdyaev intuits, for example, that “Beethoven was a prophet”; by contrast Alexander Scriabin, who made himself out to be a vates and a mystagogue, succeeds only in articulating “a sense of foreboding and unconquered chaos.”9 Berdyaev likes to write in propositions. Thus, “the creative act of the artist is essentially the non-submission to this world and its distortions”; and “the creative act is a daring upsurge past the limitations of this world into the world of beauty.”10 Because “the artist believes that beauty is more real than the distortion of the world,” it follows that “there can be no art without an impulse to beauty.”11 In the Twentieth-Century phase of modernity, the situation has become extremely acute. In this phase, “the mechanical civilization… reducing everything to one level, depersonalizing man and depriving him of value” has led to a condition of “pseudo-being, illusory being, being turned inside out.”12

Nikolai Berdyaev (1874-1948)

Until the ideological governments of the last twenty-five years in Western Europe and North America, the most ardently anti-transcendent regimes were those of the Communist polities, whose model first imposed itself in Russia in the form of the Soviet Union after the coup-d’état of October 1917. The Leninist state was totalitarian: Its committees strove with implacable fanaticism to take in charge every aspect of the conquered and humiliated society. This Gleichschaltung of everything with the state included the arts, which in turn included music. The commissars immediately imposed the categories of the “bourgeois” and the “revolutionary” on the arts, making of the former an anathema and making of the latter a formula to which all artistic production – for everything under Communism is “production” – must conform. In August of 1934, at the All-Union Congress of Writers, with novelist Maxim Gorky as figurehead, the formula underwent Stalinist reformulation as the new code of “Socialist Realism.” Although the Congress confined itself nominally to literature the prescription implied a wider application to the totality of the arts. (How could it not?) The official bulletin of the occasion13 states how – the “representatives of almost all nations inhabiting the Soviet Union” having spoken during the event and having “raised literary problems in their own way” – a unifying theme had emerged from the voluble so-called diversity: “The cause of socialism.” The same document celebrates the victory of Socialist Realism over what it calls “formalism” and “the upholders of formalism among us.” Formalist art is “art without content,” the “reflection of rottenness and decay of the bourgeois world.” Socialist-Realist artworks by contrast must be “so fashioned that the mass reader can understand them.”

The restrictions of the Socialist-Realist mandate had already extended themselves to music explicitly through the establishment of the journal Sovietskaya Muzyka in 1933, the editorial strictures of which found reinforcement in the decrees of the Congress of Writers. Writing in Music and Musical Life in Soviet Russia 1917-1970 (1972),14 Boris Schwarz notes how, under the barely disguised existential threat, “advanced composers turned conventional, and conventional composers became commonplace.” The desideratum of any composer hoping to keep his position in the planned economy of the ideological state was to become “inoffensive”; he achieved this goal by conforming to the “new respectability” in the arts.15 Schwarz quotes from the first number of Sovietskaya Muzyka, where the editors of the journal set it forth that “the main attention of the Soviet composer must be directed towards the victorious progressive principles of reality, towards all that is heroic, bright, and beautiful.”16 As Igor Stravinsky (1882 – 1971), who grasped keenly the entanglement of politics and the arts in his native country, pointed out in the fifth of his Norton Lectures of 1939, “The Avatars of Russian Music”: “The Marxist theory that maintains that art is only a ‘superstructure based on the conditions of production’ has had a consequence that art in Russia is nothing more than an instrument of political propaganda at the service of the Communist Party and the government.”17

Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971)

Stravinsky, who perhaps read Berdyaev, makes an observation apropos Russian music that runs parallel to many an observation made by Berdyaev himself on Bolshevism’s relation to authentic culture whether in Russia or anywhere else. Ideology pretends to rationality, but invariably encumbers itself with contradictions and unprincipled exceptions. Insofar as the Revolution constitutes an assault on actual Russian culture, including Orthodox Christianity, in the dispensation of which the Russian polity anciently founded itself, the ideology that the Revolution propagates, far from organizing creative activity within a legitimate speculative system, only creates spiritual chaos and creative sterility. It is, moreover, not of the people in the least, but rather deracinated and anemic – belligerently abstract and anti-human. Thus, “without a speculative system, and lacking a well-defined order in cogitation, music has no value, or even existence, as art.” This will be so, as Stravinsky adds, because “art presupposes a culture, an upbringing, an integral stability of the intellect, and Russia of today [1939] has never been more completely devoid of these.”18

In such remarks, Stravinsky reveals himself as a respectable analyst of political modernity in its relation, or opposition, to creativity and art. Concerning the Soviet musical scene in the 1930s and 40s, however, Stravinsky undoubtedly misinterpreted certain features. In the case of the Leningrad composer Dmitry Dmitrievich Shostakovich (1906 – 1975), for example, Stravinsky could not penetrate beyond the rhetoric of Soviet musical propaganda. Stravinsky is aware of the Soviet journalistic celebration of Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony (1937),19 which carries the ominous subtitle “A Soviet Composer’s Response to Just Criticism,” but he takes its verbiage, in a review of the premier performance written by Alexei Tolstoy, at face-value. For Tolstoy, the score’s Scherzo “reflects the athletic life of the happy inhabitants of the Union.”20 In regard to Tolstoy’s fatuous periphrasis of Shostakovich’s score, Stravinsky’s indignation claims justice. The review is, as Stravinsky characterizes it, “a consummate masterpiece of bad taste, mental infirmity, and complete disorientation in the recognition of the fundamental values of life.”21 But what about Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony, in its actuality?

Alexei Tolstoy (1883-1945)

The Fifth Symphony is the direct precursor-score of the Seventh or “Leningrad” Symphony (1942),22 the Sixth (1939)23 being something of a detour in the composer’s symphonic trajectory. (The Sixth’s asymmetrical structure implies that Shostakovich abandoned the score without supplying the large-scale Finale that would have balanced the first movement.) The story of the Fifth, which still figures in the books as the exemplary Soviet Symphony, an affirmation of Communist legitimacy, is relevant to the story of the Seventh. In 1936, the Soviet musical establishment registered its displeasure with Shostakovich’s Fourth,24 which had been in rehearsal with a public performance imminent. The charge was a familiar one: “Formalism.” Given the increasing ferocity of Stalin’s police-state, the composer prudently withdrew the score. Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk25 was at the same time in production both in Leningrad and Moscow, where audiences were steady. Stalin attended a 1936 performance in Moscow. Immediately afterwards, an article appeared in Pravda, rumored to have been written by Stalin himself, under the title “Muddle Instead of Music.”26 As well as exemplifying “aesthetic formalism,” Lady Macbeth, according to the editorial, was “spasmodic,” “convulsive,” and a “petit-bourgeois distortion.” Shostakovich told Solomon Volkov in an interview that “meetings were organized to drum the ‘muddle’ into everyone’s head”; he added that “it went on as if in a nightmare [and] everyone turned away from me.”27 The security police had recently arrested and shot Shostakovich’s longtime friend and sometime intercessor Marshal of the Red Army Mikhail Tukhachevsky. Shostakovich himself expected arrest at any time and took to sleeping in the stairwell of his apartment building with his basic articles in an overnight bag so as to minimize the ordeal for his family when fate inevitably descended.

Solomon Moiseyevich Volkov, Russian musicologist and journalist (b. 1944)

Instead of sending the Black Maria to haul Shostakovich away, the dictator made it known that the nation’s most illustrious composer should take heed of “just criticism”; he should act to redeem himself. The Fifth Symphony nominally constituted that act – but it was not, in fact, a craven instance of kowtowing to the Oriental Despot. The Fifth became the first of Shostakovich’s “dual” works, incorporating superficial features to please the regime while being encoded (that seems the only useful word) with signs and gestures that sympathizers would recognize as dissident. Shostakovich made the most brazen – and to this day the least understood – of these gestures in the Finale.28 Under Socialist Realism, art, including music, must be optimistic. The typical Soviet symphony thus found an inevitable and stereotypical consummation in a brassy, rhythm-driven movement in the major-key on the pattern audible, for example, in Vano Muradeli’s hackneyed First Symphony (1938).29 The Finale of the Fifth cleverly parodies the formulaic gesture. That Finale is, in fact, a musical representation of anti-transcendence although Shostakovich used no such word in divulging its secret. Shostakovich told Volkov, “I never thought about exultant finales.” He explained that: “The rejoicing is forced, created under duress… It’s as if someone were beating you with a stick and saying, ‘Your business is rejoicing, your business is rejoicing,’ and you rise, shaky, and go marching off, muttering, ‘Our business is rejoicing, our business is rejoicing’.”30

Shostakovich characterized the Fifth as “irreparable tragedy.”31 The regime, as he expected, heard only what it wanted to hear, the adulation of its supremacy, with plenty of trumpets and drums. The state thought its prodigal rehabilitated; but as the abortive Sixth Symphony indicates, Shostakovich remained shaken, and yet at the same time his outrage was growing. Then came 22 June 1941 – the catastrophe of the German invasion and with it sudden new demands for artists to serve of the cause of socialism. When the Seventh Symphony, bearing the subtitle “Leningrad,” had its premier in Kuibyshev on 5 March 1942, it became an international sensation. Stalin arranged for microfilms of the score to travel by air sea and land to major orchestras in the West, where such luminaries as Arturo Toscanini,32 Leopold Stokowski,33 and William Steinberg immediately played it in concert and recorded it. The context of the war induced people to accept the Soviet explanation of the Seventh as embodying the determination of the proletariat to resist fascist aggression. All the formulaic gestures of musical Socialist Realism were present in the score, which Shostakovich had composed as a symphonic epos. The Bolero-like second subject proper of the opening Allegretto, with its long-drawn dynamic crescendo, befell ideological auditors as particularly exciting.34 What could this be but the symphonic depiction of the Wehrmacht as it crossed the Union’s borders and began to make a pincers around Leningrad?

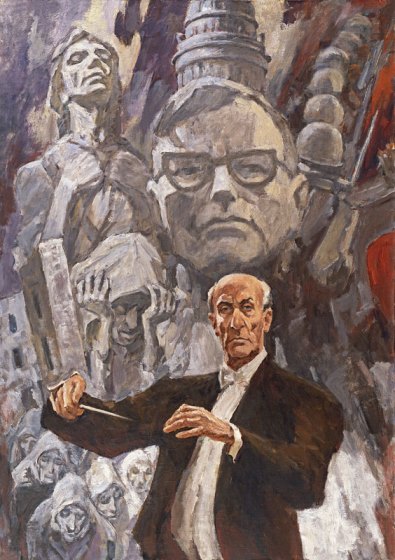

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

The Soviet misreading of Shostakovich’s new symphony worked itself out by an internal, almost Pavlovian logic. To borrow Berdyaev’s term there was no coherent speculative system in place among the governing deculturated elites that would permit them to cognize the symphony, once Shostakovich’s cannily placed stimuli had triggered their collective nod. A good deal more disturbing is the Western reaction to the Seventh. In its way, this Western response was and remains even more anti-transcendent than its Soviet counterpart. Writing in The Herald Tribune (15 October 1942), Virgil Thomson judged that the Seventh was “apparently designed for easy listening, perhaps even with the thought to making it possible for the radio listener to miss some of the repetitions without losing anything essential.”35 One wonders to what exactly Thomson was attending. In Music and Musical Life in Soviet Russia, Schwarz, while not fully endorsing the “critical consensus” that he cites, nevertheless opines that the Seventh “overstates and overtalks.”36 More recently, the arch-modernist composer-conductor, and lifetime French Communist Party member, Pierre Boulez, was quoted, in the BBC Music Magazine, as saying about Shostakovich, he “plays with clichés,” so that the music is “like olive oil, when you have a second and even third pressing, and I think of Shostakovich as the second, or even third, pressing of Mahler.”37 As the Seventh has been called a Mahlerian symphony, and not without justification, the late Mr. Boulez’s words may be taken as applying to it.

If the Seventh Symphony were not the colossus of all Soviet “war symphonies,” and if it were not the cheap article that artistically avant-garde commentary avers, what would it be? In Testimony, Shostakovich tells Volkov that “the Seventh Symphony had been planned before the war and consequently it cannot be seen as a reaction to Hitler’s attack.”38 Whereas “I feel eternal pain for those who were killed by Hitler,” Shostakovich says, “I feel no less pain for those killed on Stalin’s order.”39 Indeed, Shostakovich imagined his score in the beginning as an orchestral-choral elegy to Stalin’s victims with a religious meaning like Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms (1930).40 Circumstances would not permit so forthright an approach. When the concept of the Seventh became purely instrumental, eschewing the verbal specificity of setting a text; then, as Volkov puts it in Shostakovich and Stalin, “the religious content of the Seventh went into the subtext, but continued to reverberate.”41 In Testimony, Shostakovich comes straight to the point: “If the Psalms were read before every performance of the Seventh, there might be fewer stupid things written about it.”42 The composer also tells Volkov how, “even before the war, in Leningrad there probably wasn’t a single family who hadn’t lost someone.”43 In The Magical Chorus, Volkov writes, “Russian audiences were extremely sensitive to [the Seventh’s] religious overtones and they wept at every performance in the Soviet Union”; he adds, “In the difficult war-years Shostakovich’s music had a cathartic effect, and the concert hall substituted for the church, proscribed in socialist life.”44

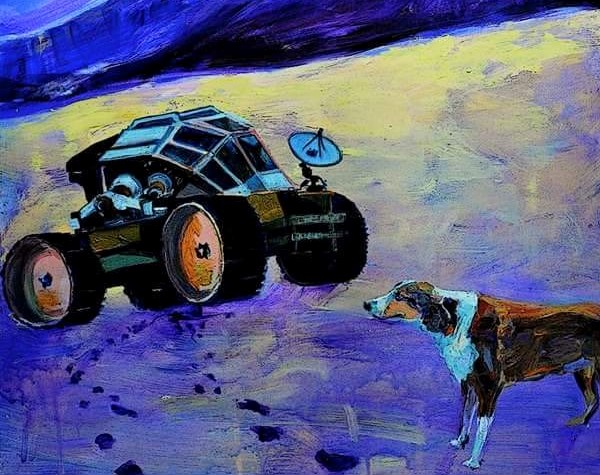

Lev Russov, “The Leningrad Symphony. Conducted by Yevgeny Mravinsky” (1980)

In light of these remarks it becomes possible to suggest the significance of some specifically musical details of the score. For example, the Seventh declares itself to be in the key of C-Major, but much of the work is in related – sometimes distantly related – minor keys that make evident its tragic rather than its propagandistic character. The composer’s insistence on minor-key harmonies disquiets the listener for most of the Seventh’s eighty-minute duration, making inexplicable Hugh Ottaway’s description of the work in BBC Music Guides: Shostakovich Symphonies as “one of the happiest of works,” animated by an “underlying joy [and] peace of mind.”45 (Again – to what was the man listening?) The Seventh’s opening “Leningrad” theme, while buoyant and upward-climbing, is nevertheless conditioned by gestures that choke or oppress its wont to ascend and develop. The theme is angular and a strident, resembling the sharp-edged, aggressive material that led Soviet musicology to condemn the Fourth Symphony46 and Lady Macbeth as “formalist.” Disparaging critics of the Seventh point to the non-developmental character of the Bolero-like second subject which begins quietly after what could be called the chastening of the first subject and its stricken subsidence into fragmented motifs. Non-development is precisely the point. The tune is deliberately idiotic, but it steadily gathers idiotic strength and ferocity. If the Finale of the Fifth were a representation of a subject being beaten with a stick, then this clownish march (it invites the label Djugashvili theme) would be the representation of the subject’s assailant.

The two middle movements of the Seventh – Moderato (Poco Allegretto) and Adagio – have elicited less commentary than the two outer movements. The Moderato is a scherzo-substitute, in which a slightly waltz-like motif reminiscent of Alexander Glazunov’s pre-revolutionary Valses de concert carries on quietly and uncertainly until a brash, martial cortege (Djugashvili theme II) tramples it brutally. The Adagio furnishes the Seventh with its apocalyptic core: The opening dirge for the strings alone is the self-evident vindication of Shostakovich’s own reference to the Psalms as the idea behind the symphony and to Volkov’s insistence that the symphony is a religious work – an instrumental Requiem for victims. This Adagio is a searing catharsis, genuinely tragic, calling to mind Psalm 130, “Out of the depths have I cried unto thee, O Lord.”47 The Finale (Allegro non Troppo) begins in low growling in the wind section, proceeds quasi una passacaglia, to become the Resurrexit of the implied liturgy with the return – not in triumph, but in spiritual certainty tempered by its ordeal – of the first theme of the first movement. Various critical pronouncements notwithstanding, Shostakovich’s score is remarkable for its prodigious use of a small number of basic musical motives, which continuously generate new thematic material in every movement. Audiences responded – and continue to respond – to the pattern of meanings to which the network of thematic cross-references in Shostakovich’s ingenious composition gives rise.

Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin (1872-1915)

“It is absurd,” writes Berdyaev in The Fate of Man in the Modern World (1935), “to think that the whole popular mass in Russia is penetrated by Marxian theory.”48 While it is the case, as Berdyaev writes, that “the modern dictatorship of ideas is based on the assumption that the spiritual life may be dealt with on exactly the same basis as the material life,” the spirit is nevertheless not a mere “epiphenomenon”,49 or what Marxists call a “superstructure.” In the contemporary world, the whole popular mass is not penetrated by Liberalism, the latest form of materialism; but the popular mass has been deprived of alternatives to the jejune Liberal Weltanschauung, which reduces everything to a material accident. It is spiritually disoriented. When, as Berdyaev writes, the regime refuses to acknowledge anything beyond “race, nation, sex… money, class, social grouping, [or] party,” the beleaguered masses lose their “spiritual resistance to suggestion and possession.”50 On the one hand there is the crowd and on the other there is – communion. What are the agencies of contemporary “possession”? Any reader of the Sydney Traditionalist Forum can supply his own list. Soviet masters could vainly order transcendence in endeavors like the Fourth Symphony (1986) of Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov (born 1936) or Alexander Nemtin’s “completion” of Scriabin’s Mysterium (1996).51 No one today has heard of, much less heard, these works. Would an accomplishment like Shostakovich’s Seventh or “Leningrad” Symphony be possible today? It seems vanishingly unlikely, but I remain open to refutation, please.

– Thomas F. Bertonneau is an American intellectual and professor. He has taught at a variety of institutions, and has been a member of the English Faculty at State University of New York, Oswego, since 2001. His articles and essays have appeared in a diverse array of scholarly journals including William Carlos Williams Review, Wallace Stevens Journal, Studies in American Jewish Literature, North Dakota Quarterly, Michigan Academician, Paroles Gelées: UCLA French Studies, and Profils Americains. He was a major contributor to the English section of The Brussels Journal. More recently, his work has appeared in The University Bookman, the John William Pope Center for Higher Education Policy as well as the websites The People of Shambhala and The Orthosphere. Thomas Bertonneau’s contribution to last year’s Symposium (“quo vadis conservatism, or do traditionalists have a place in the current party political system?”) was titled “Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs on Baudelairean Traditionalism”.

– Thomas F. Bertonneau is an American intellectual and professor. He has taught at a variety of institutions, and has been a member of the English Faculty at State University of New York, Oswego, since 2001. His articles and essays have appeared in a diverse array of scholarly journals including William Carlos Williams Review, Wallace Stevens Journal, Studies in American Jewish Literature, North Dakota Quarterly, Michigan Academician, Paroles Gelées: UCLA French Studies, and Profils Americains. He was a major contributor to the English section of The Brussels Journal. More recently, his work has appeared in The University Bookman, the John William Pope Center for Higher Education Policy as well as the websites The People of Shambhala and The Orthosphere. Thomas Bertonneau’s contribution to last year’s Symposium (“quo vadis conservatism, or do traditionalists have a place in the current party political system?”) was titled “Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs on Baudelairean Traditionalism”.

Endnotes:

- Thomas F. Bertonneau, “Before Camus: Gustave le Bon on ‘The World in Revolt’” The Brussels Journal (online) (14 January 2010 @ 9:40 WET) <brusselsjournal.com> (accessed 21 February 2016).

- Gustave le Bon, The Crowd (New York, Dover: 2002 [1896]).

- Ibid. at p. 24.

- Thomas F. Bertonneau, “Nicolas Bardyaev And Modern Anti-Modernism’” The Brussels Journal (online) (12 July 2011 @ 12:56 WET) <brusselsjournal.com> (accessed 21 February 2016).

- Nicolas Berdyaev, Freedom and the Spirit (Semantron Press, 2009 [1927]).

- Ibid. at p. 249.

- Ibid.

- Nicolas Berdyaev, The Meaning of the Creative Act (Semantron Press, 2009 [1916]).

- Ibid. at p. 205.

- Ibid. at p. 292.

- Ibid. at p. 238.

- Ibid. at p. 292.

- I. Stetsky, Manager of the Culture and Leninist Propaganda Section of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, “Under the flag of the Soviets, Under the Flag of Socialism”, Address to the Soviet Writers’ Congress 1934, reprinted in Maxim Gorky et alii, Soviet Writers’ Congress 1934: The Debate on Socialist Realism and Modernism (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1977); the writer relies on the online version transcribed by Jose Braz for the Marxist Internet Archive (2004) <marxists.org> (accessed 21 February 2016).

- Boris Schwarz, Music and Musical Life in Soviet Russia 1917-1970 (New York: W W Norton, 1973).

- Ibid. at p. 115.

- Ibid. at p. 114.

- Ibid. at p. 106.

- Ibid. at p. 124.

- The writer recommends the Composer’s Symphony No 5 in D minor, Op 47, by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra, Conducted by Evgeny Mravinsky (1983).

- Igor Stravinsky, Poetics of Music in the Form of Six Lessons Arthur Knodel and Ingolf Dahl (transs.), (Harvard University Press, 2003 [1942]) p. 115.

- Ibid.

- See Symphony No 7 in C major, Op 60, by the Mariinsky Theatre Symphony Orchestra, Conducted by Valery Gergiev (date unknown).

- See Symphony No 6, by the Wiener Philarmoniker, Conducted by Leonard Bernstein (date unknown).

- See Symphony No 4 in C minor Op 43, by the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, Conducted by Vasily Petrenko (date unknown).

- See Ignat Solzhenitsyn, Mariinsky Opera, St. Petersburg (11 February 2014).

- “Muddle Instead of Music” Pravda (26 January 1936); the writer relies on the online version of the same title at the Arnold Schalks Internet Archief (undated).

- Solomon Volkov, Testimony: Memoirs of Dimitri Shostakovich Antonia W. Bouis (trans.) (New York: Harper and Row, 1979) [orig.: Свидетельство] p. 114.

- See Symphony No 5 in D minor Op 47 (Finale) by the State Symphony Orchestra of the USSR, Conducted by Evgeny Svetlanov (date unknown).

- See Symphony No 1 in B minor (“To the Memory of Sergei Mironovich Kirov”), Conducted by Konstantin Ivanov (1938).

- Citata Solomon Volkov op. cit. at p. 183.

- Ibid.

- See Symphony No 7 in D major, Op 60 (“Leningrad”), by the NBC Symphony Orchestra, Conducted by Arturo Toscanini (19 July 1941).

- See Symphony No 7 in D major, Op 60 (“Leningrad”), by the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, Conducted by Leopold Stokowski (1944).

- See Symphony No 7 In C, Op 60, (“Leningrad”), by the WDR Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra, Conducted by Rudolf Barshai (date unknown).

- Citata Laurel E. Fay (ed.), Shostakovich and His World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004) pp. 91-92.

- Boris Schwarz op. cit. p. 191.

- Citata Rosie Pentreath, “11 Important Shostakovich Quotes” Classical-Music.com (online) (25 September 2014) <classical-music.com> (accessed 21 February 2016) at § 10.

- Citata Solomon Volkov op. cit. (1979) at p. 155.

- Ibid.

- See Symphony of Psalms, by theMilwaukee Symphony Orchestra with the Wisconsin Conservatory Symphony Chorus, Conducted by Lukas Foss (date unknown).

- Solomon Volkov, Shostakovich and Stalin Antonia W. Bouis (trans.) (Alfred A. Knopf, 2004) p. 175.

- Citata Solomon Volkov op. cit. (1979) at p. 181.

- Ibid. p. 135.

- Solomon Volkov, The Magical Chorus – A History of Russian Culture from Tolstoy to Solzhenitsyn Antonia W. Bouis (trans.) (Vintage, 2008) p. 141.

- Hugh Ottaway, BBC Music Guides – Shostakovich Symphonies (Washington: University of Washington Press, 1978) p. 34.

- See Symphony No 4 in C Minor Op 43, by the USSR Ministry of Culture Symphony Orchestra, Conducted by Gennady Rozhdestvensky (circa September 1935 – May 1936).

- The writer relies on the New International Version.

- Nicolas Berdyaev, The Fate of Man in the Modern World Donald A. Lowrie (trans.), (Semantron Press, 2009 [1935]) p. 59.

- Ibid. p. 60.

- Ibid. p. 127.

- See Alexander Scriabin and Alexander Nemtin, Mysterium (Preparation to the Final Mystery), by the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin and the St Petersburg Chamber Choir, Conducted by Vladimir Ashkenazy (date unknown).

Citation Style:

This article is to be cited according to the following convention:

Thomas F. Bertonneau, “Shostakovich’s ‘Leningrad’ Symphony: Art Transcending Politics” SydneyTrads – Weblog of the Sydney Traditionalist Forum (30 April 2016) <sydneytrads.com/2016/04/30/2016-symposium-thomas-bertonneau> (accessed [date]).

Leave a comment